Canadian Broadcast Hall of Fame

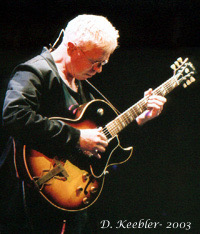

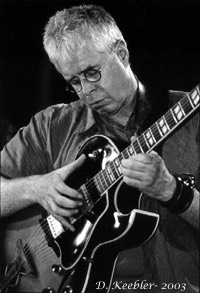

D. Keebler

Posted December 6, 2004

Bruce was asked to perform at this year's Canadian Association of Broadcasters Convention, held in Ottawa. He played a couple of songs in the Confederation Ballroom, located in the Westin Hotel. Among the inductees was Oscar Peterson. Bruce was inducted into the CAB in October, 2002.

Remastered CDs

From True North Records

Posted November 10, 2004

True North informed me that the next three remastered CDs from Rounder are:

- Sunwheel Dance: Bonus tracks will be Morning Hymn and a solo version of My Lady and My Lord. Morning Hymn was previously available on 45rmp as the flip side of It’s Going Down Slow (TN4-109).

- Circles In The Stream: No bonus tracks in part due to time limitations for a single CD.

- Big Circumstance: Bonus track is an acoustic version of If A Tree Falls, with Steve Lucas on bass. This version was recorded circa 1993.

While the release date is tentative, March 2005 is the current estimation.

The Ithaca Journal

Ithaca, New York

October 28, 2004

Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn returns to the State Theatre

By Heather Dunbar

Special to the Journal

The Friday Bruce Cockburn solo concert at the State Theatre in Ithaca is not so much an album tour as a career continuity.

In a recent conversation with the artist, I realized these collections are never even a biannual affairs and that this steady approach serves and suits Cockburn (pronounced “Co-burn”) well. He wrote the songs for the 2003 release, “You’ve Never Seen Everything” between 1999 and 2002 (with a 2001 re-write from 1978). He has another half of an album written, which will eventually be commercially released on the True North label in a year...or two.

The collection showcases 12 well-written songs, played and crafted, with art, heart, talent, honed with practice, from an above-our-northern-border point of view and themes, the same as ever in this substantial 30-year career. There’s hard-edged social commentary, refreshingly free of didacticism, and directivity, similar in tone to Cockburn’s very first and very direct protest song “Going Down Slow” from the early album, “Sunwheel Dance,” in a range toward the incendiary volatility of his hit “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.” Counted among the politically bent selections are: “All Our Dark Tomorrows,” “Trickle Down” and the title cut.

There are also more poetic and painterly, open-agenda-ed political works, as one might expect of an artist of such a depth, exemplified in “Don’t Forget About Delight.” There are gorgeous, mature, complex love songs - “Everywhere Dance,” “Put It In Your Heart” and “Wait No More.” You find artistic introspection, full of feeling and self-acceptance in the lead song “Tried and Tested” and “Open.”

There are a number unusual and even unique topical and stylistic points of focus on “You’ve Never Seen Everything.” The recording is distinguished by the inclusion of some acoustically realized, fresh sounds derived from the electronica realm. Some of the songs you can dance to, others are ballads or almost spoken word to music, not sung. If you favor old, acoustic Bruce Cockburn, with hope worn on his sleeve, the closing song, “Messenger Wind” may well be redemptive.

A range of influences

Cockburn explains his crisp, decisive and lovely guitar playing: “A failed attempt to imitate various things have led to the style I play in. Everything from Scotty Moore, who played with Elvis, to the old blues guys -- Bill Broonzy, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lightning Hopkins -- to the jazz guitarists of the 60’s: Wes Montgomery and others.

“I dabbled at all of those things and never got any of them right, but somehow added them all together, which amounted to something different.”

He has also listened to, incorporated and attributes “the entire Folkways catalog,” elements of Japanese music, Tibetan music and music from Guadalcanal and all and parts of Africa to his playing. He attended Berklee School of Music for a time and studied jazz and world music styles.

The strongly personal, and to my ears, especially beautiful and unique Christian art songs of the beginning third of his career are no longer Cockburn’s style. These spiritual values are now submerged and suffused into his songs. Christianity and Judaism as well as Sufism and Hinduism have influenced his spiritual outlook and practice. As a result, spirituality and emotion, especially sadness, frame a range of subjects: God, global economics, hope in the face of tragedy and malevolence -- all there in the perspective of right now and also eternity.

When you take pause to listen to the words of his reggae-influenced 1979 hit, “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” is a declaration of freedom from the fear of death.

“Spirituality is at the center of existence and touches everything...and shows up in everything,” says Cockburn.

Canadian roots

Cockburn moved from Ottawa to Toronto, Ontario, in 1980. Last week he called from Montreal, but he very seldom sings and no longer records songs in French. You do find translations of each song into poetical French in the liner notes, along side the sung English version.

Cockburn explains the letting go of the French repertoire: “I sort of stopped liking those songs a long time ago -- they’re too representative of a particular time and place and state of mind and it just didn’t feel good to sing [them]. I’m doing a bunch of shows in Quebec right now and did re-learn a version of [a French song] from a live album from the mid 70’s. I sang it a bunch of nights and I just didn’t like it. People here don’t seem to miss it.”

Like fellow Canadian Gordon Lightfoot, Cockburn made the choice to buck the trend in the 60’s to start his career in his native country first before touring Europe and Japan rather than launching in the United State as did Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young and many others. (Later expatriates included Jane Siberry and chanteuse, k.d. lang who honored Cockburn by inclusion a rendition of his “One Day I Walked” in her recent collection of anthemic renditions of great songs by Canadians: “Hymns of the 49th Parallel.”)

Who of other Canadians would Cockburn pay to see these days, given he does not follow other singer-songwriters much? Alanis Morrisette, for one. He also mentioned he favors electronica artists from Ninjatunes Records in Montreal, such as Eamonn Tobin and others. Cockburn gave a heads up to watch out for people with whom he would personally enjoy collaborating: trumpeter Dave Douglas and a great, young female New York City-based guitar instrumentalist, Kaki King.

Political inclinations

The fact of his being a Canadian brings a lot to bear on Cockburn’s art, politics and way of being. As a social activist on the international issue of land mines has helped shape his sense of who he is and what can and should be pursued and the means to do so.

When asked, Cockburn explained that the difference between being from Canada versus the United States is that in Canada the early-voiced divergence between the Quebequois and Anglo-Canadian populations has led to a pulling together of their country, a commitment to consensus, an aversion to adversarial politics and created surplus energy to focus outward on the rest of the world with equanimity -- in strong contrast to the U.S. political tradition of majority rule.

When asked what one thing Cockburn might want U.S. people to consider in the upcoming election, he doesn’t mince words. “They just need to vote,” he says. “Doesn’t matter what they know about me. They just need to vote that f----- out of there. The world is waiting for that to happen. I don’t know that it will, but that is what we’re all rooting for outside the U.S.”

Bruce Cockburn performs Friday at the State Theatre. Tickets for the 8 p.m. show are $25 and $28 and are available at the Clinton House Ticket Center, by calling 273-4497, online at www.statetheatreofithaca.com, and at the door.

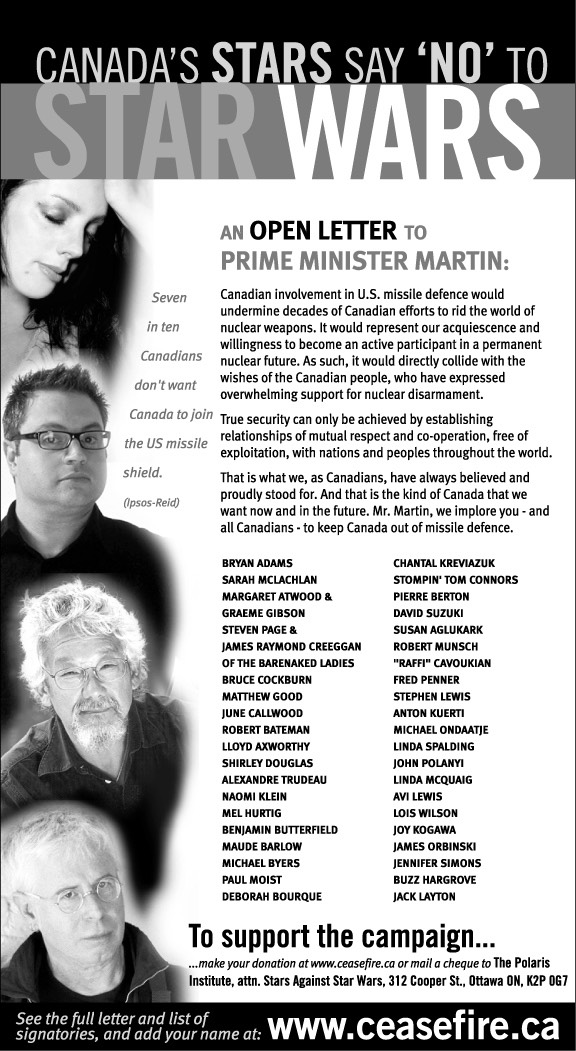

Posted October 22, 2004: An ad that Bruce and many others helped pay for that's running in several papers across Canada including today's Toronto Star.

