December 27, 2015

From Ben Rei

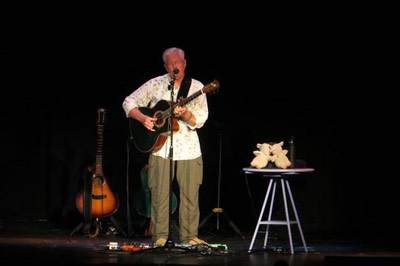

My thanks to Ben for the setlist and photos from Bruce's two Christmas concerts at the San Francisco Lighthouse Church on December 11 and 12, 2015. The setlist was the same both nights. -DK

1st Set

1. World Of Wonders (Bruce solo)

2. Last Night Of The World (Bruce solo)

3. All The Diamonds (Bruce solo)

4. God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen (with A Capella vocal ensemble coda)

5. I Saw Three Ships

6. Lord Of The Starfields

7. We Three Kings (instrumental, with TS Elliott poem read by Jeff Garner)

8. Early On One Christmas Morn

9. Go Tell It On The Mountain (lead vocal by Thadeus Lee)

2nd Set

10. Lovers In A Dangerous Time (Bruce solo)

11. Emanuel (solo vocal by one of the female singers)

12. Sunrise On The Mississippi (Bruce solo)

13. Lament For The Last Days

14. Mary Had A Baby

15. Shepherds (original 1976 version)

16. Cry Of A Tiny Babe

17. Away In A Manger (solo A Capella vocal by one of the female singers)

18. Les Anges Dans Nos Campagnes

19. Joy Will Find A Way (encore)

December 7, 2015

Bruce Cockburn – Three 2015 UK Shows

Reviewed by Richard Hoare

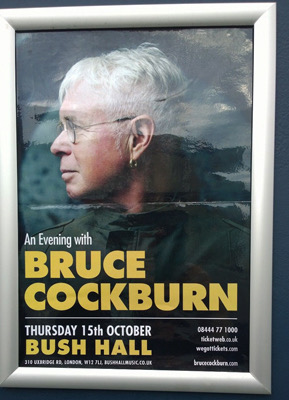

The Stables, Milton Keynes Tuesday 13th October

Bush Hall, London Thursday 15th October

The Gate Arts Centre, Cardiff Saturday 17th October

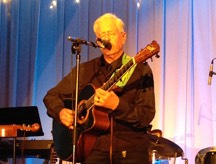

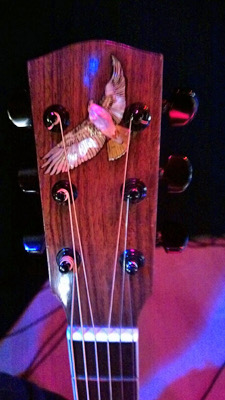

I attended three of the eight UK shows this October. Bruce Cockburn brought with him three of his trusty instruments made by Linda Manzer all with interesting inlays in the headstocks. The six string has a red-tailed hawk, the twelve string a round face, an image from the 1902 film, A Trip to the Moon, and an abalone shell in the ten string charango. The stage set-up included two small tables, one for the tuner and effects controls and on the other sat two apparently woolly toy sheep.

Two years ago, in November 2013, Cockburn played a single UK show at Bush Hall in London, and the last CD of new work, Small Source Of Comfort, was released in 2011.

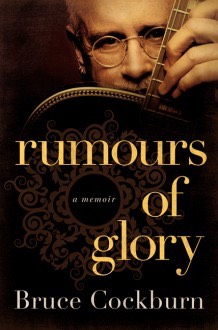

Bruce introduced Rumours Of Glory by explaining that he had been hung up writing his memoir for 3 years, not writing songs, but here was the title song of the book. Cockburn went on to say that he was trying to throw off the mantle of author to get back to writing songs. He also added that he wasn’t promoting a new album, just playing the same old songs! In fact this notion had a liberating effect on how he selected the set lists from his wider catalogue. While there were core songs across the three gigs Bruce introduced some great variants here and there.

At Milton Keynes Cockburn settled into the set with Last Night Of The World and Night Train before playing a beautiful After The Rain. Rumours Of Glory was introduced as written about New York on a grey day. Open and Lovers In A Dangerous Time followed, topped off by an exquisite Bone In My Ear on the charango.

Planet of the Clowns, which I had not heard in the set list for years, was played against the background of the sound of the sea produced by the woolly Sleep Sheep. This background effect continued for a rendition of the instrumental, The End Of All Rivers, which as Bruce commented, is the ocean. This latter piece provided Bruce with a canvas to stretch out over with some intense and fiery guitar work. The maritime trilogy was completed with a beautiful performance of All The Diamonds, which also concluded the first set.

Cockburn opened the second set with the melodious instrumental, Sunrise On The Mississippi, another track not played live for a while, followed by Whole Night Sky. There then followed a couple of beautiful songs from Dancing In The Dragons Jaws. The rarely-played-live Hills Of Morning and the ubiquitous Wondering Where The Lions Are. If A Tree Falls reminded us again of climate change and he then swapped his six string for the twelve string for the last three songs of the set – God Bless The Children, Jesus Train (out of four new songs the only one currently fit for the public) and a rousing Put It In Your Heart.

The crowd called Bruce back for some encores and were unexpectedly provided with an instrumental verse of Rule Britannia followed by Pacing The Cage and Lord Of The Starfields.

The Stables had been two thirds full, however Bush Hall was, like in 2013, sold out with a number of the audience standing. The room was humming hotter and you could see Bruce was responding.

The set list was the same as Milton Keynes with the addition of If I Had A Rocket Launcher in the second set. After Night Train Bruce referred to everything being sun at the time of the first three albums, i.e. Sunwheel Dance. However, since then there has been a lot of night – in a good way! Unusually the heat put the charango out of tune. After Hills Of Morning Bruce put us off the scent by playing a blues instrumental introduction to Wondering Where The Lions Are, but that didn’t stop the whole audience singing the chorus. The encores that night were Lord Of The Starfields and Mystery.

The Cardiff show didn’t sell out, punters possibly being put off by the traffic generated from a Rugby World Cup Quarter Final down the road at The Millennium Stadium. To my surprise however, four different numbers had been substituted into the first set. The show kicked off with the sprightly instrumental Bohemian Three Step and Iris of the World, followed by a wonderful Strange Waters with great guitar solo. After the title song of his memoir we were treated to Mango with that beautiful kora style guitar. To encourage audience participation on Wondering Where The Lions Are Bruce offered “We are small but potent!”

The breadth of Bruce’s catalogue that he can currently play was further demonstrated by a couple of sound checks I caught where he aired the new City By The River, All The Ways I Want You, Anything Can Happen, Rouler Sa Bosse and a traditional carol from his Christmas album which I won’t name here and spoil for the upcoming San Francisco shows.

Three gigs over five days, a wonderful immersion into the soul and song of Bruce Cockburn.

Ricky Ross of Deacon Blue interviewed Bruce for Radio Scotland to coincide with the UK tour and offered some astute observations making for an interesting conversation. In the late 1980s I was back stage at a Greenbelt Festival in Northampton, England, when Ricky appeared wanting to have his photograph taken with Cockburn. They were both wearing black leather jackets. Ross enthused about Bruce and his work suggesting he was going to cover a Cockburn song one day. I have yet to find one!

And finally, although Bruce did not articulate it, he was in a way promoting the box set of CDs tied into his memoir. On the face of it the track list may look like you have most of the music already but the tracks include some remastered songs from albums not yet released in that format as well a few otherwise unreleased gems.

Photos by Richard Hoare

November 18, 2015

D. Keebler

Christmas With Cockburn Live, Featuring Bruce Cockburn with the singers and players of San Francisco Lighthouse Church

You can find details and ticket information for the two Christmas shows that Bruce will be performing in San Francisco at this link.

Christmas With Cockburn Live, Featuring Bruce Cockburn with the singers and players of San Francisco Lighthouse Church

Bruce will be performing at the San Francisco Lighthouse Church on December 11 and 12, 2015. In an email, Bruce told me “The shows will be benefits for social programs the church runs.”

Tickets are expected to be limited to about 400. You can learn more about the event at the church's webiste.

