Media Archives

1994-2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 / 2007 / 2008 / 2009 / 2010 / 2011 / 2012 / 2013 / 2014 / 2015 / 2016 / 2017 / 2018 / 2019 / 2020 / 2021 / 2022 / 2023

July 3, 2024

Toronto Star

As he gets inducted into the Mariposa Hall of Fame, Bruce Cockburn looks back on the highs and lows of summer festivals

The 79-year-old musician will play the Lightfoot Stage at the Mariposa Folk Festival in Orillia on July 7.

By Nick Krewen - Special to the Star

The second time he played Orillia’s Mariposa Folk Festival, in 1969, Bruce Cockburn wasn’t supposed to headline.

That honour belonged to Neil Young, fresh from his split with Buffalo Springfield, until a last-minute health issue forced the Ottawa-born folksinger and songwriter — who, until that point, had played in such bands the Children, the Esquires, the Flying Circus and 3’s a Crowd — into the spotlight.

“I was terrified,” recalled the 79-year-old Cockburn from his home in San Francisco. “But I got up, did my little half-hour set and people liked it. It was really the first time I played as myself in front of a big audience.

“It was pretty intimidating, but I got away with it. And it set me up in a pretty great way in terms of the Toronto folk scene.”

Cockburn, who will be inducted into the Mariposa Hall of Fame at 7 p.m. on Sunday, following his ninth performance at the Tudhope Park event, looked back fondly at the festival’s earlier years.

“In the beginning, it was the only one (festival),” he remembered. “Later on in the ‘70s, the western festivals started up — Winnipeg and Edmonton and Vancouver — and they were good festivals, too.

“The scene was great. Back in those days ... I’d play whatever I was there to do, and the rest of the time I’d go around and hear this amazing music that you might never encounter otherwise.

“There was also a nice social part of it, too. You’d get to see the people that over time you’d get acquainted with, and you’d only see them at festivals.”

Cockburn — whose upcoming performance on the Lightfoot Stage caps a diverse July 5-7 weekend lineup that includes Canadians William Prince, Maestro Fresh Wes, Bahamas, Donovan Woods and non-Canadians Noah Cyrus, Band of Horses and Old Crow Medicine Show — appeared every year at Mariposa from 1968 to 1972.

He returned in 1974 — and then played sporadically, finding himself in demand elsewhere due to his growing worldwide popularity, fuelled by a successful recording career and international hits such as “Wondering Where the Lions Are” and “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.”

“The way we toured changed completely,” he said. “Back in that era, we spent half the year driving around Canada in our pickup truck with a camper on the back. That’s what a tour was: you’d play Winnipeg and a month later, you could play Saskatoon, and a month later, you’d play Edmonton. In the meantime, you’d have all this time to hang out and explore. I fit into that kind of scenario very well.

“But now, with Mariposa, for instance, we’ll arrive 3 a.m. the night before and leave after the show or that night — and that’s the most I can get out of it.

“I can’t walk around and enjoy the festival so much because people want to talk to me ... which I like. It just doesn’t give me the same opportunity to stay for some music that you’ve never heard before or artists that are new to you.”

Cockburn is also known for his activism, and his songs have covered everything from human atrocities in war-torn countries to environmental concerns to romantic love.

Over the course of a career that has lasted more than a half-century, the former Berklee College of Music student has expanded his horizons from folk to other genres, expressing himself and his immaculate guitar work on 40 studio, live and compilation albums that earned Cockburn entry into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, the Order of Canada and a dozen Juno Awards.

His latest album, “O Sun O Moon,” came out in 2023, which raises the question: does Cockburn have plans for another?

“At the moment, no. I haven’t written anything,” he said. “What we’re thinking about doing is an album of other people’s songs. I’ve wanted to do this for decades. Now might be the time to do it, before it’s too late, I suppose.

“I’m not going to be covering other singer-songwriters particularly. I have some connection to what I grew up with — and just songs I like — old stuff, primarily. Some of it’s blues ... some of it is (standards). Some of it’s whatever ragtime is.”

He’d also like to tour with a band again, considering his treks over the past several years have featured just him and his posse of guitars.

“I don’t know if we could pull it off,” he said. “If I was playing big shows like I play in Canada, we could do that. But those big shows are mixed with a whole bunch of U.S. dates where the audiences and the venues are smaller, so it’s hard to make that work economically.

“I like playing solo and I think it works really well because of how intimate it is and how it makes people really feel the songs. But I miss having some extra energy on stage with me, and I think people have seen enough of the solo thing now. It’d be nice to add some other players, but I have no idea if and when that will actually happen.”

What is planned is a Moroccan vacation with his wife and daughter immediately following the Mariposa ceremony; a stay in Ontario in August while his daughter attends summer camp; and then a return to San Francisco, where he’ll rehearse for November solo dates.

As for the “R” word: retirement?

“Well, it’s in my vocabulary but not in my intentions,” Cockburn said with a chuckle.

“Who knows? At some point, the hands will give out or some other body part will give out or the brain, and I won’t be able to continue. But until that point, I don’t see any reason to stop.”

As for the Mariposa induction, Cockburn — who recently received an honorary doctorate of music from Sir Wilfrid Laurier University, his 10th such degree from various institutions — said he’s thrilled to join such peers as Ian & Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, Murray McLauchlan and the Travellers.

“It definitely feels like an honour and a welcome kind of recognition,” said Cockburn. “But it isn’t a life-and-death thing. I’m very happy to be included in the Hall of Fame, and Mariposa over the years has meant quite a bit to me, especially at the beginning. So, it’s pretty meaningful that way.”