On the Road with Bruce Cockburn/ Michael Geisterfer

Posted September 9, 2004

Mike Geisterfer went on the road with Bruce Cockburn for three concert dates in 2003: July 31, Eugene, Oregon; August 1, Portland, Oregon; August 2, Seattle, Washington. Mike was on assignment for Reader's Digest Canada at the time. New management at the top of the magazine, not getting the value of the subject matter, bumped the story at the last minute. Because Mike had such a unique opportunity in writing this story it would have been a loss for it not to be published in some fashion. With Mike's permission, here is his account of four days with Bruce Cockburn. My BIG thanks. This article may not be reprinted without the author's written consent. -Daniel Keebler

Pinning Canadian music icon Bruce Cockburn down for an interview is like trying to have a conversation with someone through the open window of a bus as it whizzes by on the highway. It works a lot better if you are actually on the bus with him, which is precisely what I proposed to his lifelong manager, Bernie Finkelstein in Toronto.

Pinning Canadian music icon Bruce Cockburn down for an interview is like trying to have a conversation with someone through the open window of a bus as it whizzes by on the highway. It works a lot better if you are actually on the bus with him, which is precisely what I proposed to his lifelong manager, Bernie Finkelstein in Toronto.

“Go on tour with him?” Finkelstein laughed. “He’s never allowed any journalist to do that before,” he said “I doubt he’ll go for it.”

The proverbial rolling stone, Cockburn is notoriously cagey with the media, and even worse when ambushed by a journalist. I’ve seen him in action. He gets a panicked look in his eyes, like a wild animal pacing its cage, and his answers are curt and prickly like he really hates being in the public glare.

“Bruce is an intensely private person,” said Finkelstein. “He doesn’t even talk to me about his personal life.”

A few months later, long after I’d given up on the idea, I received a phone call from Bernie. “Meet him in at the Hilton in Eugene, Oregon next Thursday,” he said. “You can stay with him until Seattle two concert stops further.”

Scrambling to arrange my flights from Ottawa, I had a twinge of anxiety. What if I went all of the way to Oregon and he refused to talk to me? What if I asked the wrong question and he kicked me off the bus? Flying over the wheat fields of Eugene a week later, my stomach was in knots. Apart from the single phone call from Bernie, there had been no confirmation. I had no idea how I would even find Cockburn once I arrived there.

Inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 2001, Cockburn garnered international acclaim back in 1979 when his catchy hit “Wondering Where the Lions Are” broke through Billboard’s Top 25 in the U.S. Playing to packed houses not only in North America but also around the world, the intrepid folksinger became one of Canada’s most recognizable and controversial traveling minstrels, mixing politics and religion in a rich tapestry of music.

“Bruce Cockburn's career is like a decades-long quest to make sense of the beauties and the brutalities of the world,” says U.S. rock journalist Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers, author of Rock Troubadours and The Complete Singer-Songwriter. “Finding words and music that express his thoughts and observations along the way has led him to explore many styles of music from around the world -rock to reggae, jazz to folk to electronica - but it all seems of a piece. Cockburn is a real troubadour in the traditional sense, traveling and sharing poetry and news.”

Now I had to find him in some bustling U.S. coastal town in Oregon. Hopping into a cab at the airport, I told the young driver of my predicament: I needed to meet a Canadian musician at the Hilton, and how I wasn’t even sure he’d be there.

“What’s his name?” he asked.

“Bruce Cockburn.”

“Don’t worry. He’s there.”

My jaw dropped. “You know who Bruce Cockburn is?”

The driver nodded his head. “Everybody around here knows Bruce.” I didn’t believe him. Cockburn is probably Canada’s most elusive icon. You hardly know he’s around until he comes to town on one of his perennial tours, and even then there is little fanfare. No media blitzes. No mega-concerts. Just a quiet announcement of his coming, and then an equally discreet departure, often in the middle of the night as it turns out.

I really doubted that many in the U.S. had ever heard of him and that this cab driver was just a fluke. I was wrong on both counts. Bruce Cockburn was at the Hilton. In fact he was standing right in front of his dark green tour bus as we wheeled into the main entranceway.

Clad in biking shorts and a bright yellow nylon pullover with matching helmet, he was straddling a gray mountain bike and talking to one of his crew members. At 58, he was a silver-haired man with a gold earring in his left ear and round wire-rimmed glasses on his nose, the same style he has worn since his career began over thirty years ago. I vaulted out of the cab and introduced myself.

“I’m Bruce,” Cockburn said, eyeing me coolly. “We’ve been expecting you. This is Leslie, my road manager. He’ll show you where to put your stuff. I’ll see you at the venue.” With that, he turned and rode off on his bicycle.

Leslie Charbon is a thin dark-haired man who, on this blistering hot summer day, was dressed in a tee shirt and shorts. “This is our home,” he said, leading me into the tour bus. With wrap-around cushioned seats, a kitchenette, bathroom, ten bunks and private quarters in the back it is luxurious but cramped, housing Cockburn, his nine-member crew and now me. The bus lurched forward just as I set my bags down and we eased into the early afternoon traffic.

“The routine is simple,” Leslie told me. “We usually leave the hotel around noon and go straight to the venue. Set-up is from 1-3, then a sound check at 5 p.m., dinner at 6 and then the concert at 8 p.m.” After the concert the crew packs everything back into the tag-along trailer and the bus sets off for the next stop of the tour, often traveling until three or four in the morning.

Cockburn gives about 200 concerts a year in a dozen different countries. This past year alone he has traveled through all of Europe including the British Isles, Australia and even made a quick foray into war-torn Iraq where he met with medical officials, religious leaders and children in a cancer ward in Baghdad. His peripatetic itinerary is often grist for the mill. He’ll release viscerally stunning albums after visiting global flashpoints like Guatemala or Cambodia, his social passion stoked by the cruel images he witnesses.

Born in Ottawa, Ontario, on May 27, 1945, he grew up in the Ottawa Valley and attended Nepean High school where his 1964 yearbook photo reveals a brooding teenager with a fitting epitaph, “Waiting quickly.” The caption reads: “Bruce sang in the choir and hopes to become a musician. He has a guitar. His pet peeves include phoney people and advertising.”

This latter peeve may help explain why superstardom has always eluded him. In spite of 27 albums and a sizzling 30-year career, Cockburn remains a bit of an international enigma, his career path seemingly hampered by poor marketing and lacklustre distribution. As recognizable an icon in Canada as his counterpart, Bob Dylan is in the U.S., Cockburn has nevertheless failed to break into the North American market in any spectacular way. Part of the reason may be that he was never really hungry for that kind of success.

“I would have been happy to make my living playing on the streets if that’s what it took for me to support myself,” he told me. At one point early in his career, that is precisely what he did.

Strapping his aunt’s guitar to his back in the early 1960’s, Cockburn busked for francs on the streets of Paris, spending at least one night in jail for performing without a licence. He returned to North America in 1966 and after a brief stint studying theory at Boston’s Berklee School of Music, he set up musical shop with The Children, a local Ottawa band. In 1969 he went out on his own, embarking on a richly textured spiritual odyssey that would take him around the world numerous times and find him standing alone on a hot July afternoon, outside the Macdonald Theatre in downtown Eugene, waiting for his guitars to be unloaded from the back of the tag-along trailer.

Unsure as to what the rules of engagement were, I stood a few feet away and waited for him to make the first move. Only, he never did.