November 6, 2015

Albuquerque Journal

Bruce Cockburn on tour in support of ‘Small Source of Comfort,’ stops at the Lensic Performing Arts Center

by Adrian Gomez

SANTA FE, N.M. — For more than 40 years, Bruce Cockburn has done everything his way. Whether it is in his public or private life, the singer-songwriter has used his music to give a glimpse of what it’s like to be him.

Oh, not to mention he penned his memoir “Rumours of Glory” in 2014, which gave a deeper look into his decades-long career.

“I’ve always searched and found out things for myself,” he says during a recent phone interview. “I wanted to see everything firsthand. This is the way I chose to live.”

Cockburn has created a career most would envy. He’s picked up a dozen or so Juno Awards (Canada’s equivalent to the Grammy Award). He’s also recorded 31 albums, with his latest being “Small Source of Comfort.” The album is a blend of folk, blues, jazz and rock. It was inspired by his trips around the world, including San Francisco, Brooklyn, N.Y., and Kandahar, Afghanistan.

“The songs are representative of what I feel,” he says. “I’m impacted by everything that I get out and see. That’s the best part about touring – I get to see the world.”

There are five instrumentals on the album. “Each One Lost” and “Comets of Kandahar,” stem from a trip Cockburn made to war-torn Afghanistan in 2009. The elegiac “Each One Lost” was written after Cockburn witnessed a ceremony honoring two young Canadian Forces soldiers who had been killed that day and whose coffins were being flown back to Canada. He says it was “one of the saddest and most moving scenes I’ve been privileged to witness.”

Cockburn will continue to write and release more music.

“As you go through life, it’s like taking a hike alongside a river,” he says. “Your eye catches little things that flash in the water, various stones and flotsam. I’m a bit of a pack rat when it comes to saving these reflections. And, occasionally, a few of them make their way into songs.”

November 6, 2015

County Weekly News

Film Serves as Fundraiser

PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY, ONTARIO - Al Purdy was an icon.

Looming tall, almost always with mad, fly-away hair, a cigar in his mouth, a drink in his hand, pounding away at his typewriter or lounging by the lake. What a character. And what a writer.

Filmmaker Brian Johnson has crafted a moving and complex portrait of the artist in his documentary film “Al Purdy Was Here” to be screened at the Regent Theatre in Picton in advance of the film’s full release next year. On Dec. 12, at 1:30 p.m., Purdy fans and aficionados, theatre-lovers, film-lovers, Canadiana and literature lovers, poets, readers, neighbours and friends are invited to come together to raise funds and spend a most-excellent afternoon bringing this Canadian icon to life.

The film was a hit at Toronto International Film Festival in the fall and features an outstanding array of Canadian icons, both literary and musical: Leonard Cohen, Bruce Cockburn, Gord Downie, Gordon Pinsent, Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Sarah Harmer, Tanya Tagaq and Joseph Boyden to name a few.

The screening is a fundraiser for two local organizations; The Al Purdy A-Frame Association – raising funds to support the upkeep of the famous A-Frame cottage and the writers-in-residence who come to work there and Festival Players – raising funds to support its world premiere production of A Splinter in the Heart, Purdy’s only novel, adapted for the stage by playwright Dave Carley.

In the mid 1950’s, when Al and his wife Eurithe bought the plot of land on the south shore of Roblin Lake in Prince Edward County, Purdy was just beginning to find his voice as a poet. The space played host to a who’s who of Canadian Literature, Purdy holding court and hosting the likes of Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, George Bowering, Margaret Laurence, Earle Birney and more. The A-Frame, which had fallen into disrepair over the years, was purchased and refurbished by a Canada-wide initiative to maintain this legendary literary space.

In 2014, after a great deal of structural work had been done on the property by numerous volunteer groups, the cottage was ready to receive its first batch of poets-in-residence. These residencies allow writers time and a space to write, to focus on their work. Writers are provided travel funds, a writing stipend, and a cozy and historied retreat.

Festival Players, celebrating its tenth anniversary season in 2016, has been bringing high-caliber professional theatre to the region since its inception. Artists from across the country have joined the company to perform, design, compose, and create for the appreciative resident and visiting audiences. In the tenth season, the company is focused on stories by, for, and about Prince Edward County. One of the pieces in the season will be a stage adaptation of Purdy’s only novel, A Splinter in the Heart. Dave Carley, a prolific and accomplished playwright whose deep respect for his subject is clear in his work, has tackled the translation from page to stage with aplomb.

Splinter is set in 1918 in Trenton. WWI is coming to an end but the British Chemical Plant in town is still in full swing, producing half of the TNT for the allied war effort. Patrick, the young protagonist, is struggling with looming adulthood and with his place in the world. On Thanksgiving Day the British Chemical goes up in flames and flattens the town in a nearly Halifax-sized explosion. Life for the town, and for Patrick, is never the same. Workshopped in 2015, Splinter will be Festival Players’ mainstage production in 2016, the jewel in the crown as it celebrates a great story, a great story-teller and a little known piece of this country’s history.

On Dec. 12, the afternoon begins at 1:30 when guests are invited to grab a drink or a snack, browse the Purdyana, rub elbows with some lovely folks, get a copy of the A-Frame Anthology or tickets to the premiere of Splinter in 2016, browse some interesting and rarely seen bits of Purdyana. Filmmaker Brian Johnson will host a Q & A following the screening.

Interview date: October 26, 2015

Published winter 2016

Canadian Dimension

Bruce Cockburn: The Morale Imperatives of a Modern Troubadour

by Mark Dunn

Read the interview HERE.

October 9, 2015

The Scotsman

Bruce Cockburn - St. Andrews Square, Glasgow

Review by Fiona Shepherd

If anything, the solo, acoustic format of this show threw his dexterous guitar playing into even more impressive relief than usual, his hypnotic mix of picking and strumming providing the backbone for his songs, with his own vocal rhythms woven into the fabric, creating mood music as much as protest song.

The two strands came together via the cascading chords of his environmental warning If A Tree Falls. Like the solidly scathing Call It Democracy, it was written almost 30 years ago but could have been composed yesterday.

Cockburn raised consciousness in other ways too, transporting the listener with ringing New Age chimes over strident strumming, using an ambient field recording of waves to enhance the mesmeric reverie of his playing and utilising the heavenly harp-like timbre of 12-string tenor guitar to tug at the soul as much as his beseeching voice.

The quaint but complex folk instrumental Sunrise on the Mississippi conjured up a sense of place, though he packed more of an emotional hit with The Whole Night Sky and generated a spontaneous call-and-response from the audience on Wondering Where the Lions Are.

Overall, this was a sober affair but, ever mindful of the mood, he decided not to end on one of his “ain’t life crap” songs, choosing to bow out with the more spiritually nourishing Mystery instead.

Show date: October 6, 2015

September 19, 2015

Calgary Mayor, Naheed Nenshi

The Canada We Hope For - Mayor Nenshi's speech

On September 19, 2015, Mayor Naheed Nenshi presented at the LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium hosted by the Institute for Canadian Citizenship and its co-founders and co-chairs, John Ralston Saul and the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson. It is an annual signature event hosted across the country, showcasing leading thinkers. An adapted version of the speech appears in today's Globe and Mail and the portions of the speech (plus interview) ran on CBC's Ideas.The full video of the speech can be viewed below or through this link.

The following is the full text of Mayor Nenshi's speech: “The Canada We Hope For: A Naïve View”.

[Thank you and good morning. It truly is a great honour for me to be with you today. I’m honestly a bit surprised to be here. When I was a volunteer helping organize George Elliot Clarke’s lecture in 2006, when I proudly carried quotes from His Highness the Aga Khan’s 2010 lecture on my phone (they’re still there), when I tried to understand all the big words in John Ralston Saul’s inaugural lecture, I never thought I’d be in the company of these artists, these intellectuals, these people who’ve changed the world. I’m just a kid from East Calgary who likes to share stories. And I will do that today, in the hopes that the stories may help us better understand this place we call Canada and the roles we all have in this play we’re writing together.]

I bring you greetings today from a place called Moh’kinsstis—the Elbow, a place where two great rivers meet. It’s the traditional land of the of the Blackfoot people, shared by the Beaver people of the Tsuu T’ina Nation and the Nakota people of the Stoney Nations, a place where we walk in the footprints of the Metis people.

The Blackfoot people have honoured me with the name A’paistootsiipsii, meaning “Clan Leader: the one that moves camp while the others follow”. It is a name that humbles me. And it reminds me of the humbling responsibility I have every day.