June 3, 2024

SooToday

Sault author's Bruce Cockburn book wins indie publishers award

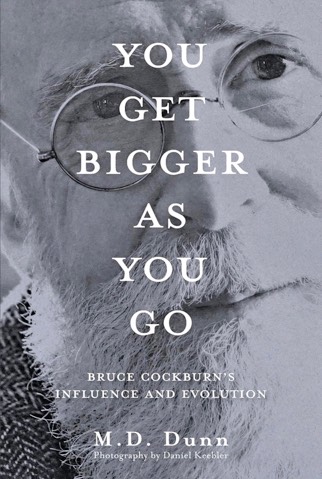

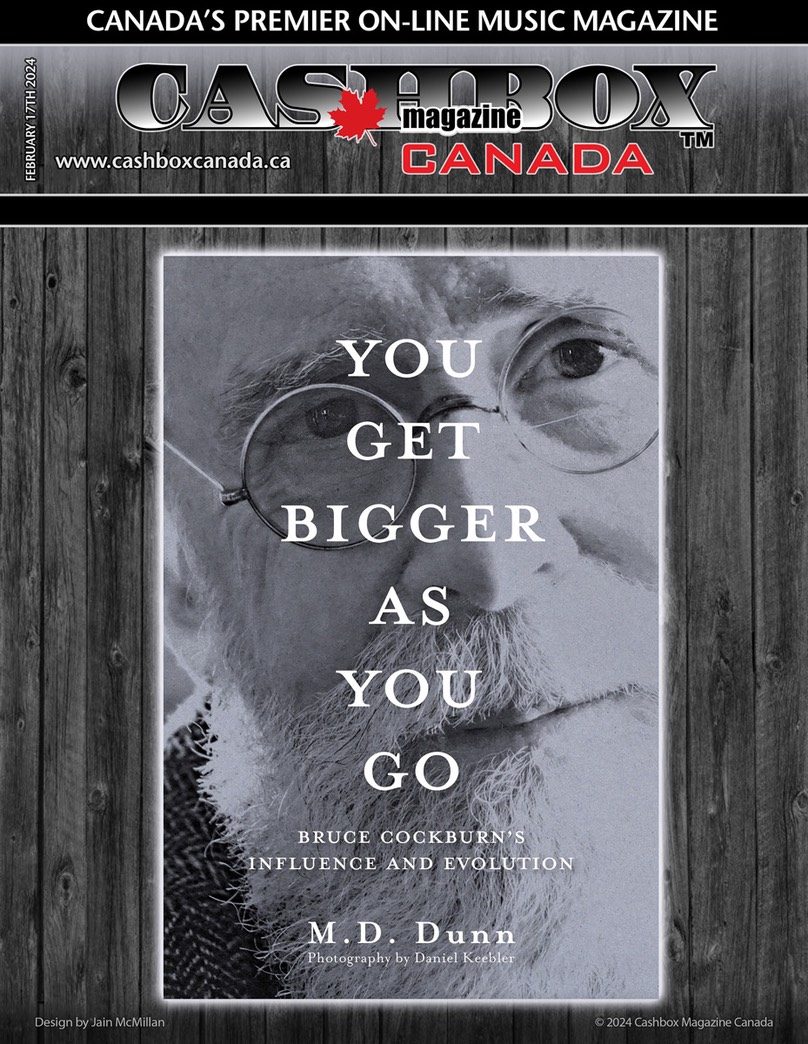

A book by a Sault-based musician and author has won an "IPPY" award.

Fermata Press says that its first title, You Get Bigger as You Go: Bruce Cockburn’s Influence and Evolution by M.D. (Mark) Dunn, with photography by Daniel Keebler, has been awarded the 2024 bronze medal for Best Book in Performing Arts from the Independent Publisher Book Awards (The IPPYs).

Established in 1996, The IPPYs are the longest-running award for independent publishers with thousands of titles from 2,400 English-language publishers worldwide considered each year, the publisher said in a release.

The book has been an Amazon bestseller in multiple categories since its publication, Fermata Press said.

It has been featured in The Globe and Mail, Literary Review of Canada, Cashbox Canada, on CTV News, CBC Radio, many podcasts and radio programs, as well as on SooToday.

The book is described as "a beginner’s guide to and celebration of the music and cultural presence" of the Canadian songwriter, guitarist, and activist.

"It is also an eclectic and humorous look at the ways music can transform the individual and society," Fermata Press said.

Written over seven years, the book features original interviews with Cockburn, his manager Bernie Finkelstein, and musicians and producers who have worked with Cockburn over his five-decade career.

"Fermata Press and M.D. Dunn are grateful to the selection committee and to the many readers worldwide who have embraced the book," the publisher said. "Special thanks to editor Allister Thompson and designer Laura Boyle for their invaluable contributions."

For more information about the IPPY Awards, visit https://ippyawards.com/178/2024-medalists.

To learn more about Fermata Press and You Get Bigger as You Go check out www.fermatapress.com.

Visit M.D. Dunn's website for music and other writings at www.mddunn.com

June 1, 2024

Concert review: Ottawa's musical legend, Bruce Cockburn, entrances hometown audience

Fortified by a repertoire that spans almost six decades and a number of stylistic shifts, he delivered two generous sets.

by Lynn Saxberg

On Friday, four days after his 79th birthday, Bruce Cockburn gave a wonderfully vibrant and expansive solo performance in front of a hometown audience packed to the rafters of the National Arts Centre’s Southam Hall.

It was a top-notch concert that showed the songwriting legend in peak form musically, his distinctive voice strong and his brilliant guitar work polished to the highest calibre.

But our first glimpse of the Ottawa-born Canadian Music Hall of Famer prompted a ripple of concern. Hunched and bearded, a cane in each hand, he looked every bit his age as he made his way to an elevated stool flanked by guitars on one side and a wind chime on the other. He was met with a warm round of applause from a room filled with friends, fans and family members.

“Happy birthday,” yelled one enthusiastic voice in the crowd, a belated wish that Cockburn observed was starting to get a little old, before he caught himself.

“Other things are getting old, too,” he deadpanned, stating the obvious with a self-deprecating dig that lightened the mood, putting everyone at ease with his laidback sense of humour.

Then he tripped over the start of the first song, chuckled at himself again and recovered like a pro, settling into the haunting groove of The Blues Got The World, a tune he said he wrote while studying for the clergy.

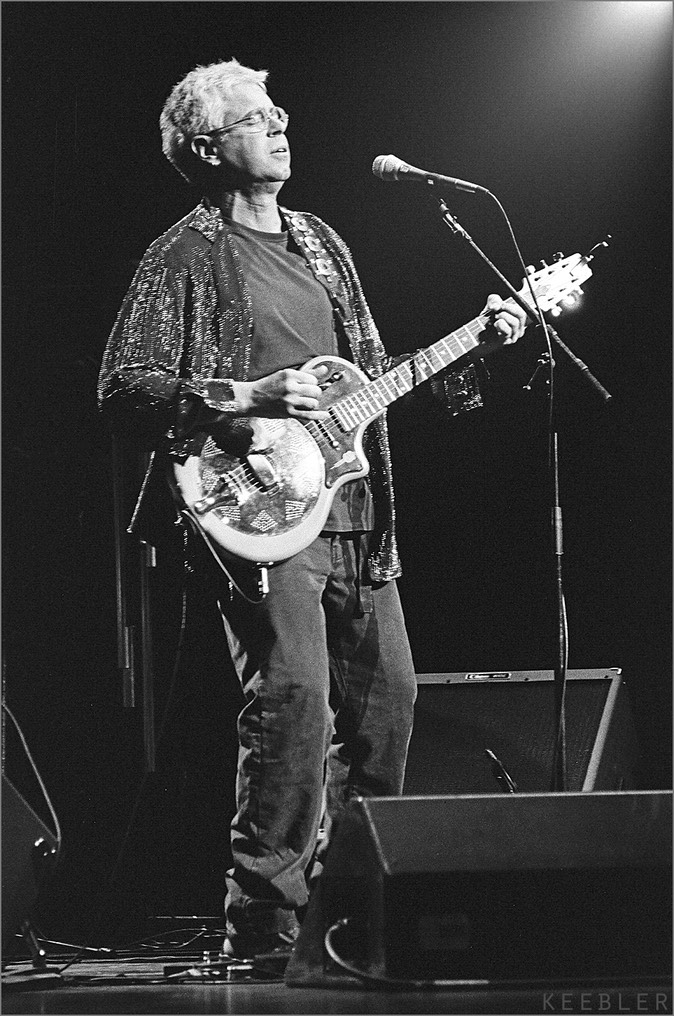

With his chrome dobro catching the stage lights, next came the mournful Blind Willie Johnson lament, Soul of a Man, followed by the rich imagery of The Whole Night Sky. The sound was pristine, the audience entranced and the mood almost spiritual.

Cockburn, who now lives in San Francisco with his wife and preteen daughter, switched instruments a few times, choosing between several acoustic guitars, including his green Manzer, as well as a little green charango, which looked like a 12-string ukulele, and even a mountain dulcimer, played on his lap.

Fortified by a repertoire that spans almost six decades and a number of stylistic shifts, from folk to jazz to rock, Cockburn delivered two generous sets, taking his time and showing no sign of fatigue. He focused on his most evocative material, including gems like Last Night of the World, Stolen Land, 3 Al Purdys, Lovers in a Dangerous Time and his 1980 breakthrough hit, Wondering Where the Lions Are.