I watched expectantly as he chatted amiably with members of the band and crew as they set up, then with chagrin as he walked by, ignoring me completely. After two hours I was convinced that all I had suspected of him was true: he was aloof, unapproachable, even a little arrogant in his attitude towards members of the media.

Confused as to why he had agreed to invite me on tour with him, I decided that come hell or high water, I would have to make the first move. My opportunity came when he suddenly announced that he was going to go and pick up a new guitar that he had bought just a day earlier.

“Mind if I join you?” I ask.

“Not at all,” he replied. “I could use the company.” We strolled out of the backstage door and were immediately accosted by a young man who had been waiting for hours in the hot sun for precisely this eventuality.

“Would you autograph these?” he asks, thrusting a leather-bound binder of CD covers into Cockburn’s reluctant hands.

“Sure,” Cockburn said, removing one of the black leather gloves he wears almost constantly to protect what are probably the most valuable tools of his trade: his guitar-picking fingers. Within minutes we were on our way again and engaged in an animated conversation. Suddenly the young fan passed us on his bicycle and nearly crashed into the back of a parked car, an adoring gaze firmly fixed on Cockburn.

“He really likes you,” I said.

Cockburn just nodded his head, as if all of this were routine. I had my doubts until a few minutes later when yet another young man suddenly came bounding towards us from across the street.

“I thought it was you,” he said, dancing a backwards jig in front of us. “I’m sorry to interrupt but I just had to say hello. You’re my hero. I have all of your CDs. I think you are great.”

Then he turned to me. “You’re probably great too, but I don’t know who you are.” I was shocked. If this had been Moosejaw or Halifax I would have been less surprised. But downtown America? How did anyone here know who he was?

“Bruce Cockburn is probably Canada’s best-kept secret,” said Doug McClary, another Eugene resident and faithful follower of Cockburn whose own children have now become avid fans. “He has a thoughtful spirituality and intelligent lyrics that come straight from the heart.”

As we walked into the McKenzie River Music store on 11th Avenue a few minutes later there was an immediate tingle in the air. About seven people were milling about –customers and sales staff- and they all stopped what they were doing and slowly made their way towards the front. They didn’t crowd him, or pepper him with questions but rather orbited around him in reverential silence as he completed the transaction for his new guitar.

milling about –customers and sales staff- and they all stopped what they were doing and slowly made their way towards the front. They didn’t crowd him, or pepper him with questions but rather orbited around him in reverential silence as he completed the transaction for his new guitar.

From the expressions on their faces it was clear that this was an event that would be seared in their memories, a story that would be told to their grandchildren. Bruce Cockburn walking into that tiny guitar shop would be like Wayne Gretzky stopping by to play a game of pickup hockey at a small-town arena, or the Pope dropping in to conduct a mass at a local parish church. For hundreds of thousands of people throughout North America and the world, Bruce Cockburn is not just an accomplished musician. He is a legend that is larger than life.

Any doubts I may have had about this were erased as we were about to leave, when cameras began to appear as if from thin air, and the small throng clamoured for his autograph. He acquiesced with respectful gentility. There was not a hint of arrogance in his attitude, no sense that he was any better than any one of them.

“This guitar is exactly like my first guitar, a 1961 Gibson ES 175,” he told me as we walked out the door. “It cost me $250 back then.” He didn’t tell me how much he paid for this one, but I managed to peek at his VISA slip as he signed it. It set him back a cool $5200 in U.S. currency, and it is just one of over a dozen guitars that he owns.

“I started getting interested in guitars at about the age of 14,” he said “Of course that was back in the 1950s when guitars went with leather jackets and drugs and sex. My parents said that if you promise not to buy a leather jacket and do any of those other things then you can take guitar lessons. So I promised them and then proceeded to break all of those promises.”

After dabbling in rock and roll with The Children in the late 1960s, Cockburn’s tastes turned to the acoustic guitar. His first few albums were characteristically mellow and spiritual. He was an introverted mystic that sometimes seemed to get lost in the matrix of solo guitar music. In the late 70s and early 80s though, things began to change. An OXFAM-funded trip to Guatemala fuelled his moral outrage and the result was the politically charged missive, ‘If I had a Rocket Launcher.’

From that point on, he was more than just another musician making the rounds. In the minds of critics and fans alike he became an angry prophet, a fiery preacher brandishing his own unique brand of doom and redemption through musical artistry and lyricism.

“I took to the guitar almost immediately,” he told me as we continued down the street in Eugene. “It became a refuge for me through my teenage years. I never really knew what I wanted to do with my music. I went to Berklee (College of Music in Boston) and then dropped out when I realized it wasn’t taking me in the direction I wanted to go.”

His candour and easy manner surprised me. Of course I had been treading lightly, lobbing softball questions for fear he would kick me off the tour even before I got started. Still, there was not a hint of the prickliness I had been expecting.

Crowds began trickling into the 750-seat theatre at 7 p.m. and in short shrift their throngs swelled to an unusually colourful torrent. Stepping into the lobby of the theatre on that particular night was like being whisked back to 1969 when beatniks and hippies roamed that part of the earth. Tie-dyed tee shirts over homespun gingham dresses proved to be the evening couture of choice, while barefoot diapered toddlers ran squealing down crowded aisles in a carnival atmosphere fairly bursting with anticipation.

With barely ten minutes remaining before the official start of the concert, I made my way backstage to the green room expecting to see the band engaging in some form of pre-performance ritual. There was no one there though, just Cockburn quietly playing scales on his new guitar. The others had not yet returned from dinner. Spying me, Cockburn quietly retreated to his dressing room and closed the door. Then he opened it again with an apologetic smile. “You’re one of the crew now,” he said. “Help yourself to some wine.”

He pointed to a table sagging under the weight of fruit, cheese, crackers, wine and an assortment of international beers, all compliments of the house. He closed the door and the sound of vocal arias drifted through the cracks. Over the years his voice has developed a rich timbre, catching up to the rest of his prodigious musical talent.

The others began drifting in a few minutes before the looming 8 p.m. deadline. “Aren’t you nervous?” I asked Julie Wolf, the Seattle-based keyboard player as she eased herself into a dusty green lounge chair.

“Not nervous,” she replied. “Excited perhaps. I like getting up there and playing for an appreciative audience.”

Apart from the lone American Wolf, the rest of the band members are all Canadian. Bass player Steve Lucas is a professorial, bespectacled man who has followed Cockburn on numerous tours throughout the world, including Japan. His percussion counterpart is a fresh-faced youngster from Etobicoke by the name of Ben Riley. The baby of the group, he began playing for Cockburn seven years earlier at the tender age of 19.

At 8 p.m. the band still showed no signs of moving. They were all lounging about, snacking on crackers and soda water, exuding nary a hint that anything out of the ordinary was in the offing. This may in fact have been the key to their apparent indifference: having followed this routine night after night so many times it is no longer extraordinary. “It is actually all quite routine and boring,” said road manager Leslie Charbon.

At ten minutes past the hour, he banged on Cockburn’s dressing room door and poked his head in. “Two minutes,” he yelled. Then he smiled at me. “I’m the only one who can do that,” he said.

A few seconds later the door opened and Cockburn strolled out dressed in a purple shirt and matching trousers. Flashlight in hand, Leslie led them up the back stairs to the curtained stage wings. The lights dimmed and a roar erupted from the cavernous auditorium where every seat was filled right to the rafters in the back.

With no introduction, Cockburn and his band walked onstage and the crowd screamed its delight.

“It took me a long time to get used to this sort of thing,” Cockburn later confessed. “The power of it scared me. I thought it might overwhelm me.”

Having attended numerous Cockburn concerts over the years, I had never seen an audience as engaged as this one. There was a frenzy of exuberant banter as he strapped on his guitar, then a wave of joy as the first pulsing strains of his new release, Tried and Tested, flowed from his guitar. With his latest album having just been released in the U.S. market, it is unlikely that many of them have even heard it before, yet they greeted the opening bars with such enthusiasm, it is clear that for them Cockburn can do no wrong.

Heads bobbing in unison, they became a single entity, their bodies arched forward as if to capture every rift, every harmony, every intricate poetic nuance. They love his music in whatever form it takes, and over the years it has taken many forms. He used to be considered one of Canada’s foremost acoustic folk musicians, capable of weaving complex arpeggios with equally elaborate strands of lyrical mysticism all through the hollow body of an unplugged guitar.