It is an honour to be with you here today, in this time of reconciliation, on the traditional lands of the the Huron-Wendat, the Hodnohshoneh and the Anishnabe. We are not on new land newly populated. We are on ancient land that has been the source of life for many people for thousands of years. For more than 5,000 years, people have lived, hunted, fished, met, and traded here. People have fought and loved—held fast to dreams and felt bitter disappointment.

This is part of our collective history—a reminder that we are all treaty people. And our common future is one of opportunity for all.

Today, I’m going to tell some stories. Some are personal, some have nothing to do with me. But I believe in the power of stories to help us better understand who we are, and crucially, who we want to be.

So, please allow me to indulge in some origin stories, beginning with my own.

My parents came to this country in 1971 when my mother was pregnant with me. I was therefore, born in Canada, but made in Tanzania.

This summer, I went on a family trip. I took my mother and my sister’s family, and we all went back to Tanzania. Our little group ranged in age from six to 75, and we were exploring our roots. We saw the house my mum grew up in and the hospital where my sister was born and lots of elephants. But, more important, we reflected on our own roots. I stood on the shores of Lake Victoria in Mwanza and gazed across the lake. I realized that, if my parents had been born on the other side, instead of being immigrants in 1971 they would have been refugees in 1972.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. In the early 1970s, my parents were working in a place called Arusha. Then, as now, Arusha was used for many international and UN meetings. My dad met some Canadians working for the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). They used to get the Toronto Star delivered to them, and dad, a voracious reader, used to ask for the newspaper when they were done with it. So he read, and he learned all about this strange place.

One day, he read an article about the new city hall in Toronto. As he saw the pictures of that great building and Nathan Phillips Square, he was amazed. How do you build such a tall building, he wondered, and make it round? He resolved that, one day, he would see that city hall.

A few years later, he got his chance. He had saved up so he could go to his sister’s wedding in London, England. He figured that, since he was in London, he might as well make a side trip to Toronto (I’m not sure he consulted a map). Just before leaving, they discovered my mum was pregnant and decided to go anyway, leaving my three-year-old sister with relatives. Much to my regret, they did eventually send for her.

When they got to Toronto, they immediately fell in love with the place (it was summer). They felt a certain freedom, like their kids could do anything there, and they decided to stay.

What followed was a very ordinary story familiar to so many of us.

When my parents arrived, there were six Ismaili families in Toronto and they did prayer services at someone’s home. On Fridays, my mother would strip her only bed sheets off the bed, wash them by hand, hang them to dry (there was no nickel for the dryer), and hope they would be done in time to fold, take on the subway, and bring to evening services so there would be a decent cloth to cover the small tables and lend some dignity to the basement.

Only a few months later, this little group of six families found themselves having to look after hundreds of Ismaili families—refugees from Uganda—and show them how to make it in this strange new place. They never once begrudged this. Even though they had so little, these new arrivals had even less.

Even though my parents barely knew how to navigate Canada, the newcomers had no idea. So they got to work. It was the right thing to do.

When I was a year old, having done my research and crafted a thorough argument, I convinced the family that our future was in the west, and we packed up a Dodge Dart and moved to Calgary. Sometimes we were very poor. Sometimes we were only mostly poor.

But what we lacked in money, we gained in opportunity. I went to amazing public schools. I spent my Saturday afternoons at the public library. I learned to swim, kind of, at a public pool. I explored the city I love on public transit. And through it all, I was nurtured by a community that wanted me to succeed, that had a stake in me, and that cared about me.

And in 2010, 20 months before he died, my dad, who loved Toronto City Hall, got to sit in another city hall and watch his son be sworn in as mayor.

While that story may seem extraordinary in its details, what’s extraordinary is just how ordinary it is. It is a very Canadian story. It is a story of struggle, service, sweat and, ultimately, success.

Almost every Canadian has such an origin story and every one is worth telling. And with each telling, we share in the story of who we are.

There is another origin story that touches my people—Calgarians—very deeply. This Canadian story reaches back even before the origin story of Lafontaine and Baldwin.

It is the story of Treaty 7. Actually, it’s the story about the story of Treaty 7.

A few years ago, a small group of visionary artists, historians, and cultural leaders came together to create a theatrical presentation about the creation of Treaty 7. With over 20 First Nation and non-Aboriginal performers, it would explore the historical and cultural significance of the events at Blackfoot Crossing in 1877.

The resulting production, Making Treaty 7, is the origin story of my people.

That may sound a bit odd. I’m not that kind of Indian, after all. How can I find my origin in the story of people who signed a treaty while my ancestors were a world away?

But that’s the point.

This beautiful and funny and sad and inspiring and painful work of art reminded us that we are all treaty people. All of us who share this land. It’s our origin story.

Certainly, it hurts at times to think about what we’ve lost. But it’s elating to think about what we’ve gained.

The story doesn’t end there though. It continues through unbearable tragedy and emerges in triumph.

A few months after the performance, and after I was granted my Blackfoot name, two of the creators of Making Treaty 7, Narcisse Blood and Michael Green (Elk Shadow) went to Saskatchewan to help the people there understand their origin story—Making Treaty 5. And then, on their way to the Piapot First Nation, on Highway 6, with two Saskatchewan artists, Michele Sereda and Lacy Morin-Desjarlais, they were killed in a terrible car accident.

That night, as news spread, one after the other, Calgary buildings and roads and bridges lit up in yellow to honour Michael’s artistic home, One Yellow Rabbit Performance Theatre. No one organized it—it just happened. It was the right thing to do. Michael’s memorial service was held in a packed concert hall—the same place that had hosted the memorial for a much-loved former mayor and premier just a year earlier.

And, of course, the stories continue to be told. On January 7, One Yellow Rabbit will open the 30th Annual High Performance Rodeo. And, on Wednesday, Making Treaty 7 will remount as one of the first shows in a brand-new concert hall, reminding us again that we are all treaty people.

So far, I have only told you origin stories. I have told you two Indian stories, and they show us what we love about Canada and what we hope Canada was and will continue to be.

They tell us about when Canada works.

And when Canada works, it works better than anywhere.

What we know is that the core strength of our community is not that there are carbon atoms in the ground in parts of this country and maple trees with amazing sap in others.

What we know is that we’ve figured out a simple truth—one which evades too many in this broken world. And that simple truth is just this: nous sommes ici ensemble. We’re in this together. Our neighbour’s strength is our strength; the success of any one of us is the success of every one of us. And, more important, the failure of any one of us is the failure of every one of us.

This means that our success is in that tolerance, that respect for pluralism, that generous sharing of opportunity with everyone, that innate sense that every single one of us, regardless of where we come from, regardless of what we look like, regardless of how we worship, regardless of whom we love, that every single one us deserves the chance right here, right now, to live a great Canadian life.

But this is incredibly fragile. It must be protected always from the voices of intolerance, the voices of divisiveness, the voices of small mindedness, and the voices of hatred. It’s the right thing to do.

As that great Canadian philosopher, Bruce Cockburn, reminds us “nothing worth having comes without some kind of fight/Got to kick at the darkness 'til it bleeds daylight.”

And our fight is for that Canada.

And I worry that, in our current public and political discourse, we are losing that fight.

Let’s talk about Bill C-24.

One of the highlights of my time as mayor is being able to go to citizenship ceremonies. Every time, without fail, I cry. I cry with joy to be with so many people to have chosen to be Canadian. They have worked so hard to be a citizen (in the formal sense of the term). They have taken on the great responsibility of being a Canadian. And I weep as I share in that special moment, talking about how growing up, I always wondered why my family all had these fancy citizenship certificates and all I had was a lousy birth certificate.

As I grew up, I realized that those pieces of paper were not only the most valuable possessions we had, but that they were really the same.

No longer.

How is it that those individuals I get to watch saying their oath should somehow be less Canadian than others? How is it that we should allow it to be easier for our government to strip them of that privilege and responsibility of citizenship?

How is it that I, born at Saint Mike’s in downtown Toronto, could be stripped of my Canadian citizenship? How did we let this happen?