Another highlight was a sweeping version of his landmark 1989 protest song, If A Tree Falls, that found the long-time activist railing against deforestation in lyrics so relevant that they could have been written last week.

Also nestled in the setlist were some of the powerful, understated songs from Cockburn’s excellent 2023 album, O Sun O Moon, including King of the Bolero, Push Comes to Shove and Orders, contributing to the zen-like vibe of the evening.

Sixty years after graduating from Ottawa’s Nepean High School, with a yearbook entry proclaiming he intended to be a musician, Cockburn also took the time to recognize a fellow Nepean student, Peter B. Hodgson, who’s still around and better known by his stage name.

“One of the great things about high school for me was one of my classmates, who was a great inspiration to me as a guitar player and kind of introduced me to the whole world of folk music,” Cockburn said. “I’m talking about Sneezy Waters.”

The shout-out earned another round of applause, and Cockburn went on to wrap up the encore with a pair of nuggets from the latest album, the world-weary Into The Now and the bittersweet When the Spirit Walks in the Room, dropping his voice to its gravelly depths to emphasize the message that we’re all but a “thread upon the loom.”

All in all, it was a fantastic performance from a musical legend who has clearly worked hard to remain at the pinnacle of his abilities despite the physical challenges that come with aging. In other words, he’s still got it.

May 23, 2024

Everything Zoomer

“I Don’t Want to Stop”: Bruce Cockburn, 78, on Touring, Family and Why Older People Should Go to Concerts

by Karen Bliss

Bruce Cockburn has been touring regularly since releasing his 27th studio album, O Sun O Moon, last year, and the legendary 78-year-old Canadian singer, songwriter and guitarist wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I don’t want to stop. Even if I could, I wouldn’t want to,” he notes during a recent phone interview.

The outspoken political and environmental activist, known for such hits as Wondering Where the Lions Are, Lovers in a Dangerous Time and If a Tree Falls kicks off a run of 10 Canadian dates on May 24 in Lindsay, Ont. In November, he’ll head out on another U.S. leg.

The Ottawa native, who lives in San Francisco with his wife and 12-year-old daughter – he has a grown daughter from his first marriage – has been releasing albums since his 1970 self-titled debut. Along the way, he he has amassed 22 gold and platinum records, including a 1993 holiday album, Christmas, that went 6x platinum, not to mention a myriad of other accolades and recognition.

With that sort of resumé, he’s been inducted into Canada’s top halls: the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, Canada’s Walk of Fame and the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame. He was invested a Member of the Order of Canada in 1983 and promoted to Officer of the Order of Canada in 2003, and presented with Governor General’s Performing Arts Award in 1998. He also has 13 Juno Awards, the Allan Slaight Humanitarian Spirit Award, and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. He was even featured on a postage stamp.

This summer, he will receive yet another academic award, this time an Honorary Doctorate of Music Degree on June 14 from Wilfred Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont. and, on July 7, will be inducted into the Mariposa Hall of Fame during the fabled folk music festival in Orillia.

But before that, Bruce Cockburn spoke with Zoomer about life on the road in your 70s, why older people shouldn’t dismiss the live concert experience, what Mick Jagger does on tour that he doesn’t, and why he won’t retire.

KAREN BLISS: Mick Jagger posts photos of himself on his Instagram during tours, where he visits local sites and even the occasional bar. Do you find time to do that when touring?

BRUCE COCKBURN: I was more like that in the 70s, when the pace of the work was much lower. You could do a cross-Canada tour, and it would be 12 shows, especially the early half of the 70s, we just drove ourselves around. So you could play Winnipeg and then take a month to get to Saskatoon. Winnipeg would pay for your life during that month, so back then, there was all kinds of time for exploring and having adventures. But at this point, to make it economically feasible, we have to work pretty steadily. That, combined with age [laughs]. I don’t have the energy to go wandering around now. I have to save it all for the show. But by doing that, I’m able to do the shows the way I think I should.

KB: In other careers, people often work in order to retire. In the music business, there are so many artists still touring in their 60s, 70s and 80s. It’s a fascinating art form and job because creatively, it’s solitary, but you need to share it to connect.

BC: Yeah, that’s absolutely true. But, it’s also a factor that the people who are working toward retirement are probably expecting a pension. We ain’t [laughs]. We’re not getting that. Musicians, athletes, anybody remotely connected to entertainment, unless you become rich enough that it doesn’t matter – which some people do, of course – there’s an incentive to keep working because you keep getting paid.

But you’re right about what you said, though. Nonetheless, I don’t want to stop. Even if I could, I wouldn’t want to. I guess, technically I could, but my family and I would have to make some different plans. But I just see myself going until I drop, incapacitated, which could happen easily. I mean, at this this point in anyone’s life, you don’t know what body part’s going to give out [laughs]. Then I’m going to be retiring.

KB: Are you meeting fans on this round that tell you stories about what your music has meant to them?

BC: I haven’t been doing that so much lately, but before COVID I was going out to the merch table and signing stuff. I had a lot of conversations. I did that for years. But COVID put an end to that. When we started having shows again after COVID, after the shutdown, it seemed too risky to be shaking all these hands. And then, I just never got back into it. I do slightly miss that – not enough to start doing it again at the moment – but it was nice to hear some of the stories … Sometimes people had really touching stories of how the music had affected them or sometimes people were just so enthusiastic that it made you feel happy to meet them.

KB: I’m sure there are a lot of Zoomer readers who don’t go to concerts anymore. What would you say to them in terms of that connection you get from experiencing live music?

BC: If you like listening to music in the comfort of your living room, that’s fine. And if you have a good sound system, it can be a rich musical experience. But it’s not the same as being in a room full of people, sharing the time and space through the music. There’s a sense of community that develops. It includes me and the audience. It’s one of the things that makes me want to keep doing it, that feeling of everybody coming together, in effect, celebrating our existence. And I think people should give themselves a chance to experience that, if they can. I mean, some of us old folks don’t get out so much and it’s just hard work to do it. So there’s a reason why we don’t go out. But if it sounds appealing at all, it’s worth the effort.

KB: You have a young daughter. Does she appreciate what you do?

BC: Yeah, she does. She likes coming to my shows. She’s 12. She’s been coming to my concerts since she was two months old. So she’s very familiar with what a show is like backstage, front stage – the whole scene.

KB: When she does come on the road with you, I guess that’s an opportunity for you to do things in cities that you wouldn’t normally do, like find a great ice cream shop or check out a waterpark?

BC: No, we have a friend named Celia Shacklett, who is a children’s entertainer that lives in St. Louis. Celia and I have been friends since the late ’80s. She’s a free spirit and a freelancer. When we first started to bring [my daughter] on the road when was a baby, we got Celia to come along and help with her. So Iona grew up with our friend Celia. And when Iona comes on the road, one of the attractions is we try to get Celia to come on the road too and they get to hang out. I mean, Iona doesn’t need that kind of looking after now, but they’re such close friends so they go to libraries, they go to museums, they go to the toy stores, whatever’s around. But I don’t get to do that because my days are filled.

KB: You’ve got the soundcheck, press, sleep.

BC: Exactly.

KB: In two years, you will be turning 80. Do you have a plan of how you want to celebrate?

BC: Yeah, my wife’s gonna turn 50 and I’m gonna turn 80 within a couple months of each other. So I don’t know, we’re gonna cook up something.