I remember watching with dismay as he picked up an electric guitar during a late 1970’s concert in London, Ontario and began tearing through a set of fiery jazz and rock rifts. This was not the cuddly folksinger that everyone had come to know and love, but a much angrier doppelganger. “From the beginning, Cockburn has been a musical traveler,” says American rock journalist Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers.

At a point in U.S. history where political protest is barely tolerated and often punished on the airwaves, Bruce Cockburn is a bit of an anomaly. He had barely picked out the opening notes of his angry 1984 breakout protest song, If I had a Rocket Launcher, before a roar of approval erupted from the audience. For many of them, Cockburn’s appeal is not just musical but political. Yet if he was tempted to preach between songs, it didn’t show.

The chorus of requests at the end of each song elicited nothing more than a woeful smile from Cockburn who has become adept over the years at ignoring pleas to hear his old familiar tunes. Some might argue that he is pretty good at ignoring his audiences completely. On this particular night, well into his third song he has not uttered a single word, and it was clear that his audience would have none of his coyness.

“What did you do today, Bruce?” one of them cried.

He laughed and shook his head in mock disbelief. “Not much,” he said. “Well actually, I did buy this new guitar.”

“What kind is it?”

“A 1961 Gibson, just like my first guitar.”

“Did you get a good deal?”

“No,” he laughed. “I think I paid more than I should have.”

“Hey Bruce,” someone else cried, “How’s Gord?”

“Gord?”

“Gordon Lightfoot.”

“Oh, well he’s been sick you know. But I think he’s doing better.”

And so it went. I have never seen this level of interaction in any Cockburn concert anywhere in Canada. It was becoming clear to me that just as he would not talk to me on our first meeting until I first reached out and talked to him, so too is he unlikely to engage his audience in any kind of conversation unless they start it. This dynamic seemed to work just fine among the gregarious and outgoing U.S. audiences, but I could see how it might be disastrous in shyer, more reserved venues, like those in Canada.

“Canadian audiences are a lot different than American audiences,” said Cockburn. “Basically they sit on their hands until the end of the concert. It can make you lose confidence. You start wondering if they actually like the music.”

Back in Eugene, it was clear that this was more than a concert. It felt more like an Irish kitchen ceiligh and that Cockburn had a personal relationship with each one of his audience members. In fact, at the concert in Portland the next night, someone cried out, “We love you, Bruce.”

His reply: “The feeling is mutual.”

If true, it is a strange sort of love. Whatever the appearance might be, there is an invisible line between performer and audience. Unless you have a backstage pass, you cross that line at your own peril. At all of the three concerts that I attended, security was extraordinarily tight. I would have to show my pass to at least three burly guards in order to gain access to the greenroom backstage, and even if an interloper did manage to get past the guards, they would still have to deal with Cockburn’s personal gatekeeper, Leslie Charbon.

I saw proof of this at the Seattle concert on Saturday night. Cockburn and the other band members were relaxing in the greenroom during intermission when a young woman carrying a large shoulder bag tentatively approached the plate glass patio door from the outside. Security normally so tight, everyone assumed that she had a backstage pass.

I was standing across the room, chatting with Leslie Charbon when suddenly he stopped talking, and his body tensed, like he was poised to dash off. His gaze was fixed intently on the young woman. As road manager it is his job to book hotel rooms, confirm venue sites and handle all of the logistics of keeping the band happy on the road. As personal bodyguard, it is his job to ensure that nothing happens to Cockburn.

The young woman popped her head through the door and thinking she was a friend of a band member Cockburn said, “Come in. Who are you looking for?”

Placing her bag on the table in front of him, she reached into it. “I wanted to give you a present,” she said, which is about when pandemonium broke loose. Bolting from his chair a few feet away, Leslie Charbon grabbed her around the waist and with lightning speech wrenched her out of Cockburn’s range.

“Get the hell out of here,” he screamed pushing her out of the emergency doors. Her ‘gift’ could have been anything: flowers, a notebook of homespun poetry, or a loaded gun.

“People become bitterly disappointed when I don’t turn out to be what they thought they were going to get,” said Cockburn wistfully. “Many people who have made overtures want to be friends have been crestfallen or worse when they weren’t reciprocated. I like the people but my life is what it is. I can’t accommodate everyone that wants to be part of it. If they really knew what it was to be part of it not as many of them would want to be.”

It is a bewildering but not uncommon irony among professional musicians that apparent intimacy with an audience is mirrored by profound loneliness in their personal lives. “I’m not in an intimate relationship at the moment,” Cockburn confided to me on the bus between Seattle and Vancouver. “I’ve been in several long-term ones, which haven’t lasted for various reasons.”

“How do you feel about that? Do you feel sad?”

“Well at the moment I do because I don’t have a partner and I get lonely. On the other hand, it has been over a year now since I split up with my last partner and I feel like I’ve learned a lot in that time. Being alone has been really instructive and helpful.

“This is the longest that I’ve been without female company. It is an opportunity to grow, at my age at this stage of my life I value that opportunity and I intend to make the most of it. Obviously if I am ever to get into another relationship, whatever it is I bring to these things that makes it not work, I want to fix so at least I know what I am dealing with in myself. Maybe it has a chance, maybe it doesn’t. If I’m meant to be with somebody they’ll show up. Right now they are not showing up and I’m not too worried about it.”

When he is not on the road, Cockburn lives alone in a rented house in Montreal. His only daughter lives in an apartment in the same building. She was born in 1975 when he was married to his first and only wife. They divorced a few years after his daughter’s birth.

The irony is that in fact women did show up, continually. They stood in eager packs at the backstage door after each concert, clutching pieces of paper, ticket stubs, birthday cards, anything for an excuse to get close enough to him for an autograph. Yet it is precisely this level of eagerness that makes Cockburn cringe, almost in fear.

At the backstage door in Portland, Cockburn cast a furtive glance through a crack in the door. “Are they still out there?” he asked, his eyes fixed on a particularly zealous pack of groupies.

When it was clear that they were not about to leave until they had at least caught a glimpse of him, Cockburn stoically opened the door and made his way to the bus. They all applauded as he approached, and he gave them an awkward smile.

By this time it was clear to me that he doesn’t avoid his fans out of arrogance or pride, but rather out of simple shyness. Cockburn is a classic introvert: complex, intense and pathologically incapable of engaging in small talk.

On that night in Portland he actually did go and speak with that small band of admirers and his demeanour was apologetic, as if he knew he couldn’t possibly meet their enormous expectations. Were it not for an extrovert among them the result could have been an awkward shuffling silence.

For all of his intensity, Cockburn seems to have mellowed with the years.

“One of the benefits of getting older is that you don’t get as bothered about stuff when you were young,” he said as we approached the outskirts of Vancouver. “You reserve your concern for the essentials.” He confessed that for a long time he struggled to enjoy the experience of playing in front of an audience. “I would come off-stage and little things would get to me a lot. Like if I blew a line here I would get all worked up about it.”

Finally his manager, Bernie Finkelstein came up to him and said: “It’s time you stop being the only one who doesn’t enjoy your shows.”

Just off the highway near the ferry in Tsawwassen, I unloaded my bags from the bus and turned to Cockburn. “I hope that wasn’t too painful for you,” I said, extending my hand.

“It was fine,” he replied, giving me a huge bear hug in return. I think that’s what I liked most about those four days on the road with Bruce Cockburn: being surprised by him. I had come expecting to be kicked off the bus. I left with the delicious feeling of having discovered a friend.

This article may not be reprinted without the author's written consent.

PRESS RELEASE

PRESS RELEASE

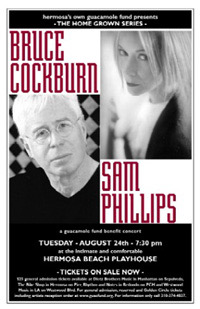

BRUCE COCKBURN AND SAM PHILLIPS TO APPEAR IN A BENEFIT CONCERT AT THE HERMOSA BEACH PLAYHOUSE

True North/Rounder recording artist Bruce Cockburn and Nonesuch recording artist Sam Phillips will be appearing at the Hermosa Beach Playhouse on Tuesday, August 24, 2004 at 7:30 PM in a special benefit concert for the Guacamole Fund.

The Guacamole Fund is a non-profit organization that produces events for educational, environmental, cultural, and service organizations that work in the public interest. This is the second in the Home Grown Series.