(An aside: two weeks ago, when asked about my concerns about this, a spokesperson for Minister Chris Alexander said “As for his views on our strengthened citizenship laws, unless he [Nenshi] intends to commit and be convicted by a Canadian court of acts of terrorism, treason, espionage or taking up arms against the Canadian military, he has nothing to worry about.” Not only does this person spectacularly miss the point, she doesn’t even know what the act that her boss is responsible for actually says. As Prime Minister Harper likes to say, look, let me be clear: either you believe in the rule of law in Canada, or you don’t.

One Canadian citizen committing the same crime should be treated the same as any other citizen, not subjected to a different sort of justice if they had a parent or grandparent who was born somewhere else. And the bill allows her boss to exile people from Canada without any Canadian court being involved. I suspect Canadians don’t really want him to have that authority.)

How did we get here?

I am deeply troubled at the language of divisiveness we hear in Ottawa these days. The label of “terrorist” is thrown around with disturbing regularity. But it is not done haphazardly. It is targeted language that nearly always describes an act of violence done by someone who shares my own faith.

The man who murdered Edmonton Constable Daniel Woodall was, we are told, a very unwell, dangerous man. The man who ran over two soldiers in Quebec was a “radicalized” terrorist. According to our Prime Minister, one of our greatest threats is of “Jihadi terrorism.” Well, sometimes he says “jihadist terrorism.” He generally avoids saying “Islamist terrorism” these days, so I guess there are small blessings.

But this is very specific, very deliberate language. It ties violent action to a religious group—many of whom are Canadian citizens. It does little to understand the causes of violence or the potential solutions. Instead, it encourages division; the opposite of the Canada to which we aspire.

The ridiculous debate on the niqab at citizenship ceremonies is another example. On the one hand, our government warns us of the radicalization of Muslim youth in our own communities. Law enforcement officers and community activists have repeatedly warned us that the cause of this radicalization is alienation and isolation; that the kids being radicialized are the same kids who join gangs. It truly is not about religion. So, we work hard to make these kids feel part of the community.

But then, on the other hand, in order to give a sop to some elements in our society, the government picks a fight on a completely irrelevant issue. So the government announces it will appeal two court decisions (an unwinnable appeal if I’ve ever seen one) and spend millions of dollars of taxpayer money, to prevent one woman from voting.

And those kids—the ones we are trying to convince that there’s a place for them in our society—are told that no matter what, they can never be truly Canadian. That their faith is incompatible with our values. All that good work on de-radicalization? Completely undermined by our own actions.

When we act like this, whether the issue is dealing with the extraordinary human suffering of those fleeing conflict or the right to vote, we are failing ourselves, our nation, and the world. It’s the wrong thing to do.

And I’m serious when I say “the world”. Canada, the idea of Canada, is a powerful beacon for all humanity. But here again, I fear we are failing.

The government has been running commercials that end with the slogan, “Strong. Proud. Free.” (Who knew that countries have slogans). The Economist last week called us “strong, proud and free-riding.” A study by former CIDA president Robert Greenhill and Meg McQuillian indicates that our foreign aid performance from 2008-2014 ranks us dead last in the G7.

In a recent interview, Mr. Greenhill suggests that that if spending had stayed at 1979 levels and the money been used to help destabilized countries, hundreds of thousands fewer people might now be fleeing, and thousands fewer dying.

And it’s important to note that this is not a partisan argument. Our commitment to assisting in global poverty began to flag in 1995 and has largely continued for 20 years, under Liberal and Conservative governments.

My friend John McArthur tells a story about a recent debate. December 2013 marked the multi-year replenishment deadline for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria—one of the world’s most successful modern life-saving institutions. Months earlier, the United States and the United Kingdom had made their own anchor pledges. They also offered matching grants to help motivate other countries’ contributions. Nations such as Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden each stepped in with commitments equivalent to $8 to $10 per citizen, per year. Canada, by contrast, left its decision to the final moment. After a flurry of last-minute internal deliberations, the government committed less than $220 million per year, or only $6 per Canadian. The lowball pledges from Canada and a few other countries meant that hundreds of millions in matching dollars were left on the table and the Global Fund suffered a billion-dollar annual shortfall. That billion-dollar shortfall will cost one million lives. And we bear too much of that responsibility.

The shocking part of all of this is not that it happened, but that we collectively did not notice. It was as though we had stopped thinking about the world around us and about our role as leaders.

Former Prime Minister Joe Clark warned in 2013 that we were gradually turning inward, writing:

"An essential question for citizens of lucky countries is not simply who we are or what we earn, but what we could be. That question implies others: To what do we aspire? What are our talents and advantages and assets? How can we be better than we have been, in our impact on events both inside and outside our country?"

I say we aspire to a better Canada in a better world, and that we have that power as citizens to make it happen. It’s the right thing to do.

In just a few days, while those kids are performing Making Treaty 7 in Calgary, we will be witness on the other side of the continent to the largest gathering of world leaders in history.

Those leaders will adopt a new series of Sustainable Development Goals—the Global Goals. They will commit to an extraordinary vision: a vision of a world free of poverty, hunger, disease, and want. A world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity. A world of equal opportunity permitting the full realization of human potential.

There are 17 goals, 107 outcome targets, and 62 targets for implementation. And we have to do it by 2030.

So what, then, is our role as Canadians? We must take on the challenge given us as lucky citizens. It’s the right thing to do.

I’m speaking as though these failures of the Canada to which we aspire are recent. They’re not. I’m naïve, but I’m not that naïve.

After all, we are the nation of Japanese internment camps. We are the nation of the Chinese head tax and Africville. We are the nation of Komagata Maru and provincial eugenics programs. We are the nation of “none is too many.” We are the nation that created and sustained residential schools.

These are our stories too. They are not lapses in our citizenship. They are not moments when we temporarily forgot what it was to be Canadian. They are real and they are stories we tell—as uncomfortable as we are in the telling.

We feel a deep, cold, dark discomfort when confronted with those stories of ourselves. The truth is not easy. It wasn’t easy for the victims of residential schools to tell their stories to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It wasn’t easy for Canadians to bear witness to those stories. But it is profoundly important that we did and that we do.

But there’s something noble in this.

We cannot shy away from these stories of divisiveness.

In telling those stories alongside our origin stories, we move forward.

But there is also something noble and true and real and perfect and Canadian in the stories that we tell that inform us about who we want to be. The stories of the best Canada. The stories of the Canada to which we aspire.

They allow us to proudly say to the world who we are and what it means to be Canadian. They are stories of ideas and, more important, they are stories of actions. Because the best stories are stories of action. Stories of everyday people using their everyday hands and their everyday voices to make extraordinary change. Because it’s the right thing to do.

Let’s start with us—our actions as individuals.

When I first became mayor, I pulled together a group of super-volunteers and gave them what I thought was a simple task: figure out a way to get more people involved in the community and report back in 30 days. Forty-five days later, they came back and said “great news, mayor! We’ve come up with a name for our committee!” They could not have done worse. The Mayor’s Committee on Civic Engagement. (They’ve since changed it, I kid you not, to “The Mayor’s Civic Engagement Committee.”)

A few days after that, they came to me with a simple idea: Three Things for Calgary. A social movement that encourages every citizen, every year, to do at least three things for their community. Three things, big or small.

I thought this idea was crazy. It’s paradoxically too simple and too complex, I said. It’s too simple because we’re not telling people what to do. I’m a researcher, and I know the research shows that the number one reason people don’t volunteer is “nobody asked me.” We have to match people with non-profits. We have to give them ideas.

It’s too complicated because we want to lower the barriers. Why ask people to do three things instead of one small thing?

I was wrong.

It turns out the weaknesses I saw were the strengths of the idea. In not telling people what to do, we allowed them to answer two questions for themselves: What do I care about? What am I good at? It’s at the nexus of these two things that people figure out the right thing to do.

And they do things I would never have thought of. Like the mum who had the terrifying experience of rushing her child to the children’s hospital and spending the night in the emergency room. She didn’t get any sleep, of course, and felt awful in the morning as she took her daughter to various tests and appointments.

When they were all safely at home, she reflected on the experience. And now, every year, she conducts a toothbrush drive for the Alberta Children’s Hospital ER. Not kids’ toothbrushes—adult ones. This is so that parents, having gone through the scariest night of their lives, can brush their teeth in the morning and feel just a little more human. And as they brush their teeth, they are reminded that they live in a community that cares about them—that has a stake in them. For that mum, it was the right thing to do.