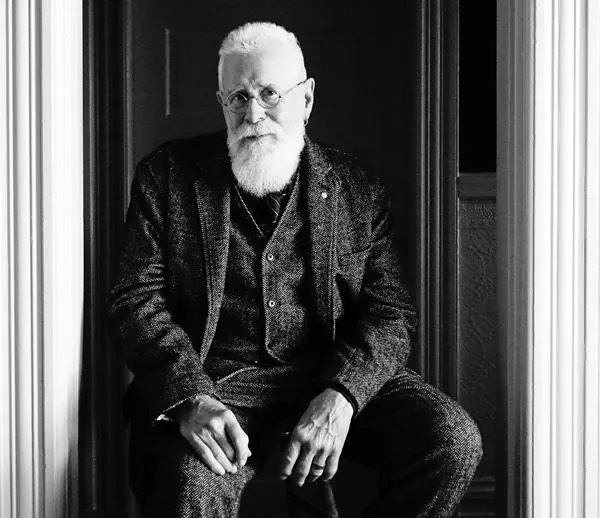

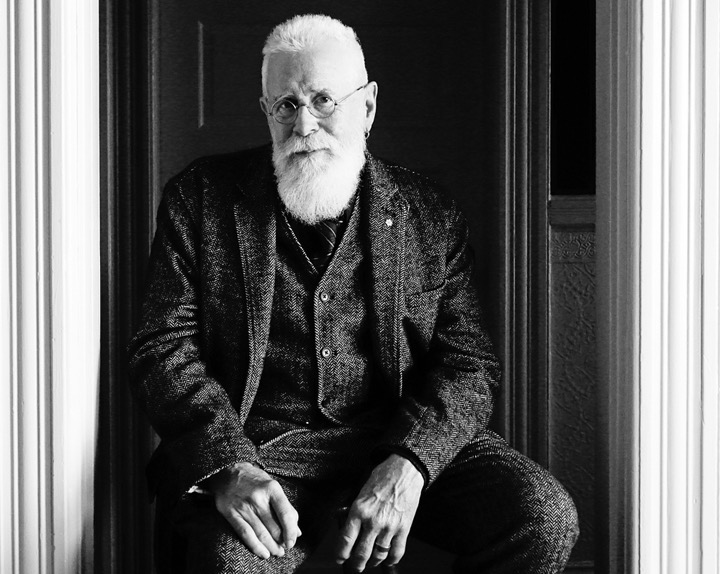

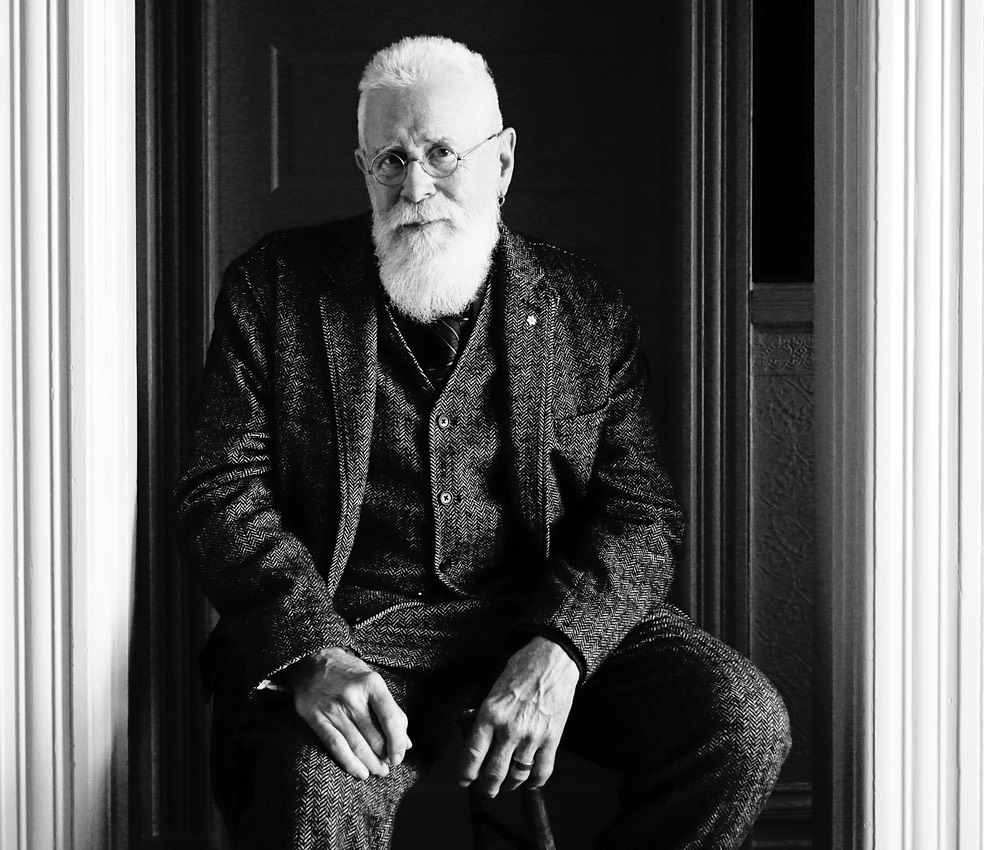

Photos in order: Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press - Sean Kilpatrick/The Candian Press - Graham Bezant/Toronto Star via Getty Images - Studio photo by Daniel Keebler

May 17, 2024

Canadian Songwriters Hall Of Fame

Bruce Cockburn: A Career in Review and the Future Sound of Music

by Karen Bliss

Singer, songwriter, and guitarist Bruce Cockburn—inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2017—has written hundreds of songs spanning 27 studio albums over a 50-plus year career, amassing 22 gold and platinum records, including 6x platinum for his 1993 Christmas album. His self-titled debut album came out in 1970, on the label his long-time manager Bernie Finkelstein’s created, True North Records.

An outspoken political activist and humanitarian with a firm stance against warmongering and environmental decay, the Ottawa native is known for such hits as “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” “Lovers in a Dangerous Time,” and “If a Tree Falls.” Still writing songs that are relevant and true, at 78-years-old he is still a workhorse. Last year, he dropped the stellar album, O Sun O Moon—produced by Colin Linden—and has since been touring extensively in Canada, the U.S. and overseas.

In between show dates, he will pick up another Honorary Doctorate of Music Degree on June 14 from Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, and on July 7 will be inducted into Mariposa Hall of Fame during the folk music festival in Orillia.

He has already been inducted into Canada’s top halls: the aforementioned CSHF, the Canadian Music Hall of Fame (aired during the JUNO Awards) and Canada’s Walk of Fame. He was invested as a Member of the Order of Canada in 1983 and promoted to Officer of the Order of Canada in 2003. Later in 1998, he was presented with the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award. Bruce has also earned 13 JUNO Awards, the Allan Slaight Humanitarian Spirit Award, and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. He was even featured on a postage stamp in 2011.

Cockburn, who lives in San Francisco, talked with the CSHF during his recent U.S. leg. He starts a run of Canadian dates on May 24.

You have toured everywhere. When you put together a tour these days, do you try to include places you’ve never been or space them out so you can visit a museum or a place you enjoy?

[laughs]. It’s not very romantic. Basically, Bernie calls the booking. Where can we do it that’s practical and that we haven’t been to most recently? That’s the main concern when you’re looking at a geographical area. Sometimes, it comes out of a promoter making an offer somewhere, like if we got a good offer to play a festival in England, then we would try to find other shows in England to put around it. But, for touring around North America, right now we’re booking for next March and putting on a tour on the West Coast.

What do you remember most fondly about the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame induction, the same year as Neil Young, at Massey Hall?