Bruce Cockburn, Canadian singer-songwriter and guitarist extraordinaire, has recently released his 27th studio album “You’ve Never Seen Everything.” Over the course of three decades Bruce’s ability to distill political events, spiritual revelations, and personal experience into rich, compelling songs have made him one of the world’s most celebrated artists. Along with his hall of fame induction, Cockburn has been honored with numerous awards since he first launched his solo career in 1970 including the Tenco Award for Lifetime Achievement in Italy and 20 gold and platinum awards in Canada. He will be playing solo acoustic.

Sam Phillips’s recently released latest album, “A Boot and a Shoe,” like her “Fan Dance," on Nonesuch is fiercely intimate in atmosphere and seriously stripped down in arrangement—not so much unplugged as beautifully unvarnished. Although Sam has long been admired for her coolly modern take on Beatles-esque songwriting and studio craft on Virgin Records, she decided to move away from elaborate pop production and 21st century technological upgrades with “Fan Dance.” Since then she has stuck to this road less traveled.

The Hermosa Beach Playhouse is a comfortable and intimate art deco theatre with seating for about 500 and is located at 710 Pier Avenue in Hermosa Beach at the corner of Pacific Coast Highway. There is plenty of free parking adjacent to the theatre.

Tickets are on sale now. General Admission tickets are $25.00 , there is no service charge.

General Admission, Reserved, and Golden Circle seating, including artists’ reception with Bruce and Sam, at www.guacfund.org or phone at 310 374 4837.

True North Press Release

Bruce Cockburn's penned gems get covered a lot...

Jimmy Buffet chooses two Cockburn songs for his current number one release.

TORONTO – July 21, 2004 - Bruce Cockburn gets covered, a lot. It’s been a great few months for Bruce Cockburn tunes with many of the titles from his extensive catalogue of songs being covered by various artists from around the globe. Bruce’s songs have now been recorded by over two hundred different artists including: Jimmy Buffett, The Barenaked Ladies, The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, Maria Muldaur, Dan Fogelberg, Anne Murray and The Rankins.

Jimmy Buffett has two renditions of Bruce Cockburn’s songs on his newly released CD License To Chill. License To Chill debuts at #1 in the US as of today’s date, with an incredible sale of 238,597 CD’s in the first week. Jimmy recorded the beautiful Anything Anytime Anywhere, which is the title cut of Bruce’s greatest hits CD released in 2001. Mr. Buffett also chose the song Someone I Used To Love, and turned it into a lovely duet with Nanci Griffith. Someone I Used to Love is originally on Bruce’s 1994 CD Dart To The Heart.

In February of 2004 English pop group Elbow released the song Live On My Mind from Bruce’s 1997 The Charity of Night CD, as the B-side to their last top twenty single in England.

kd lang’s new critically acclaimed CD Hymns To The 49th Parallel showcases her version of One Day I Walk which originally appeared on Bruce’s second CD High Winds White Sky in 1971.

Montreal Jazz Singer Ranee Lee takes the song My Beat and does her own interpretation of this song for the 2004 release Maple Groove. My Beat originally appeared on Bruce’s 2002 CD Anything Anytime Anywhere.

Irish blues singer Mary Coughlan just recently covered Blues Got The World which was originally recorded by Bruce for his 1973 release Night Vision.

Bruce Cockburn has recorded 27 albums for True North Records. His songs are timeless and his lyrics are as fresh as they were when he wrote songs like Lovers in A Dangerous Time, Wondering Where The Lions Are and If I Had A Rocket Launcher. Bruce’s latest release You’ve Never Seen Everything came out in 2003. Bruce is currently doing festival shows this summer across North America and will be touring Quebec in the fall. For complete tour dates please go to www.truenorthrecords.com.

Beggar with a withered knee ignites his guitar at the delta.

Beggar with a withered knee ignites his guitar at the delta.

Bruce Cockburn - solo

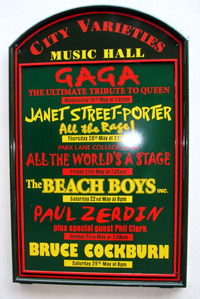

City Varieties Music Hall, Leeds, England

Saturday 29th May 2004

by Richard Hoare

Richard Hoare tripped off to see Bruce on a fine evening this past May. The following is an exclusive review of the show for Gavin's Woodpile.

This intimate 500-seater Victorian theatre was the location for Cockburn’s fourth gig out of five shows in the UK before he flew to Spain for his first ever gigs in that country.

Bruce opened with an uplifting Lord of the Starfields and settled into the evening with Lovers in a Dangerous Time, Open and Pacing the Cage. He started to flex his fingers with an extended introduction to Wait No More that culminated in a tour de force Down to the Delta that was a workout seemingly across the entire fretboard including a long new middle section. As his hands recovered Cockburn recounted a wonderful anecdote about a canoe trip he had been taken on in Northwest Canada down the Mackenzie River to the delta with the Beaufort Sea bordering the Arctic Ocean.

Bruce took us to the intermission with a dignified All The Ways I Want You before re-gearing for Tried and Tested and Trickle Down. The last song has been reworked for solo performance since I saw Cockburn play with Julie Wolf on his last tour.

The second set started with a quartet of songs played on the Guild 12 string – the great My Beat, the hypnotic All Our Dark Tomorrows, Let The Bad Air Out and the erotic Mango. There then followed the absinthe fuelled Night Train, The Last Night Of The World and the optimistic World of Wonders.

The audience brought Bruce back twice. Firstly for After The Rain, a classic from 1979, and Tie Me At The Crossroads. When he came back a second time, despite the usual barrage of requests he offered, "You won’t know this one – and it may yet be ephemeral – it’s called Mystery." Cockburn proceed to deliver topical lyrics with repeats in a sedate nursery rhyme fashion. Apparently bowing to requests he played out with the single Wondering Where The Lions Are.

At the end of the first set Bruce said he’d be back but countered that the Japanese cannot say that in their language, they say "I may be back" and by way of comparison Muslims say "I’ll be back, God willing."

Cockburn was in good humour but mainly communicated through his playing and lyrics rather than stage patter. There was no reference of his trip to Iraq and only a brief reference to Bush and Bin Laden before Tomorrows. Bruce was clothed in grey on a black stage with minimal lighting apart from during a few numbers in the second set when a back drop behind Cockburn lit up with an array of star lights.

What does it take for the heart to explode into stars?

The Language of Truth

Full Interview

Sojourners Magazine, April 2004

This interview was conducted on February 1, 2004

Musician Bruce Cockburn describes the real and the surreal in Baghdad.

With more than two dozen records and numerous international awards to his credit, Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn has earned a reputation as a globe-trotting troubadour who protests social injustice along with probing the spiritual realm. Cockburn traveled to Iraq in January as part of a religious delegation to assess the humanitarian situation there. Sojourners editorial assistant Jesse Holcomb spoke with Cockburn about his experiences.

Sojourners: I would like to hear generally about your trip to Iraq, but specifically, I'm really interested in your experiences as a musician and a songwriter there. How did it come about that you were a part of this delegation anyway?

Cockburn: I kind of invited myself along. Bishop Gumbleton, I think, was the one whose idea it was. I'd heard about it from my friend, Linda Panetta, with whom I've worked around, particularly on the School of the Americas stuff; she's been active in the School of the Americas Watch for a long time. And at one point we were sitting, having dinner in Philadelphia and she mentioned that they were planning on doing this trip and I said, “Well, you know, I could do that too.” I wasn't sure, but it looked like it was going to happen right when I had the time. And from that point, she mentioned it to Thomas Gumbleton, and he was fine with it, and Johanna Berrigan also. So I became a part of the trip. It was kind of down to the wire whether we'd cancel; they had planned an earlier trip that they did cancel because of changes going on in Iraq. So we were watching the events to see if it would become necessary to blow this one off, but as it turned out, we all felt that it was good to go, so off we went.

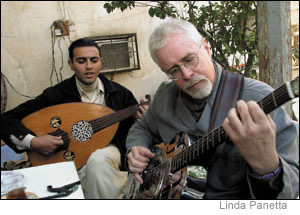

Sojourners: I read in a recent Canadian Press release - I think it was by Roberta Cohen - about your trip. It mentioned that you found some time to make music while you were there, and I was wondering if you'd describe that experience; how it came about.