And, of course, it’s not really about doing three things every year. It’s about setting up an expectation for a lifetime of service. It’s about creating a habit of service. It’s about internalizing the right thing to do and doing it.

And that habit manifests itself every day in a million little ways. This was never on display as much as during our community’s greatest challenge: the 2013 floods. I won’t dwell on the crisis—that’s a whole other speech—but I’ll share a couple of, you guessed it, stories.

Very early on during the flooding, we were inundated with people asking simply, “how can I help?” We weren’t quite sure what to do, and eventually invited everyone who wanted to assist with the cleanup to meet one morning at McMahon Stadium. My colleagues at the City of Calgary didn’t give much notice—just a couple of hours. When I asked why, they said “well, your worship, we don’t really know what we’re doing. We figure that if we keep this low-key, only a hundred or 200 people will come, we’ll figure out what we’re doing and be ready for more tomorrow.”

I was skeptical, but I went to the stadium to meet the few volunteers I expected. You’ve probably seen the pictures. I was greeted by thousands of people—some in work boots and some in flip-flops—united only in their desire to help strangers in their community.

There was no PA system. I climbed up on a folding table, reached into the driver’s side window of a fire vehicle, and used the radio attached to the sirens. My city colleague yelled up at me, “Send them home! We’ve run out of forms!”

I took a deep breath, visions of municipal lawyers danced before my eyes, and I said “We’ve run out of forms. There’s no more room on the buses. But you’re here to help. Just go help. You know what neighbourhoods have been badly hit. Just go. You may have to go door to door, but it will probably be clear what to do. Just go.”

And they went. And they went. And they went. In the hundreds and thousands, they went. The largest outpouring of humanity I have ever seen. Not organized, driven only by the very real, the very Canadian, desire to help. Because it was the right thing to do.

I got into a habit during the flood of just taking quiet walks in the flood-impacted neighbourhoods. If I could steal away from the emergency operations centre for an hour, I would. No fanfare, just a chance to talk to people about what had happened and how they were coping.

On one of those walks, on a quiet street in Rideau/Roxboro, just down from the Mission Bridge, I met Sam and his mum, Lori. They were kind enough to invite me into their home, or what was left of it. Everything was gone; it was stripped down to the studs.

“We’ve had a tough few days,” she said. “There’s nothing left in my house. I have no stove, no fridge, no cabinets. I have no way to prepare meals for my family. But you know what, Mayor? Tonight, for dinner we have hot shepherd’s pie.”

I often think about that shepherd’s pie. When I’m having a bad day, I think of the anonymous hands that made it. The hands that boiled the potatoes and peeled them, that mashed them and turned the mixture into a casserole dish and covered it tightly in foil. The person who stopped and thought: “I’m never going to see my casserole dish again. But you know what, it doesn’t matter. Somewhere out there, there’s a family that hasn’t had a hot meal in days, and they have to get this shepherd’s pie while it’s hot. It’s the right thing to do.”

I think of Bev. Bev, like so many others in Calgary, went to help a friend. Then she helped the friend’s neighbour, and the neighbour’s neighbour. One day, she found herself in a stranger’s basement and she saw the one thing that finally knocked her to her knees. It was a beautiful photo album—“Our Baby”—and it was ruined.

She stopped short, and she thought: “We can replace people’s furniture. We can replace their appliances and their flooring and their drywall. But how do we replace their memories?”

And she made a decision. Bev has a hobby. She’s a quilter. And she decided that she would make a quilt. She would make it good, and she would make it strong. And she would give it to a family that had lost everything.

And they would make blanket forts with it. And they would curl up under it to watch a movie on cold nights. And the kids would want it when they left home.

And that one family would have a new heirloom and create new memories.

Word spread about Bev’s project. People started talking; they wanted to help. A group of senior ladies wanted to help, but didn’t have any materials. Someone organized a small fundraiser and got scraps of fabric and cotton batting.

I had no idea any of this was happening until I got a call in September. They were going to distribute the quilts, door-to-door in the flooded areas. Could I please come and say thank you to the volunteers?

So, on a sunny and crisp autumn Saturday morning, I went to the Inglewood Community Hall to see 1400 quilts.

They had come, not just from a few senior citizens in Calgary, but from across Canada and the world—as far away as Brazil. And every one of them had a card attached. “In this difficult time, please know that you are part of a community.”

It was the right thing to do.

And my dream for Canada, my dream for this nation in the world, is that simple. That we do the right thing.

Can you imagine if for 2017, for the sesquicentennial of this great nation, we give Canada a birthday gift? Can you imagine if Canada gives the world a birthday gift? Can you imagine Three Things for Canada? Let’s make the commitment today to each do three things for our country, for the world, starting now and continuing through our 150th birthday. Showing everyone the right things to do.

But the real answer in crafting an ideal Canada—the Canada to which we aspire—lies in engaging muscularly with the past and the future. It means a thousand simple acts of service and a million tiny acts of heroism. It means acting at the community level: on our streets, in our neighbourhoods, and in our schools. It means refusing to accept the politics of fear.

And then it means exporting the very best of Canada, that ideal and real Canada, to the rest of the world.

I want to leave you with one last story. One I tell all the time. One that I will keep telling, since it encapsulates who we are and who we aspire to be.

I had the chance a couple of years ago to visit the 100th Anniversary of a school in Calgary. It’s called Connaught School, named after the Duke of Connaught—the Governor General of Canada, the son of Queen Victoria.

Now, the population of the school looks different than when it first opened. Because it’s right downtown, it’s often the first point of arrival for newcomers to Canada. There are 240 students. They come from 61 different countries. They speak 42 different languages at home.

I spoke to some of those kids and their parents. I heard horrible things. I heard stories of war and unspeakable poverty. I heard stories of degradation and loss of dignity. I heard stories of violence so horrific I could not imagine one human being doing that to another, let alone in front of a child.

I looked out at those kids, sitting on the floor in the gym, wearing their matching t-shirts celebrating their school’s birthday.

I looked beyond them, at their parents, in hijabs and kanga cloth, in Tim Hortons uniforms and bus driver caps, in designer suits and pumps.

At that moment, it would have been so easy to feel despair, to mourn for our broken world.

But I didn’t.

Because in that second, I had a moment of extraordinary clarity. I knew something to be true beyond all else.

I knew that regardless of what these kids had been through, regardless of how little they have or had, regardless of what wrath some vengeful God had visited on them and their families, they had one burst of extraordinary luck.

And that luck was that they ended up here.

They ended up in Canada, they ended up in Calgary, they ended up at Connaught School. They ended up in a community. They ended up with people who would catch them if they fell. They ended up in a community that wants them to succeed, that has a stake in them, that cares about them.

And I knew at that moment, that those kids, right here, right now, would live a great Canadian life.

That’s the promise of our community. That’s what I have the humbling responsibility to make real every day.

And that’s the opportunity you have. Because it’s the right thing to do.

September 15, 2015

Canadians.org

[Woodpile editor's note: Bruce is among many who signed the Leap Manifesto]

Leap manifesto: bold climate and economic vision for Canada

by Andrea Harden-Donahue

We could live in a country powered entirely by truly just renewable energy, woven together by accessible public transit, in which the jobs and opportunities of this transition are designed to systematically eliminate racial and gender inequality. Caring for one another and caring for the planet could be the economy’s fastest growing sectors. Many more people could have higher wage jobs with fewer work hours, leaving us ample time to enjoy our loved ones and flourish in our communities.

Canada is not this place today – but it could be.

These are the inspiring words of the leap manifesto, a bold 15 point vision for Canada, launching today. Maude Barlow will be one of several high profile speakers alongside David Suzuki, Naomi Klein, Stephen Lewis, Tantoo Cardinal (and more) attending a press conference at the Toronto Film Festival for the manifesto.

You can read, and sign the manifesto at www.leapmanifesto.org, download a useful graphic outlining the 15 demands and supporting research paper from the Canadian Centre of Policy Alternatives on why we can 'afford to leap.'

Here are the manifesto's 15 demands.

- The leap must begin by respecting the inherent rights and title of the original caretakers of this land, starting by fully implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- The latest research shows we could get 100% of our electricity from renewable resources within two decades; by 2050 we could have a 100% clean economy. We demand that this shift begin now.

- No new infrastructure projects that lock us into increased extraction decades into the future. The new iron law of energy development must be: if you wouldn’t want it in your backyard, then it doesn’t belong in anyone’s backyard.