I remember most of it. I think William Prince and Elisapie doing “Stolen Land” was a wonderful thing. Buffy Sainte-Marie’s introduction of me was fantastic. I was so touched by that. She just said great stuff. It was smart and right on the money, as far as I was concerned. So, that’s what I remember most.

And I also remember being slightly shocked by the fact that Neil came with Daryl Hannah, his current partner. I had met Daryl back in the ’80s when she and Jackson Browne were together. I went to an event at their house in L.A. Daryl Hannah, all these years later looked exactly the same as she did when I met her the first time, which was like, “How did you do that?” You know, we know how it gets done by some people [laughs].

She has very good genes, that’s for sure.

Having seen her in the movies, like Kill Bill, where she actually does look older in those movies. But there at Massey Hall, she looked exactly the same as when she answered the door when I went to their house. And, it was kind of like, “What are you, a vampire?” But Neil, of course, I don’t know him well, but we’ve been acquainted for a long, long time and he and I both look our ages. But Daryl didn’t. Those are memorable moments.

You said something at the induction about your long-time manager Bernie: “In a world increasingly defined by its fakery, we together have pulled off the greatest trick ever—we spread truth.” Do you remember writing that in your speech?

Yeah, vaguely, yeah.

Do you remember what you meant by that? The “we spread truth” part?

Bernie’s a businessman; I’m an artist and the relationship we have is symbiotic. Bernie still manages me because he loves the music. And he’s proud of it. I do it because I love the music. I like getting paid, of course. But I don’t do it for the money. I’d be doing it if I weren’t getting paid.

Okay, it sounds a little grandiose, put it this way: I want my songs to be truthful. That doesn’t mean they can’t be fictional. It’s the same way you can put truth in a novel.

You can put truth in any kind of song, but they need to have an emotional truth. And, when facts are cited, like I said, it can be distorted in a fictionalized way, but, in general, I’m trying to tell some kind of truth. I’m trying to tell my spiritual truth, trying to leave a record of my journey through life that may be of use to someone, or may not, but if I don’t put it out there, it won’t be of use to anybody.

So that’s why I do this. And, to me, it’s all about truth in the biggest sense with a capital “T.” I might exaggerate something or diminish something else, for the benefit of making a song entertaining and interesting, but it has to come from a real place inside me. And that’s what I have to share. Without that, there’d be no point in doing it. Without that, I would be doing it for the money. And so that’s why I called it “truth.”

Working with Bernie this long, that is rare in business. Is there something you can point to that has been the key to how you have been able to work together all these years, through all life’s ups and downs?

Well, I think the point one is it’s always worked. So, why mess was a good thing? But, also, like any relationship, it’s required patience and tolerance and forbearance, on both our parts, and the ability to step back the frustrations that come with dealing with anybody over time. So far, we’ve been able to do that. We’ll probably be able to continue.

Would you consider selling your catalogue the way a lot of your peers have been doing? Gives you cash in the bank and songs are complicated for your estate, your family.

I did do that. When I became a legal resident of the U.S., for tax reasons, it didn’t make sense. The advice I got from my accountant was don’t own a corporation in Canada and live in the United States. So I sold it. That’s going back now at least 12 years.

You were ahead of what’s turned into a trend with legacy songwriters. Neil, Dylan, Springsteen, so many.

Those guys are doing it because they get so much money. And yes, it simplifies their estate dealings, I guess. But, for me, it was a practical decision that I would have preferred not to do, actually, because I like the idea of having control over what happens to the songs. But, at the same time, and it’s not a total picture, because I have a publishing company that owns the songs that I’ve written since a deal was made.

So, there’ll still be those considerations when I croak, family will have to deal with, but you can’t avoid it anyway unless your economic life is so simple. But, for most of us, it isn’t because of the tax department [laughs]. It’s always complicated. There’s always stuff like that to deal with that you have to try to head off. I mean, we think about that stuff and have tried to make plans that won’t be too difficult to deal with.

As an activist and largely a socio-political songwriter, we have seen young people protesting for tighter gun control, women’s rights, and recently setting up pro-Palestinian encampments at universities, and yet popular music, the songs topping the charts, doesn’t reflect that. Do you think young people’s interest in substantive issues might start seeping into music?

I don’t have much of a sense of what college-age people are listening to. But we’ve seen all this before. In the ’60s, when the Vietnam War was on, especially in the States—there were protests in Canada, too, not necessarily against the war, it was just a thing that people did in fashion, in a way, to have these kinds of events. I’m not trying to diminish the seriousness of it by calling it a fashion, but these things kind of seem to go in waves or phases. And back then, people were killed at demonstrations because they called out the troops, and the troops did what troops do. This is that pendulum swinging back that way again, with different kinds of provocation and different circumstances and slightly different cause, although not radically different, but still the result of U.S. involvement in other people’s affairs.

It will be interesting to see if that starts getting reflected in music.

I think it will. I mean, it’s always been there in rap music. Rap music is hugely popular. Not all rappers do it, but lots of them do take on issues in their music in their material.

So, even if it’s passing references, along with the boasting and whatever else, there’s frequently commentary on whatever’s going on around them. That’s basically what we’re talking about with respect to the demonstrations. So, I’ve got a feeling that it will show up, that we’ll probably see more of it before it’s over.

At this point, it’s hard to know how people respond. I’m not in touch with that. If I were to be a songwriter now, starting out, I’d probably be sitting in my bedroom, looking at my computer and figuring out what to do with that and writing songs.

May 9, 2024

Mariposa Folk Festival

Orillia, Ontario

Press Release

Bruce Cockburn To Be Inducted Into Mariposa Hall of Fame

RUMOURS OF GLORY? “Mariposa has been at various points a really important part of me being able to get my songs out to people.”

The Mariposa Folk Foundation will enshrine Bruce Cockburn in its Hall of Fame at this year’s festival, July 5 – 7, at Tudhope Park in Orillia.

“Bruce Cockburn is a courageous and inspiring Canadian artist who first played the festival in 1968 and has graced our stage 8 times over the years,” said Festival president Pam Carter. “We’re honoured to induct him to the Mariposa Hall of Fame this July during his 9th appearance,” added Carter.

“It’s of course an honour,” said Cockburn in reaction to the news. “Mariposa has been at various points a really important part of me being able to get my songs out to people.”

He recalls his first unplanned mainstage appearance at Mariposa: “I was supposed to do an afternoon set – which I did. And Neil Young was on the bill and Neil had to cancel because he had an ear issue or some problem and – all of a sudden – I was on the main stage so I got up and played my songs and people liked it and it went on from there.”

Cockburn and the Mariposa vibe seem to have always dovetailed. While his songs of protest, love, and spiritual quest have moved many Mariposa audiences over the years, in typical Bruce Cockburn fashion, he remains humble in the face of his Hall of Fame induction.

“I actually look forward to being at the festival more than I look forward to getting this. At the same time, it is an honour and I’m very pleased about it,” said Cockburn who, like many patrons, has appreciated opportunities to immerse himself and discover new artists while at the festival: “The famous people were less interesting to me than the people I had never heard of,” he said regarding his multiple appearances at Mariposa.

A special live and pre-recorded tribute to Cockburn will be held on the evening of Sunday, July 7 at Mariposa’s Gordon Lightfoot Mainstage to commemorate the Hall of Fame induction. “You don’t want to miss the special tribute we have planned for Bruce,” said Carter. “It will be an evening to remember.”

The three-day Mariposa Folk Festival (July 5-7 2024, at Tudhope Park, Orillia, ON) features more than ten stages of top folk-roots music, along with presentations of story, dance, and craft. All ticket categories are on sale. Kids 12 & under are admitted free. The festival has special pricing for youth and young adults. Onsite camping is sold out.