Cockburn: There were a couple of different experiences like that. Mostly it involved me playing for people, which I hadn't really planned on, but I've been in enough of those kinds of situations to know that it does happen when you don't plan on it sometimes. So I was prepared for it. I played for the - well, I don't know what they're called - I was going to say "inmates,” but they're hardly that (laughter). A number of disabled women living in a shelter that was one of the places we visited. I played some songs for them [and] I played in the lobby in the lounge of the hotel that we were staying at. There were a bunch of NGO people, Canadians and Americans that knew who I was, and I had to practice anyway for this tour that we're now on, so they got me to do it in front of them.

But the most interesting point came when I got invited for lunch - we all did, actually - got invited for lunch by a visual artist that we had been introduced to and who was fond of cooking a particular kind of fish that they have there, according to a Sumerian recipe. It was just amazing to be in a place where the people are using recipes that go back 2500 years or more. He said he was going to invite a young ud player. Ud is the Arabic lute that's very characteristic of Middle Eastern music and the precursor to the European lute and modern guitar. And I got to play with this young guy who was quite good and had a lovely singing voice, and he played and sang songs - I didn't even know what the songs were about because, obviously, he was singing in Arabic. But he played, then we had lunch, and then I played and he started jamming with me so we ended up in this kind of improvised jam that really worked. It was exciting to play with somebody whose background was so totally different but whose ears were really tuned. And we were both kind of careful to not get in each other's way and to try to complement what each other was doing, and it worked, really well.

Sojourners: Not everything works really well in Iraq these days…

You don't speak any Arabic, so how were you, as a group, able to communicate and interact? What were some of the challenges and some of the possible breakthroughs, moments of clarity, or experiences with the people you met?

Cockburn: Well, we were aided and abetted by people from the American Friends Service Committee. They provided us the drivers, at least arranged for us to have drivers who were local guys, so we always had somebody with us that spoke Arabic, although the drivers were not very fluent in English, they couldn't act as translators, but they could troubleshoot if that came up. But as it turned out, it didn't really. Most of the people we met spoke some English. And where that wasn't the case there was somebody around who could translate. We went to a squatter camp where somewhere in the neighborhood of 500 families were living in this bombed-out building, which is a scenario that's repeated around Baghdad, but in this particular one they didn't speak English really; they might know a couple of words. But we had people with us who were sort of our credibility as far as homeless folks are concerned and who also spoke English, so they were able to translate.

Sojourners: So are squatter camps and bombed-out buildings more, or less commonplace than the media are telling us? Describe some of the images and urban landscapes you saw that left an impression or an impact on you.

Cockburn: The thing that's interesting, that struck me about Baghdad right away is that it doesn't immediately look like a war zone. It doesn't look like a city that's been under attack as much as it has. There are plenty of bombed-out buildings to be seen, but they're interspersed because they were selected by the US forces so-called "coalition.” They were the ones they actually tried to bomb. So you'll be driving through a neighborhood that actually looks like a pretty functional neighborhood, although terribly rundown after all the years of sanctions, and then you'll come upon a large building that's been blown to smithereens and then you turn out past that and you're back to into something like a normal city again. So it's not like a rubble-strewn landscape the way you'd picture the way Hanoi must have been, for instance, when they were bombing Hanoi; the way European cities looked after the Second World War. It doesn't give you that same impression. So the bombed-out buildings, in a way, are a lot more striking because of that contrast.

And there's an air of surrealism in a way, about the place, because you have what half the time looks like it should be a functional city, but it doesn't have reliable electrical power; no traffic lights work in the whole city - 5 million people in a city with no traffic lights and lots of cars, and the cars are all older models, run-down, bald tires - because for years they had no means of repairing anything. So streets are not in good shape, the buildings are not in good shape, the cars are not in good shape. That was before the war, and then the war has added to this scenes of bombed-out buildings.

But there were government buildings - interestingly enough, the two ministries that they didn't bomb were the oil ministry, which was fairly predictable and the interior ministry, which I found very interesting. That they chose to leave that standing. And immediately my suspicious mind went to work and I said, "Well yeah, they wanted all the records from there.” And a girl who happened to be sitting near me when I said that said, "Yeah, that's what all the Iraqis think too.” That's where all the secret police records were, and all the files. And they didn't bomb that. I don't know what the motive was, and you could ascribe anything to it, but it was noticeable because those were the only two government ministries that were not bombed. The oil ministry made perfect sense in the logic of - I mean as much as anything made sense about that whole exercise. But anyway, that's kind of an aside. But it was just strange - unlike any place I'd been in. I've been in countries and cities that were at war, but the cities were not themselves under attack. The vibe was very different in this case.

Sojourners: Are there any other experiences from this trip that captured your artistic attention?

Cockburn: I tried to write down everything that I could think of, and everything I saw, so, I guess the only thing that made a really big impression on me that I - well, there's so many impressions, really. They're not the kind of impressions that are readily reducible to songs so far, but we'll see. Sometimes these things take time. "Postcards from Cambodia” took a long time to write for the same reason - it just was hard to figure out how to approach that.

But the Sunday morning that big bomb went off, which was the first morning after that period of relative calm, we were told that we were there during the quietest week that they could remember. And obviously it heated up again pretty soon after we left, because that bomb was just the beginning of a whole string of them that have been going on daily, since. But that one big bomb at the entrance to the CPA headquarters - I happened to be standing there looking out my window; the hotel room I had had French doors, opening onto a little balcony which overlooked a regular street. And it was a Sunday morning, which is not a holiday there. Their holy day is Friday, so Sunday's a regular workday. People were going about their business, 8 o'clock in the morning; people were walking up and down, whatever. And there was just this big boom in the distance. But what struck me was nobody registered it at all. Nobody moved, nobody turned their head to see; there was no sense that they'd even heard the sound. And obviously they did because there was no mistaking it. I found that really telling, in a way, and I assume it's because they're so used to things like that happening that they're immune unless it's happening right next to them. So that struck me with great force. That whole moment is kind of etched [in my mind], because there was the sound of the bomb, and it was a clear sky, a nice sunny morning, and it was - there was nothing to see, I was a couple of miles away from where it went off, and - although I didn't notice it rattle or anything, my friends were having breakfast downstairs and they said it rattled the silverware on the table. I wasn't aware of that, but there was this moment of stillness after the initial sound and then you hear sirens start up pretty soon after that. People walking in the street, like I said, went about their business and registered absolutely nothing. I'd like to be able to get that into a song somehow.

Sojourners: It would get the wheels turning, I'm sure.

Cockburn: There was [another] moment - coming down into Baghdad International Airport is amazing. The airport itself is a modern, glass and steel structure; I mean, it probably was bombed, but they repaired it right away. And there are no commercial flights going in and out of there; there were a couple of cargo planes and lots of military aircraft around, but we flew in from Amman, Jordan on a flight operated by an NGO called Air Serve that is devoted to doing mercy flights and other kinds of stuff - I assume they're on a contract with the UN to fly in and out of Baghdad. But there were about ten of us on this little twin engine (unclear) craft plane, and it flies directly over the city of Baghdad - directly over Baghdad Airport. And then - without lowering its altitude at all, at the last minute, it just starts to corkscrew right in over the airport so you're practically on your side for the last few minutes of the flight in order to avoid ground fire, of course, but it was quite spectacular. And then we get off the plane, walk into this terminal, this big glass and steel terminal that says Baghdad International Airport on the front - and we're the only people in there. There're four Iraqis in uniform manning passport check booths, and some Gurkas that were part of a private security company doing security for the airport that were standing around. But other than that, we were the only traffic in the airport. And that too - as an introduction to the place, there's a strange eeriness about that feeling in this big empty building.

Sojourners: So you made your observations and you registered facts while you were there, but I'm wondering how you as an artist tell the truth, as opposed to simply reporting the facts.

Cockburn: I don't know how it will work out, I mean, I have no idea whether I'll get a song out of this or not. It's hard to really address it as a songwriter per se, without having a specific song to talk about. But in terms of telling the truth of what was there, I can do two things. I can give my own impressions, which I'm doing right now, and I can quote the people who I talked to. Because what I can bring back that people don't already get from watching CNN [are] the feelings of those people that we met, and the ideas that they have about their situation, and so on. That's the reason I wanted to go in the first place; to see what it felt like for the people who live there.

Sojourners: Were the people open to you?