- The time for energy democracy has come: wherever possible, communities should collectively control new clean energy systems. Indigenous Peoples and others on the frontlines of polluting industrial activity should be first to receive public support for their own clean energy projects.

- We want a universal program to build and retrofit energy efficient housing, ensuring that the lowest income communities will benefit first.

- We want high-speed rail powered by just renewables and affordable public transit to unite every community in this country – in place of more cars, pipelines and exploding trains that endanger and divide us.

- We want training and resources for workers in carbon-intensive jobs, ensuring they are fully able to participate in the clean energy economy.

- We need to invest in our decaying public infrastructure so that it can withstand increasingly frequent extreme weather events.

- We must develop a more localized and ecologically-based agricultural system to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, absorb shocks in the global supply – and produce healthier and more affordable food for everyone.

- We call for an end to all trade deals that interfere with our attempts to rebuild local economies, regulate corporations and stop damaging extractive projects.

- We demand immigration status and full protection for all workers. Canadians can begin to rebalance the scales of climate justice by welcoming refugees and migrants seeking safety and a better life.

- We must expand those sectors that are already low-carbon: caregiving, teaching, social work, the arts and public-interest media. A national childcare program is long past due.

- Since so much of the labour of caretaking – whether of people or the planet – is currently unpaid and often performed by women, we call for a vigorous debate about the introduction of a universal basic annual income.

- We declare that “austerity” is a fossilized form of thinking that has become a threat to life on earth. The money we need to pay for this great transformation is available — we just need the right policies to release it. An end to fossil fuel subsidies. Financial transaction taxes. Increased resource royalties. Higher income taxes on corporations and wealthy people. A progressive carbon tax. Cuts to military spending.

- We must work swiftly towards a system in which every vote counts and corporate money is removed from political campaigns.

This transformation is our sacred duty to those this country harmed in the past, to those suffering needlessly in the present, and to all who have a right to a bright and safe future.

Now is the time for boldness.

Now is the time to leap.

September 12, 2015

D. Keebler

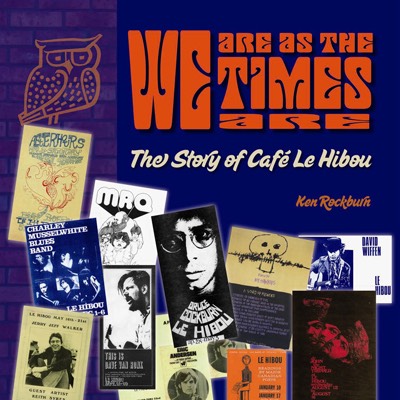

We Are as the Times Are

Ken Rockburn's book regarding the history of the famed Ottawa music venue, Le Hibou, can be purchsed here. Bruce played many a show at Le Hibou in the 1960s and early 1970s.

More online info can be found at Denis Faulkner's website. He was the founder and first owner of the venue from October 1960 to December 1968.

September 11, 2015

The Ottawa Citizen

Coffeehouse nights: New book remembers Le Hibou

Review by Parick Langston

Book review: We Are as the Times Are

By Ken Rockburn

In town: The author will launch his book at Irene’s on Bank Street on Sept. 14, 2015.

Ken Rockburn’s many nights at Café Le Hibou, the legendary Ottawa coffeehouse that between 1960 and 1975 showcased an extraordinary lineup of musicians and other artists, included one which left him bemused.

The veteran broadcast journalist and author of the newly published We Are as the Times Are: The Story of Café Le Hibou recalls being 16 and squiring an attractive young lady to the coffeehouse for a concert by American blues great John Hammond. After his first set, Hammond made a beeline for the couple’s table and started chatting up Rockburn’s date.

Says Rockburn: “I’m sitting there thinking, ‘Am I pissed because John Hammond is hitting on my date or am I in awe because John Hammond is sitting at my table?’ I chose the latter.”

Le Hibou was, in other words, a spot where expectations might be rattled, where almost anything could happen thanks to a cavalcade of culture that included not just nervy performers like Hammond and the voodoo-influenced Dr. John the Night Tripper and the up-and-coming Gordon Lightfoot but also poetry readings (by Irving Layton among others), theatre (including Too Many Guys For One Doll, an original musical satire on municipal affairs and then-Ottawa mayor Charlotte Whitton), film (English and French), and dance (including a lecture and demonstration of modern dance by the now-renowned Elizabeth Langley).

With entertainment options few and far between, “People saw Hibou as this kind of oasis where things were happening outside their (life) in Alta Vista,” according to Rockburn who’s known for his work with Cable Public Affairs Channel (CPAC), CBC, and others.

The idea for his comprehensive, highly readable book, which he launches Sept. 14 at Irene’s Pub, came from Rockburn’s friend Paul Kyba. Realizing that all the former owners of the coffeehouse were still living, Rockburn set out to record the memories before it was too late.

The memories include those of Denis Faulkner. A University of Ottawa student at the time, he co-founded with three others the coffeehouse at its first location above a Rideau Street chiropractor’s office just east of Coburg Street. Faulkner says he had no inkling at the time that “a little place for people to meet and talk and have good coffee and listen to folk singers or flamenco would morph into an almost-iconic institution.”

Just how iconic is clear from Faulkner’s website Café Le Hibou Recollections (lehibou.ca). In addition to a history of the place and a comprehensive list of its 15 years of bookings, the website includes a slew of recollections from fans. Those memories range from a first date at the club that blossomed into marriage to a posting from someone who says hanging around Le Hibou transformed him from a respectable student with good grades to a grungy guy barely eking out a pass but who, in retrospect, “wouldn’t trade those days for anything.”

Such heartfelt posts, says Faulkner, prove that not just the club with its red checked tablecloths and candle-stuffed Chianti bottles but the entire era was meaningful to many. “It was a remarkable time. It was the 1960s; the future was wide open.”

Judging from the performers, it was an inclusive future at Le Hibou. Folk singers Judy Collins and Murray McLauchlan played there as did bluesmen Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. So did jazz guitarist Lenny Breau. Ditto a nascent Neil Young.

A very young Joni Mitchell landed a three-week gig for $150 a week in 1967. While there, reports Rockburn, she hooked up with musician Bill Stevenson, and the two dropped acid in Strathcona Park.

Rockburn also quite rightly dedicates considerable space to poet/songwriter William (Bill) Hawkins. He was a regular at Le Hibou and a member, along with Bruce Cockburn, Sneezy Waters and others, of the Ottawa band the Children which played the venue. A troubled man from whose poem Gnostic Serenade the title of Rockburn’s book – We Are as the Times Are – is taken, Hawkins was, says Rockburn, “an intellectual magnet” in Ottawa’s counterculture scene. But substance abuse sapped his creative drive, and Hawkins vanished from the scene in 1974 to drive a cab for years before finally re-emerging with new music and poetry. It’s an especially poignant section of the book.

Le Hibou was also a locus of live theatre for several years. Saul Rubinek, Luba Goy and others performed at the club after it moved to Bank Street in 1961 and after its final move to Sussex Drive just over three years later. Productions were eclectic, from original pieces to John Webster’s 17th century tragedy The Duchess of Malfi.

None of which made the owners wealthy. “I never intended it to be, but it was non-profit,” says music promoter and former Treble Clef music store owner Harvey Glatt. He was a partner in Le Hibou from 1961 to 1968 and booked the music acts.

Glatt also recalls the respect paid to performers. “It was very important that people be quiet; if they weren’t, we’d ask them to leave.”

Sneezy Waters, whose first gig at Le Hibou was in that show about Charlotte Whitton, recalls the community-building aspect of Le Hibou. “It wasn’t a drug den or a bar. For me, it was like a library: you’d go to learn something.”

Waters was also there when Le Hibou closed in the spring of 1975. It was the victim, as Rockburn details, of everything from increased competition from licensed clubs (Le Hibou was basically dry) to the coup de grace: a leap in rent at the National Capital Commission-owned Sussex Street address from $450 a month to $2,000.

“I was there on the last day,” says Waters. “There was gnashing of teeth and wailing and a pretty heavy sadness. There were people on the street looking through the windows. It was hard to imagine it would be gone.