Photo credit: Bruce Cockburn performing at 1972 Mariposa Folk Festival. Photo by Edwin Gailits

May 2, 2024

The Arts STL

Waiting for That Gift: A conversation on inspiration with singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn

by Courtney Dowdall

Bruce Cockburn is a Canadian guitar player, songwriter, and activist who has traveled the world as a “musical correspondent” to document tragedies and triumphs of the human spirit. With a list of accolades and awards about a mile long, he is renowned and respected for his “cinematic” style of songwriting. He has released more than 35 albums over the course of his career spanning 50+ years.

The last time Bruce Cockburn came to St. Louis in October 2018, he sold out the joint. In the intervening years, he’s added two more original albums to his catalog, including his most recent work, O Sun O Moon, released in 2023, in which he continues sharing observations of the human experience: relationships, spirituality, politics, and wonder. He returns to Delmar Hall on May 7.

We had the honor of speaking with Bruce Cockburn from his Canadian home as he returned from the European leg of his 2024 international tour.

The Arts STL: Well, I’m so glad to have this opportunity. I was introduced to your music a very long time ago by my then-boyfriend, who’s now my husband. We were like 13 at the time, and he made me a mixtape that included a lot of music he got from his father. Songs like “Hoop Dancer” and “Rose Above the Sky” and “Tokyo” were some of the first songs of yours that I got introduced to, by my husband’s little 13-year-old poetic soul, which just melted my heart and has been with me ever since. So to have this opportunity was something I absolutely could not pass up. Thank you so much for making the time! Thanks for continuing to make all this amazing music over the years! And thanks for coming to St. Louis next month.

Bruce Cockburn: Yeah, I’m looking forward to it. And you guys were ahead of the curve in the US. With those particular albums and songs and whatnot. Things were just starting to get rolling in the US at that point.

Can I ask, are those songs that I could ever anticipate hearing on tour?

BC: Actually, “The Rose Above the Sky” I have actually done a little bit lately. Not in every show. It’s one that, for me, I always have the dilemma, when I’m planning a show, knowing that there’s only so many long, slow songs you can put in. You know, you gotta have some energy in the show, too. So, that one kind of just got ignored for a long time, and I didn’t think about it too much. Then, when people started asking for it, and [it] came up in conversation so many times recently, that I started learning to do it again.

How does it feel to revisit those songs you haven’t played or had those words coming out of your mouth in so many years?

BC: It kind of varies. On the one hand, it’s interesting to revisit the songs like, ‘Does it still mean the same thing? What did I mean by that?’ A song like that—all the songs, really, take me back to where I was when I wrote them. Kind of like looking at a photo album of old photographs. So, I have mixed feelings about it generally. Because it’s a song that has pain in it. That’s there. It’s also fun to kind of go back and figure out how to do the damn thing. There’s a lot of guitar parts I don’t think I’d be able to figure out, having forgotten what they were. I guess, given enough time, I might be able to, but some of them were fairly complicated. That one wasn’t too bad, but some of them are quite challenging.

Would you ever consider having a pinch guitar player? We recently saw Elvis Costello and there were a couple of times where he said, “You know what, I want to play this song, we’ve got the full band, so I’m gonna let somebody else take over the guitar work on this, because it’s just not as familiar to me anymore.”

BC: No, I’ve never done that. I have occasionally reworked guitar parts. There were songs, some of the stuff from the mid-‘80s, where the bands were big and the guitar parts were shrunken, to accommodate all the different instruments—to figure out solo versions of those songs. A song like “See How I Miss You” or “World of Wonders,” those I had to invent new guitar parts for, because the original ones were designed to be part of a big band.

In other cases more recently, because I’ve got arthritic hands, I’ve had to rework the guitar parts in some quite familiar songs that I have played a lot, just because it’s become too difficult to play them properly. I mean, I can kind of hack my way through “Pacing the Cage,” for instance. I’ve just now relearned that, or reworked it, rather. Because I hadn’t forgotten the song, but the original way of playing it was not available to me anymore. There’s a few songs like that, that I’ve had to rework. And that’s also fun, actually, because it’s kind of a challenging exercise: how do I get the same feel and keep the same relationship between the guitar and the melody, and do it a different way?

What are the important pieces to keep? What is essential?

BC: Exactly. The guitar parts are essentially, except for some of those ones in the ‘80s, they’re basically compositions that are designed to go with those lyrics and that melody. It’s not quite like writing a whole song to come up with a different guitar part, but it’s a little bit in that direction. Trying to keep the same sense of what the composition is, and play it a different way, can be a little tricky. But that said, it’s been working with a few songs that I’ve had to do that with. Most of the stuff is not a problem because, you know, they do what I want them to do. But with some it has presented that issue.

What has been your response or your reaction to cover songs? Or other versions? Does it feel like they capture the same pieces that are important to you? Or maybe pick up on a different piece that wasn’t your emphasis but was more critical in their interpretation?

BC: Yeah, once in a while, it seems like somebody actually got the song. Most of the time, it doesn’t really seem like that to me. I mean, I respect the fact that everybody is going to do their own take on the songs. That’s what they should do. But sometimes it feels to me like they didn’t really understand what it was that they were doing, what the song was.

Other times, it works great. When Jimmy Buffett died, my wife started playing a whole bunch of Jimmy Buffett stuff, including five songs of mine that he did. And there’s a duet with Nancy Griffith of a song called “Someone I Used to Love,” another slow song, that I do too many of in a show. They did a beautiful version of it that really captures exactly what it should be. And yet, it’s clearly them doing it. Judy Collins did “Pacing the Cage,” and that worked great. Other people… sometimes… you know, it might be an age thing, maybe I’m not sure. I just thought of this, because the two examples I gave are both mature people looking at songs from a perspective of having had a life. And some of the younger artists that record the songs, I’m not sure that they actually know what they’re about. But that’s a sweeping generalization. And it’s probably unfair to a whole lot of people. There are many, many recordings of my songs that I haven’t heard, too. So, nobody should think I’m picking on them in particular.

That must be exciting to hear so many different versions and perspectives reflected back to you.

BC: There was a Toronto guitar player, Michael Occhipinti, [who] recorded a whole album of my stuff, and it was completely deconstructed and made into jazz, and it’s really good. And it was really interesting to hear that take. There’s no lyrics, it’s just the music, but the version of “Where the Lions Are” is pretty amazing. And who would have guessed that you could take it in that direction? Certainly not me. So, there’s that side of it, too. It’s not a question of how much they mess with the song. Unless they don’t mess with it in a respectful way, or, rather, unless they mess with it in a way that isn’t respectful, or it just doesn’t sound like it gets it.

I’m gonna have to look for that. That sounds amazing. Do you have any role models or any folks that you’ve looked to for the way they’ve advanced their career or approached their music over time? Like, “That’s the way to do it. They did it right. That’s how I want to do it.”

BC: No, I don’t think of it that way. There’s been many people who’ve influenced what I do over the years, dozens at least, but some major ones back when I was getting started and just trying to understand what music was all about… There were guitar players: Wes Montgomery and Gabor Szabó. There were old blues guys: Mississippi John Hurt, Mance Lipscomb, Brownie McGhee. There was Bob Dylan and other songwriters in the ‘60s. That was an era when a lot of us got beyond the limitations of pop music in terms of our understanding of what you can do with a song. Dylan in particular, but others too, who were exemplary. Gordon Lightfoot would be another one. People who were writing beautiful songs that were more than ‘baby I want to …’ There’s nothing wrong with that kind of song, but it’s –

It’s a different kind of song.