Cockburn: Very much so, and even when there wasn't language [in common]. The Iraqis generally have a longer stare threshold than we do. And they look you right in the eye and they kind of "gimlet-eye” when you walk into a room. Like in the couple of the hospital visits that we did, for instance, there'd be people standing around and they'd kind of be looking at you. And as soon as you said hello, they'd break out into these great big smiles and say, "you're welcome!” It was this beautiful sense of hospitality right away, soon as you indicated any friendliness at all. And I think they become used to seeing foreigners as intruders, obviously, and occupiers, and people who go around acting like occupiers. When you see the news media people - the mainstream media people at least - and the military, and the CIA or whoever they are in plainclothes with guns, they're going around in armed convoys of matching white suburbans wearing flat vests and, you know, it's really conspicuous and an unmistakable statement is being made whenever they do that. "We're running this place right now.” The Iraqis are a very proud people and they're very sensitive about stuff like that, so for us to actually be there, kind of on their level, I think they found that quite appealing. And they were very open. They're people who like to talk anyway, just like we all do. I mean, you get to talk to somebody from outside who hasn't heard your story before, they're happy to tell it.

So we met a wide range of people, everybody from the (unclear) to the inhabitants of this squatter camp, and everything in between. Women's groups, human rights groups, a fair number of religious people because of Bishop Gumbleton's particular priorities. And it was really interesting. I had no idea, for instance, that there was a Christian population in Baghdad or in Iraq. There are and they go back to the earliest days of Christianity. They're referred to as Chaldean Christians, and they speak Aramaic. You know, I though that was dead! These are things I'd never seen anywhere in the media, and as is not unusual, the mainstream media are oversimplifying the situation in Iraq, in a not very constructive way. I think a lot of Iraqis felt that the media are creating some of the divisiveness that we're hearing about between the Shiites and the other folks, for instance. That before the war, and up till the war - till Saddam had fallen, there was none of that. You could go anywhere in the country and everybody was equal and nobody dumped on anybody else because of their faith. And they still feel like that is there, except the media are creating this atmosphere of tension and insecurity particularly around the Shiite majority's desire to establish an Islamic state.

Sojourners: Speaking of religion in Iraq, did you get a sense of the role faith plays among the people? Either in a civic or personal sense?

Cockburn: I'm not sure if I met a big enough cross-section of people to really have a good handle on that, but certainly it played a varying role. It actually struck me as being very similar to how it would be in North America if you were to make a trip like that. Obviously, as I said, we met a lot of people, a lot of religious leaders and other religiously affiliated people because that was part of what Bishop Gumbleton wanted to do. And it was very enlightening to do that, but among the other people that we met, I'd say it was about 50/50 between people who appeared to have put their faith in a central position, compared to people who were more secular in their inclinations, not particularly concerned [with] the faith. The women's groups, for instance, were not keen on the fundamentalist view of women, particularly the traditionalist view. More than once we heard somebody say - a woman would say this is - she would talk about the fundamentalist vision of an Islamic state and refer to it as "their” idea of Islam. Making a clear distinction between their interpretation of scripture or tradition and what's really there. I've been reading the Koran but I've only gotten a little way through, so I can't address what it says about that.

But the big thing on everybody's mind and the thing that you really notice is fear. Not so much of the Americans, although that's an issue, but of crime. Because there's no law and order. The existing law enforcing systems were shut down, and, I mean, the country doesn't have a constitution, doesn't have a real functioning government. It has a police force now, but that police force spends most of it's time defending itself against people who see them as collaborators, and bombing them and shooting them and so on. So people are really nervous about sending their kids to school in case they get kidnapped or sold off into who-knows-what, or in case there's just violence there. The US military is staging house raids almost daily, looking for whatever, (unclear) and people get stopped sometimes in the course of those things or disappear into the prisoner system. Iraqis don't have a very good handle on that because they're not allowed contact with people that are arrested; none of the legal safeguards that we think should be in place are in place on any level. So if your husband or mother or cousin or whoever gets arrested, it's going to be months before you find our where they are or what happened to them.

Sojourners: So this atmosphere of fear - this bleakness, lack of infrastructure…I mean, these are things that you've seen before.

Cockburn: Not quite in the same mix, though. It's a really different vibe from Nicaragua, for instance, where everyone was at war. Everybody felt the presence of warfare and you were kind of on one side or the other. Maybe if you went to Nicaragua now it would be more like this, like what I saw. But my experience of Nicaragua under the sandinistas was [that] there was very little crime - not significant amounts of street crime, robbery, or any of that kind of stuff - it just wasn't happening. And here it's actually the main problem, aside from the bombings. But people are just really worried. Those who can afford to have armed guards have armed guards around. The street that our friends are living on, landlords on that block had hired these guys to keep an eye on their property. So there's always several men with AK-47s standing around in the street. In their street. But their job is to prevent petty theft as much as anything else, but they're the closest thing to a regular police force you're gonna find, except in very limited circumstances where the Iraqi police are kind of working with the Americans. I'm tempted to say its kind of more of a middle-class fear. Because Baghdad was a well-to-do city. I mean, it was a thriving first-world city before the sanctions started. It doesn't have the vibe of a third-world postcolonial place.

Sojourners: The final lyric on your recent record is the word "hope.” And I've noticed that you seem to occupy what in my perception is an ambivalent space in your recent songwriting, between what might be a temporal disillusionment and an eternal longing, something like what we hear in "All our Dark Tomorrows.” But there's also a juxtaposition of redeemed carnality against the backdrop of something foreboding. In light of the situation there in Iraq and elsewhere in the world, how can there be hope and meaning in such a grim context?

Cockburn: It's very hard to generalize about that, but for me, I feel that everything is unfolding as it must. Not from detail to detail, moment to moment, necessarily, but in the broader strokes. I think that the things I encounter are things that God has at least permitted, if not deliberately put in my way. And therefore hope or not-hope is kind of a non-issue. It's just about reality. We all make up this universe together, or creation - if you want to call it that. And everything that happens touches everything else that happens, and that applies to us and to our own personal movements in both our interior and exterior as much as it applies to what we might think of as accidents of nature. Creation is an unfolding thing and we're part of that unfolding in our excesses; our violence, our coldness toward each other, our lack of humility, our lack of compassion are as much a part of that unfolding as their opposites. So personally I don't feel like anything's going to happen to me that isn't supposed to happen. Therefore, what's to be hopeless about? And it doesn't require courage to think that way; it's just the way it is. And that doesn't take free will out of the picture either. I feel like I'm confronted by choices all the time. I have the capacity and the freedom to make choices.

Sojourners: Freedom's not necessarily light or easy, though. In "Tried and Tested” you speak of the "burden of choice.”

Cockburn: In effect, yeah. And choices are made, inescapable; even if I pretend not to make a choice I've still made some kind of choice. So over the years I've sort of come to appreciate the value of actually deliberately making the choices instead of pretending that I wasn't doing that. I use the word "hope” in that song ("Messenger Wind”) and other places because it's a word for something that we all feel in our hearts, but if you actually analyze it, it's just - what is.

Sojourners: Are there any political-moral imperatives that have gripped you after your visit to a country at war?

Cockburn: The thing that comes immediately to mind is that George Bush has to go. One way or another he's got to get out of there, and his gang with him. [But] it may not happen in the next election. I worry about this, because Americans like things to happen right away or they give up on them. If the attempts to unseat Bush do not succeed this time around, what I really hope is that people won't get discouraged by that, [but will] feel even more driven or inspired to work for a stronger opposition to him next time around. Or to what he represents, because it won't be him. The neo-conservative agenda is an inhumane, thoughtless, disaster-laden agenda, and it's got to go.

Sojourners: In light of this American short-term memory, this capacity to be easily distracted - what do you think it would take to reach and inspire a younger generation to respond to these global power plays?

Cockburn: That's an interesting one, because I think a lot of young people are responding to what they see as the phoniness of the world - what they see as encroachments on their own future, by business, for instance. They're the ones driving the World Trade Protests and all that. The young people. And yet they're not showing up to vote, which suggests that there's a cynicism about the voting process or a lack of faith in it, certainly, and I think that lack of faith is well founded. But at the same time, it would be really helpful if that energy and that willingness to move forward could be channeled into the electoral process. I think that we'd all be better off for it. So that's a challenge, I don't know how you do that. There are things like Rock the Vote and all that, and that helps, but I think that's where there needs to be a real push. To get young people to feel that they can actually make a difference by voting.

Sojourners: Do you think that music in any way plays a role in giving a language to these feelings? Can it help?