A Le Hibou timeline

October, 1960: Café Le Hibou opens at 544 Rideau St. Owners: Denis Faulkner, Andre Jodouin, Jean Carriere and George Gordon-Lennox. It serves coffee and light food, and hosts poetry readings and occasional impromptu concerts.

October, 1961: The club moves to 248 Bank St. and hires its first paid entertainer: local folk singer Tom Kines.

February, 1965: Le Hibou moves to its final home at 521 Sussex Dr., a heritage building with a 15-foot, stamped tin ceiling.

June, 1965: Gordon Lightfoot, who had not yet released his debut album, plays the first of several dates.

November, 1968: John Russow, the coffeehouse’s night manager, and his wife Joan buy Le Hibou.

June, 1968: Newly sworn-in prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau pays a late-night visit to Le Hibou accompanied by his chauffeur and a single bodyguard. He misses the show but signs a poster.

October, 1969: Van Morrison and his “jazz rock band” play a multi-night gig.

Spring, 1972: Pierre Paul Lafreniere, the final owner, buys the club.

May 3, 1975: Le Hibou closes.

Sources: Denis Faulkner, Ken Rockburn, lehibou.ca

September 11, 2015

The Star

Al Purdy Was Here exposes Canada’s cultural roots

by Martin Knelman

Al Purdy Was Here, Brian D. Johnson’s documentary about the deceased, highly combative Canadian poet, is not only one of the engaging treats in this year’s TIFF Docs program; it’s multi-dimensional.

Part warts-and-all investigation of how a rebel poet created his own myth and part total-pleasure songbook, the film will have its world premiere on Tuesday, Sept 15 at TIFF Bell Lightbox. And 15 years after his death, this should remind a lot of people that Al Purdy was indeed here.

From the perspective of fall 2015, this is not just nostalgia but a timely reminder of those golden pre-Harper years decades ago when culture played a key role in Canadian nation-building, and poets led the charge.

Just as striking for many is the emergence of Johnson, best known for more than two decades as the film critic at Maclean’s, as a hot director.

No one is more surprised — almost apologetic — than Johnson himself.

“I know this sort of looks like a man-bites-dog case about a long-time film critic deciding to reverse engines,” he told me one recent evening at a Yorkville cafe.

True, he had retired from Maclean’s in early 2014 and had time to do something completely different.

“But it wasn’t a career choice. I got pulled into this thing gradually and before that I didn’t know a thing about Al Purdy.”

It was Marni Jackson, the talented author, who lured her husband into this project, one chapter at a time.

“Marni had interviewed Purdy and she had written about him,” says Johnson. “I owe the film to her.”

Jackson knew all about the legendary A-frame cabin that the back-to-the-land poet and his wife, Eurithe, had built out of discarded lumber in Ameliasburgh. That’s in Prince Edward County, which later became a high-end rural favourite of Ontario’s social elite.

Indeed, Eurithe, at 90, emerges now as one of the great strengths of the new film, with sheer star quality. Terrific songs and a surprise Act 3 plot turn are the other ingredients that make this a breakthrough not just for Purdy followers but for many who know little or nothing about the poet.

Along the way we get performances by Bruce Cockburn, Tanya Tagaq and Sarah Harmer, as well as insights from Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje and Leonard Cohen.

“Marni was well down the Purdy road,” Johnson says. She worked on a 2013 event at Koerner Hall: a fundraiser to restore the A-frame house and keep it going as a mecca for writers, while raising money to maintain a poet-in-residence program there.

The event was filmed and Jackson asked Johnson to edit the footage.

“I found this guy enchanting and charismatic,” he recalls. He was also boisterous and an entertaining raconteur.

But there were many sides to this hard-drinking, high-school dropout who hopped a freight train, heading west during the Depression, and worked in factories before pioneering the idea a guy could earn a living writing poems.

A lot of bad poems came before the good ones, such as his best known work “At the Quinte Hotel,” in which beer drinking looms large. He won the Governor-General’s Award twice.

Songwriters agreed to contribute to the Purdy legend. The obvious next step was a documentary film about this larger-than-life character.

Asked for his advice, Johnson replied that maybe there could be a half-hour for TV.

It was the music that later made him think this should be a full-length documentary. And since he had previously made a seven-minute short film in which other poets read a book by Dennis Lee, Johnson was the right guy to direct this movie.

It was the CBC, through its documentary channel, and film distributor Ron Mann (of Films We Like) that drove the project forward. Now the film is likely to have a limited theatrical release before reaching TV screens in 2016.

For CBC management, this was a great opportunity. The public network was enduring scandal, crisis and cutbacks.

It helped that the team for this film included Jackson as co-writer, Nicholas de Pencier as cinematographer and a young co-producer, Jake Yanowski, who, according to Johnson, wound up mentoring his much older partner.

“This is a tale about Al Purdy and his legacy, but people are bringing more to it,” Johnson told me. “This is about our cultural roots. It evokes nostalgia for a time when poetry mattered, when Canadian culture was still being invented and this activity was a key part of nation-building. Today that seems like a far-fetched ambition for anyone to entertain.”

August 25, 2015

Wicked Local Beverly

MUSIC REVIEW: Bruce Cockburn performs 'gem of a show'

by Blake Maddux

Bruce Cockburn, a 2001 Canadian Music Hall of Fame inductee, treated a general admission audience to gem of a show at The Cabot last Friday night.

Performing a total of 20 songs, Cockburn drew from 14 albums, the best represented of which was 1997’s "The Charity of Night."

If there was a pattern or strategy to his song selection, it was apparent only to him.

Thankfully, this was no mere greatest hits show. In fact, anyone who knew only the contents of the 1979-2002 singles anthology that was available for purchase in the lobby would have been able to sing along to only five songs. And those familiar with the 1970-1979 collection, which was not for sale that night, would have recognized two others.

How ever, a performer as seasoned, versatile, prolific and dependable as Cockburn would have done a disservice to both long-time fans and newcomers -- not to mention himself -- by serving up only the “hits,” which I put in quotes because he has reached the U.S. top 40 only once in his 45-year career.

ever, a performer as seasoned, versatile, prolific and dependable as Cockburn would have done a disservice to both long-time fans and newcomers -- not to mention himself -- by serving up only the “hits,” which I put in quotes because he has reached the U.S. top 40 only once in his 45-year career.

The fact that Cockburn was perfectly free to eschew playing it safe was evidenced by the myriad requests that those in attendance shouted out, as well as the surprising number of times that the audience registered familiarity with a given song immediately after he started plucking his guitar and before he sang a word.

Speaking of the guitar, Cockburn has clearly retained all of what one is justified in calling his virtuoso mastery of the instrument. Having attended the Berklee College of Music in the mid-60s, he is rarely, if ever, satisfied to simply select the few chords that are necessary to accompany his words.

In fact, three of the evening’s numbers were instrumentals, including the first song that he played after taking the stage and the one that opened the second set following the 30-minute intermission.

The first instrumental was “Bohemian 3-Step,” from the 2011 release "Small Source of Comfort," which is Cockburn’s latest album, but one that he acknowledged is “not very recent.”

Before diving into “The Iris of the World,” also from "Small Source of Comfort," he explained that he had spent the time since that album’s release writing an autobiography (titled "Rumors of Glory" after a song from 1980 that he played early in the first set) and being the father of a daughter who is about to turn 4 years old.

Given the time and energy required for those hefty endeavors, he said, there was “nothing left over for songs.” Reassurance that something still remained came in the form of a song that he introduced as a new one, of which he said “there aren’t very many,” but that he was “happy to have any."

This suggested that he remains a devotee of the Christian faith that he has embraced on a personal level for several decades, but from which he has also distanced himself due to his disapproval of the use of Christianity to advance political agendas, with which he disagrees.

I should note that Cockburn did not neglect all of his better-known songs. “Lovers in a Dangerous Time,” which Cockburn released in 1984 and the soon-to-be hugely popular Canadian band Barenaked Ladies covered seven years later, appeared in the first set. He saved the aforementioned lone top-40 entry “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” which prompted a call-and-response sing-along, for the second spot of the two-song encore.

Other crowd-pleasers included “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” and “Call It Democracy,” two politically forthright compositions that he played back-to-back.

Last month, I reviewed a show about which I wrote that two septuagenarians – namely, Brian Wilson and Rodriguez – had set the bar pretty high for all of the younger acts currently on tour. Having turned 70 in May, Cockburn may now join that distinguished company.