BC: I mean, I cut my teeth on Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, And that’s pretty much all they play, pretty much all they were saying, was, you know, getting or trying to get laid or wishing they were getting laid. That was fine. It was exciting as a 12- and 13-year-old. But the discovery that you can write songs that actually said stuff was eye opening. Some of my friends, when I connected to the folk world, in my latter teens, I hooked up with people who have been aware of this kind of stuff all along, they’ve listened to Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and all these people I had never heard. So for me, hearing and discovering those kinds of songs, but then right away, along came Bob Dylan—I didn’t think of myself as a songwriter, I just related to it really well. At the time, I was just a guitar player. And that’s all I aspired to be. I went to music school to learn jazz composition, to write music for big bands. That’s what I thought I was going to be doing. And then I got seduced by songwriting and went that way.

I read this quote of yours somewhere: “My job is to try and trap the spirit of things in the scratches of pen on paper.” Is that your transition from just the instrumental piece to capturing the words as well as the music?

BC: Very much so. I didn’t understand what I was doing, at first. I thought, “I’m listening to these people that are writing these great songs, maybe I can do it, too.” And the first song I remember writing was very derivative of early Lightfoot. Fingerpicking, nature imagery, and I don’t even remember any details of it now, but that’s what it was then. And then I was heavily influenced by blues and listened to a lot of blues. Not so much Chicago stuff, but the old country stuff, and jug band music and all that. Those were the roots.

And rock and roll. I was playing in rock and roll bands as I was doing gigs in the folk scene, solo or with friends. With hindsight, the second half of the ‘60s was all about learning how to write songs. And I wrote a lot of songs that I pray no one will ever hear during that period. But by the end of it, I had a body of stuff that I thought was worthwhile. And I liked it better when I played those songs myself than when I played them with any of the bands I’d been in. So, that that’s what went into my first album and half of the second one

So, speaking of the blues, I just stumbled upon this video of you meeting Ali Farka Touré. What an amazing experience that must have been. I know travel is very important to you and your music. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about travel and why it’s so important for, for that job, to track the spirit of things? Or for just being a human in general?

BC: Well, I’m not sure travel is required. But it’s been part of my life just because I like doing it, and because I’ve been given the opportunity for interesting kinds of travel on many occasions now.

The trip to Mali wasn’t about songwriting; it was about desertification and making a TV documentary about that, and how that particular group of people there were dealing with it. But because I play music, and because I have listened to some music from there, we thought it’d be cool in the process of the film, if they tried to put me together with some Mali musicians. Toumani Diabaté, the duet I do with him is better than the thing with Ali Farka Touré. It came out really, really well. But the Ali Farka Touré thing was just happenstance. We went to Timbuktu, and we were planning to stay overnight. We were on our way to our ultimate destination, further southwest of there, but we thought we’d go through Timbuktu and see it because we’re so close. So we had a hotel there, and the hotels are not like staying at a Holiday Inn. There were a whole bunch of Americans there. Two guys had this radio show called Afro Pop—I don’t know how popular it was, but it was syndicated. I don’t know if it was on NPR, but it was that kind of show, where they just looked at music from all over Africa. And they had organized the tour. So, there was like a dozen Americans, also at this hotel, and Ali Farka Touré was going to play for them that night.

I had met him at a festival in Canada, some years before, which he reminded me of, actually. I knew about him, but I didn’t remember that I’d actually met anybody. “Oh, Bruce!” and he shows up wearing a purple three-piece suit and a purple Fedora, which is like—you don’t dress like that Timbuktu. You could, you can, and of course he does. But everybody else is looking pretty poor and traditional with turbans and robes and whatever, so there he is doing this. And he invited me to sit in with him. That’s what you saw. It was fun. That whole trip was super interesting. But also, if you’re gonna look for the video of that, the film was called, River of Sand, I think you can get to it from my website. It’s got that in it, and the duet with Toumani Diabaté, and an older guy whose name escapes me at the moment, an older guy that played an instrument called an ngoni, a precursor to the banjo. That’s pretty cool, too. So there’s that music and then the film itself is—if you’re interested in the topic, it’s interesting.

Absolutely. So, it was the issue that drove the trip, and this was kind of serendipitous.

BC: That’s been the case with most of the more exotic travels that I’ve taken. It’s never been about going looking for songs. It’s always been about what people are doing in certain kinds of situations. In Nepal, the two trips in Nepal were under the auspices of a Canadian NGO that does development work there. And the two trips in Mozambique—one was about feeding people displaced by the civil war that was going on, and the other was about the landmine issue after the war was over. People can’t go back to farming because there’s landmines all over the place.

I’ve done lots of traveling just for my own amusement, too, but that’s more like being a tourist and less likely to produce the interesting song content than some of these other trips.

Do you feel like those travels influence your sound as well as your ideas and your activism?

BC: I think the Mali trip did. There’s a couple of songs that relate to that on Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu. In some of the songs on that you can hear a little bit of that West African influence in the guitar playing. Maybe, or I imagine it’s there, it is certainly there in the lyrics to the song. Central America didn’t really influence me much musically. They have great music there, and the same with Mozambique. That had less effect on me than the stuff I was seeing apart from music.

No marimba solos after your Guatemala visits?

No, I mean, I like marimba. There’s no video of it, but I did jam with a band of some Guatemalan refugees, in the same setting in which “Rocket Launcher” came from. These refugees had carried the marimba from their village when they fled what they fled from, which was horrendous stuff. Everybody carried a piece of it, and they put it back together when they could settle in this makeshift refugee camp. And because we showed up with guitars, they pulled out the marimba. These guys put on their good shirts.

And, the way they play, two to three people play the same instrument. One guy plays bass parts. One guy plays chords. And the other guy plays the melody. It’s like having a giant piano with three people playing it. It was really interesting. And little kids all danced around. It was very poignant actually, because the situation they were in was horrible. But they were partying when they had a chance.

That says so much, that that was a priority in that horrible journey. That was a priority, to bring that instrument.

BC: I was amazed by that. It says something really good about those people, the degree to which they had their crap together. They were organized. They had absolutely no food, they had no prospects, but they were keeping their organization together and keeping the families together and maintaining their dignity. It was kind of heartbreaking.

I imagine you’ve probably seen a lot of heartbreaking things in the places you’ve been and the issues you’ve dug into and tried to be supportive of, or tried to be part of bringing light to those issues. Do you consider yourself an optimist? An idealist? How do you do that?

BC: [laughs] I don’t think in very optimistic terms, but I can’t shake the feeling that things are alright. I’m not in Ukraine right now. I’ve never been a victim of those things myself. I’ve been up close with some victims, and I certainly heard terrible stories from those people. And of course, you don’t have to look hard to find terrible stories in the news. But I just can’t shake the feeling that something’s going to be alright. But it doesn’t stand up to rational scrutiny because when you look around, it just feels like everything’s going straight down the tubes.

You know there are some bittersweet comments on your new album as well. I’m going to read you another quote I found—“Part of the job of being human is just to try to spread the light, at whatever level you can do it.” You still seem to be effective at spreading that light despite it all.