Cockburn: Certainly it can. It has to be the right music though, because kids aren't listening to everything. It requires credibility on the part of the people that are making the statements to them. Kids will see through phoniness right away. If somebody stands up and says "get involved in this or that” and they don't look like they know what they're talking about they're not going have an influence of any valuable kind. In some ways youth has to find its own way, I guess. That's always how it is. I remember in the Sixties when the concept of youth as a political force was a new thing, there were older people around who were inspirational as all get out. There were people who would say, "look, it's on you - it's your future.” And we would listen to people like that if they came with the right credentials. I don't know who the people are that would have the right credentials at this moment, but they've got to be there, and somehow we need to get them speaking to the youth.

Sojourners: How do you see your role as a songwriter and as a musician in mobilizing, truth-telling, or speaking truth to power?

Cockburn: Well speaking the truth is it, exactly. That's my role. My job is to take what I understand to be true and try to put it into a communicable form. That's what I do as an artist and on the periphery of that are other kinds of involvement, like the benefit we just did to help out people who are fighting a toxic waste incinerator in New Brunswick. [It's] a little village that you can barely find on the map, and it's exactly the kind of situation where business interests go in and say, "We can manipulate the situation easily.” People need jobs, therefore…etc. etc. And some of the people feel that way and other people don't, so there's been a strong resistance to this without any help from the provincial government, which is totally on the side of business. So it's at least a morale boost to have somebody from outside show an interest, somebody with a bit of a public profile. And hopefully it will have meant more than just a morale boost. But we were able to raise some funds for their efforts and so on. So those kinds of things happen around the exercise of the art as well. And that's going to continue in various ways.

Sojourners: But I wonder if there aren't ever certain messages or feelings that can't be truly expressed. With your trip to Iraq, for example, was there anything that got lost in translation?

Cockburn: Well [my] job is to try not to have that happen. When I write a song like "Postcards from Cambodia” or "Mines of Mozambique,” those kinds of landscapy songs, I try and get the atmosphere of a place. I try to be as precise as I can with it and I guess it works for some people.

My thanks to Jesse Holcomb at Sojourners Magazine for permission to reprint this interview. DK

April 30, 2004

Chicago Sun-Times

Troubadour lends his voice, and ear, to Baghdad

by Cathleen Falsani

I'm sure he doesn't remember it. Actually, I pray he doesn't, but I don't know for certain because I didn't have the guts to bring it up when we spoke on the phone the other day.

The scene of the crime: Backstage at a theater in Ann Arbor, Mich. About a dozen years ago.

Bruce Cockburn, the Canadian singer-songwriter probably best known (unfortunately) for the song "Rocket Launcher," had just finished playing a gig and graciously agreed to meet with some local press, including several reporters from college newspapers.

There we were, one of my roommates and I: 20-year-old aspiring journalists, booklearned, desperately earnest and -- with the benefit of hindsight, I've since realized -- hopelessly myopic about the reality beyond our own itty bitty universe.

We were very excited. Bruce was our favorite, all folk-rock tough and kind of Jesusy.

Cockburn had played a couple of hours worth of gorgeous, rousing songs about faith and love, justice and war, suffering and South American death squads, pestilence in Africa and corrupt governments, physical torture and spiritual bullying, unthinkable oppression and divine grace.

His music is sacramental, we told each other, flushed with inspiration and righteous indignation. I really thought I got what he was saying.

Wrong.

"Bruce, man, our school, it's so oppressive," I remember telling the down-to-earth singer as he twisted the top off a beer and listened to us, indulgently.

"Oppressive?" he gently asked.

"Yeah. Like, spiritually oppressive and judgmental. You wouldn't believe it," I said, referring, with great pathos and gesticulations, to the conservative religious college we attended.

"That's tough," Cockburn said, still kindly.

A real redemption song

He probably wanted to reach across the table and smack me out of my privileged American white-girl stupor. But he didn't. He answered our questions, shook our hands and sent us on our way.

Each time I remember it now, I die a little.

But one of the joys of life is the opportunity for redemption. So when I learned Cockburn, who has been a social justice activist as long as he's been a professional musician, had recently spent a week in Iraq, I picked up the phone to see if I could have a do-over. My cosmic mulligan would not be squandered.

This time, I'd get it.

As he has on several occasions before in Mozambique, Nicaragua and elsewhere, a few months ago Cockburn, 58, slung his shiny Dobro guitar over his shoulder, and with little else besides an inquiring mind, headed into the Iraqi war zone to see what was happening.

Along with a photographer, a peace activist and Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, the Roman Catholic auxiliary bishop of Detroit, Cockburn spent seven days in Baghdad looking and listening. The musician -- a modern-day troubadour, really -- met religious leaders, human rights activists, scientists, artists and regular folks.

"There were a lot of different people and . . . everyone that I talked to seemed extremely well educated, actually, and very aware of the world at large," Cockburn was telling me the other day. "[Baghdad is] pretty hurting after 13 years of sanctions and a year of battering from this war."

"It's a big city, first of all. It's 5 million people and it's got a lot of traffic. The traffic is chaotic and bizarre because there are no functioning traffic lights," he said. "I went to one squatter camp in a bombed-out building where there were 500 families living in these ruins."

Cockburn's guitar went along with him. He jammed with a young Iraqi oud player, serenaded a house full of disabled women, and practiced tunes in the lobby of his hotel where most of the guests were Shiite Muslim pilgrims from Iran in town to visit holy sites around Baghdad. They had been banned from the sites under Saddam Hussein's regime.

At one point, on his way to lunch with the owner of an art gallery in downtown Baghdad, Cockburn's car got stuck in a traffic jam and he had to get out and walk. Which is how he found himself in the middle of a 100,000-strong demonstration of Shiite Muslim men.

So, did they wonder who the salt-and-ginger-haired guy with the guitar was?

"They kind of looked at us like that, but as soon as we smiled and said hello to people . . . they'd break into these wide grins and say, 'You're welcome,' which, for most people, was the extent of their English," he said.

Quest for connection

Why does he make these trips? Why bombed out theaters in Iraq, refugee camps in Guatemala, mine fields in war-torn Mozambique? He's a celebrity, after all. He could be kicking back with an umbrella drink at a spa in the South Pacific.

"In general, I kind of feel it's my job to know what's going on, and also to help in any way that might be offered," Cockburn said. "It's my job to tell the closest thing I can to truth in my songs, about what it is to be human in this world. Situations like what Iraq is facing are all too common in the world. It's important for me to have a sense of how it feels for people living with that."

Cockburn's journeys and how he recounts them in music also are a matter of faith for him. Early in his career -- the first of his 27 albums was released in 1970 -- he wore his Christianity on his sleeve. Today, his faith, though clearly deep, appears slightly less sectarian. Evolved, he might say.

"My understanding of my relationship with God includes an invitation to be involved in what goes on in the world and to try to offer positive input wherever possible. And that goes with being human, beyond being an artist," Cockburn said.

"I feel we're in a race," he said. "We're in a race between our ability to understand our relationship to the divine in a kind of nonpartisan way, let's say, which includes a sense of interconnectedness of all things, including us.

"With the minute choices that we make, and the steps that we take in life, we're kind of in a race between that understanding and an innate urge to self destruct."

Cockburn, who became a grandfather for the first time earlier this month, is heading out again soon on a European summer tour in support of his latest album, "You've Never Seen Everything." He hopes to return to Iraq.

In the meantime, he'll likely make new music about his week in Baghdad, he said, much like the dozens of songs he's written about reality as he's experienced it elsewhere in the war-torn and developing world.

So people who would otherwise not understand might get it.

Copyright The Chicago Sun-Times, Inc.

From Australia

March 9, 2004

The Age

Songwriter's taking care of business

Bruce Cockburn doesn't just write songs about trouble - he's been there, reports Warwick McFadyen.

"I just see it as part of my job." Singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn is explaining why he visited war-ravaged Iraq in January.

"I wanted to get a sense of what it feels like to be living in Baghdad," he says.

"But, in a deeper way, I just see it as part of my job to understand as much as I can of human behaviour and the human experience."

The explanation goes to the core of Cockburn as an artist.

Twenty years ago, the Canadian singer found himself in a firestorm over the song If I Had a Rocket Launcher, which he wrote in response to helicopter attacks on a refugee camp for Guatemalans in southern Mexico that he had visited.