Photo by Blake Maddux

August 13, 2015

Philly.com

Bruce Cockburn Accepts His Folk-Hero Status

by Nicole Pensiero

Bruce Cockburn - who will give a solo acoustic performance at 9:05 p.m. Saturday - recalled a time, early in his career, when he would "vehemently deny" he was a folksinger.

"I didn't want to mislead people, and I was fussy about labels like that," said the 70-year-old Canadian-bred, San Francisco-based singer-songwriter. "But if Ani DiFranco's a folksinger, then I guess I am, too."

Cockburn, who last year released his well-received "spiritual memoir" Rumors of Glory, has lasted more than 40 years in the fickle music business, and has dozens of albums - ranging from jazz-influenced rock to worldbeat to, yes, what's probably best termed folk - to show for his efforts.

A word-of-mouth favorite in the United States, Cockburn's something of a national treasure in his native Canada, where his face has adorned postage stamps. (He has also been honored with 13 Juno Awards - the Canadian version of the Grammys - has 21 gold and platinum records, and was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.)

But accolades mean far less to Cockburn than the durability of his music.

"My songs, from an emotional point of view, are like a scrapbook of a place and time," he said. Singing the intense, overtly political "If I Had a Rocket Launcher" from 1984, can be "outright painful." It takes Cockburn back to his state-of-mind at the time he wrote it in response to the appalling conditions at Guatemalan refugee camps. But, Cockburn noted, there are times when performing that very song is "necessary or appropriate," depending on current world events.

"It's part of the process of performing from the heart," he said. And regardless of a song's topic - love, politics, or spiritual connection - Cockburn always welcomes the opportunity to play for his fans, as well as hopefully attract some new ones.

"I like people to listen to what I'm doing," Cockburn said, adding that he also gets to be a music fan himself at outdoor festivals, always discovering "something interesting and new."

This Philadelphia Folk Festival appearance will afford Cockburn the opportunity to sing his best-known songs - like 1979's "Wondering Where the Lions Are" and the haunting "Pacing the Cage" - as well as introduce some new material, "depending on how confident I feel."

August 10, 2015

The Western Star

Cockburn to play two shows at Woody Point literary festival

by Gary Kean

If a tree falls in the Newfoundland forest next month, there’s a chance Bruce Cockburn just might hear it.

The stalwart of the Canadian music scene for the past four decades is coming to Newfoundland and Labrador and plans to drive between shows in St. John’s and Woody Point.

He’s played the capital city before, but this will be his first time venturing outside of St. John’s to play or to take in the scenic landscape.

“I hear there’s a lot of spruce and moose,” he said in a recent interview from San Francisco.

Cockburn’s visit will feature appearances at two folk festivals. He was scheduled to play the 39th annual Newfoundland and Labrador Folk Festival in St. John’s this past Saturday, before trekking to the Writers at Woody Point literary festival.

Cockburn will open the festival with a pair of concerts at the Heritage Theatre in Curzon Village on Tuesday and Wednesday. On the third day, he will be interviewed before a live audience at the theatre by Canadian novelist, essayist and memoirist Lawrence Hill.

His albums have sold more than seven million copies worldwide, but Cockburn has more than his well-known music to discuss. Last November, he released his memoir, “Rumours of Glory,” at the request of publisher HarperCollins.

He said he had been asked to write a book before, but the time just wasn’t right until now.

“We’ve all seen coffee table books about 20-year-old rock stars and 25-year-old hockey stars and stuff like that that say ‘here’s the life of so-and-so, but there’s no life there to talk about really,” he said. “It’s just an excuse to sell people something.”

Cockburn, who was born in 1945, said he didn’t know what the publisher meant when they asked him to pen “a spiritual memoir.” Others have also expressed interest in the background stories of his songs and his life of humanitarian work and advocacy.

The end result is an intimate peek into the inspiration behind all of his work.

“I thought it was worth trying to do the book because there was room in between the songs for a more concrete statement about the kinds of things the songs talk about and about my own life,” he said.

July 9, 2015

Winnipeg Free Press

Excerpted from the article Good Times, Great Music by Melissa Tait & Joe Bryska

Last month, the Free Press sat down with Winnipeg Folk Festival legend Mitch Podolak and asked him to flip through a pile of archival photographs of the event he founded 41 years ago.

"We owe the Winnipeg Folk Festival in a lot of ways to Bruce (Cockburn), because people did not have any idea at all what a folk festival was — none. We knew we had Bruce and we used Bruce in a way we didn’t use anybody else.

"We said, ‘There’s a free Bruce Cockburn concert in the park,’ and 14,000 people showed up the first night to see that, and what they got was the folk festival. Thank you, Bruce."

Photo 1975, David Landry Collection, Archives of Manitoba

July 7, 2015

The Independent

In Conversation With Bruce Cockburn

by Justin Brake

The legendary Canadian singer-songwriter and guitarist talks colonialism, warfare, music as activism and his hopes for the upcoming federal election, in advance of his performance at the Newfoundland and Labrador Folk Festival Saturday in St. John’s.

legendary Canadian singer-songwriter and guitarist talks colonialism, warfare, music as activism and his hopes for the upcoming federal election, in advance of his performance at the Newfoundland and Labrador Folk Festival Saturday in St. John’s.

Few Canadian musicians have earned as much respect and admiration as Bruce Cockburn.

The 70-year-old singer-songwriter has recorded 31 albums and has a lengthy resume of awards for his music and social justice work. He was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1982 and received a Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement in 1998. In 2001 he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, and the following year into the Canadian Broadcast Hall of Fame.

Cockburn has six honorary doctorates, including a 2007 Honorary Doctor of Letters from Memorial University. He also earned a Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012.

He recently married, moved to San Francisco and is raising his three-year-old daughter with his wife.

Pacing the Cage, a documentary film about his life, music and politics, was released in 2013. And last year his memoir, Rumours of Glory, was published by HarperOne.

On Saturday Cockburn will perform at the Newfoundland and Labrador Folk Festival in St. John’s.

In advance of his trip to Newfoundland, he spoke with The Independent from his home in San Francisco about his life, music, activism and politics.

JUSTIN BRAKE: You’re living in San Francisco now. What’s it like living in a state that’s running out of water?

BRUCE COCKBURN: [Laughs] Well, you wouldn’t really notice it in the city. There are parts of the state where it seems to be pretty obvious, but there are also people claiming that it’s not really running out of water — that it’s a scam to raise the price of water. But I’m not sure, I hear a lot more of there actually beig a shortage, and certainly there hasn’t been any rain anywhere, so I think it’s pretty genuine.

Like I said, in San Francisco you don’t really notice it; the city is surrounded by water for one thing, and I think we’re insulated from the effects of the drought. The drought is very noticeable inland, when you go into the central valley where the agriculture is mainly placed, and then it becomes noticeable. And that’s where you hear the largest comments and complaints coming from.

JUSTIN BRAKE: It’s hard to know, when you see produce here in Newfoundland that’s grown in California, whether it’s ethical to buy it or not.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Those farmers still have to make a living, so to the extent that it’s not corporate— [Laughs.] I mean, I’m not sure there’s anything that isn’t corporate, but there are a lot of people out there growing stuff and the industry employs quite a lot of people, so whether the water is running out or not, people still have to grow food. It could be argued that the way the water’s allocated is at times unethical for sure, but there’s also a whole lot of water that gets diverted to L.A….and especially to southern California. But certain elements of the agricultural [industry] seem to use more and have more clout in terms of containing that use than other sections. It’s still all unfolding here. It’s been going on for three years now, this drought, so if it keeps going like this it’ll become way more noticeable I think than it is now.

JUSTIN BRAKE: So how is your life in San Francisco? I know you have a daughter who is three years old. And your wife, who I understand got a job in San Fran—and that’s how you ended up there. What is your life like in California?

BRUCE COCKBURN: It’s pretty much like life anywhere else with a three-year-old. It’s not so much the place as the circumstances that determine what your life is like. We live in an apartment in San Francisco — it’s an alright place to live, [but] we don’t get out much because we have a three-year-old. I get out on tour from time to time; I’m doing a little bit less touring than previously because I want to be home. But only a little bit less; this has been a pretty busy summer and spring. So, you know, life goes on. It’s not very different than what my life was like when I was living at my house near Kingston, Ontario, or when I was living in Toronto.