BC: Well, that’s not my light. It’s the light that I receive. I think the point of being alive is to spread it, so I’m grateful when a song is given to me that does that. In a way, it’s an ongoing theme for me. It didn’t start out as a conscious thing, but it’s what seemed like it was worth writing songs about. Even when the songs are expressions of my own or someone else’s pain, it’s all in the context. The worst example of that would be “You’ve Never Seen Everything,” where the whole song is a catalog of completely horrible things, and the chorus is going, ‘Even though if you’re looking at all this stuff, you haven’t seen everything. There’s good stuff, too. The light is there too.’ I probably won’t write too many songs that go that far in that direction. But it’s there. It’s what life is all about, so it should be in the song.

Did you say ‘when the song is ‘given to me’?

BC: Yeah. I don’t go looking for them. I try to maintain an attitude of receptivity, but the ideas come when they come, and I feel like they’re gifts. Intention goes into it once there’s an idea, once something starts to feel like it’s going to be a song, then I work on it consciously. But otherwise, it’s a matter of waiting for that gift.

Do you feel like you need to train yourself to come from a place of positivity with all these things that you’ve seen and experienced?

BC: Well when I went to Iraq, for instance, I went hoping I would get a song. I didn’t. I did end up with a song, but it’s a little forced. It wasn’t as much of a gift as it was me pushing the issue, too, because I really wanted to have a song about being in Baghdad. There’s been a few other occasions where I’ve done that. It never works as well as when I just wait for it and let it happen. I’m not sure I would have got a song if I hadn’t pushed it, and so, whatever, it all comes out in the wash.

But with the trip to Afghanistan, I didn’t expect to get the song out of that, but I did. “Each One Lost” came out of that trip, and that was a gift, totally. It was a painful one, because the occasion that inspired it was a sad occasion. But the gift was there, regardless of that. And it isn’t always fun. I mean, “Rocket Launcher” was not fun. It wasn’t fun to write, it wasn’t fun to hear the stories or be in the situation that set it up. It’s never fun to sing it. But it seems necessary. If you’re a journalist, you’re someplace close to report on a situation, and you’re not going to just report on the things that feel good. You’re going to report on what you see. And for me that’s the same thing.

Does it take effort to find that place of love to anchor those things in? It seems like that would be a challenge in those situations.

BC: Sometimes it is. I think as time has gone on, it’s become less difficult. Central America was the first time I’d been in a war zone, and it was… it was pretty shocking. I didn’t see action or anything like that. I didn’t stumble over dead bodies or whatever, but I was among people who did do that. In an atmosphere where violence could unfold anytime, the feelings run pretty intensely in situations like that. All kinds of feelings—the good ones, too. Because love really comes to the surface in a situation where all the people you’re sitting with may or may not be alive tomorrow. I mean, that could be true anytime, anywhere. We don’t know who’s gonna die when. But in a war zone, that’s really front and center.

There’s this sense of kind of … camaraderie is not quite the right word, but it’s something like that. That’s too light a word. But there’s a sense of shared experience people are willing to extend to each other. In those situations, of course, those aren’t the people that are about to shoot anybody. That can be negative, too, because that same sense of us as a group can be directed in a hostile way towards someone else. Sitting in Managua, the war wasn’t right there—the war was off in the countryside—but there was just this warmth that was readily available, because the big concerns were the appropriate ones: life and death, and how we get along. People were thinking less about their—this is supposition, I didn’t ask anybody what they were thinking about—but it seemed as if people were thinking less about their immediate concerns and more about the fact that we’re all alive in the same place at the same time. At the time, I remember thinking, ‘This is how journalists get to be war junkies.’ Because it’s exciting. This warmth, this ease of forming—not deep friendships, because you don’t know these people. But the sense of being chummy with people and everybody accepts whatever—it’s an attractive feeling that it could be addictive if you did enough of it.

Sure. Well, and that fragility is really apparent in those situations. Aside from being a war junkie, how do you keep that feeling with you, when you’re not in those situations of imminent danger?

BC: That’s a good question. For clarity, I don’t think I’m a war junkie, although I certainly had those experiences.

But I’m sure they’re out there.

BC: There’s an attraction to that stuff, but it’s also tempered by fear. Am I going to go into a situation where I’m actually gonna get shot at? I prefer not to do that. It was always a possibility, but a fairly remote one, in the circumstances in which I’ve done that kind of travel. Maybe not remote, but lower on the scale of probability. I wouldn’t seek out that situation particularly, unless there was some real compelling reason. But something just inherently risky and that’s all it is? I’m not that kind of person. I’m not an adrenaline junkie like that.

But how do I maintain that? Over time? Again, if you experience that enough, and you live through enough stuff … I guess it matters that I’ve held that in front of me as a desirable part of life like that. If you don’t think about it, maybe it doesn’t work the same way. I don’t feel like I have goals, but I recognize that there’s a way to live and a way not to live. Practicing that over time eventually gets you to a place where you can be more open to that kind of stuff. That doesn’t rule out the ability to get angry at things that make us angry. But the anger is less inclined to take over than it might have been when I was younger.

That is one of the gifts of time and perspective, isn’t it? So along those lines, thinking of one of the more recent songs “To Keep the World We Know,” I was curious: what about the world we know do we want to keep and what do we want to let go? What do we have to let go? Do we want to keep the world we know?

BC: [laughs] The point of phrasing it that way is that, we’re confronted with more than a possibility of finding ourselves in a world we don’t recognize. And what are you gonna do with that? And not in a good way. It’s not like we’re suddenly going to find ourselves going through the pearly gates and walking on the streets of gold. What do we do with that? It’s going to be that life has become extremely difficult for most of us. And then what? So? That’s what I’m thinking in that song. There’s lots about the status quo that is not worth keeping, but it’s hard to know how to get rid of that without getting rid of the good stuff, too. So, with the complicated prey-slash-predator creatures that we are, it’s hard to step away from that.

Sometimes this is a good thing and maybe sometimes it’s not—separating the art from the artist, trying to separate the musician from their life or their politics. Sometimes that’s a goal. Sometimes we want to be able to appreciate someone’s art or music without thinking too much about the person and their feelings and their political views and perspectives. But I think in your case, that’s probably not the goal. Do you find that it’s hard for some folks in your audience to separate those two? Or maybe they try to and it’s not really comfortable for you?

BC: I don’t think about it much one way or the other. I think there’s a tendency for people who are at a certain distance to conflate the art with the artists. It happens with anybody that stands up in front of the public—they become larger than life and people read more into what they say that might actually be there. Or the image they project—sometimes the image is intentional, sometimes it’s just what people put on you.

That happens to me, to some extent, but in general the songs come out of my brain, my life and experience and feelings. And I try to have them be truthful. That said, there’s a lot about me that doesn’t go into songs, certain truths that I don’t think I really want to share with people. So you’ve got to allow for that.

If you think about Bach, nobody cares what his politics were. He just wrote all this beautiful music. I don’t know anything about his political views, if he had any. I think in the era in which he lived, if you were too loud in expressing political views that were not compatible with the authority around you, there’d be a terrible price for that. That would be true in Putin’s Russia. It appears to be, anyway. So you step away from politics. In the Stalinist period, in Russia, there was great music composed, too, where you really, really couldn’t take any chances. If you listened to Bertolt Brecht, you know, because of the content of what he wrote, what his political attitude was. But there it’s explicitly part of his art. That happens with people too, but I don’t know. I think if you live long enough, and work for over a long enough period, you’re gonna go through phases of understanding and phases of interest, and just be drawn into different areas: I’ve done a whole bunch of that, and now I want to do something else. That is going to affect how people perceive you and may not be directly related to what’s going on in your physical life at any one moment.

Yeah, and I’m thinking specifically of the spirituality aspect of your music and the political aspect that maybe for some people don’t line up in the same way that they do for you. I think that’s a challenge for folks sometimes. I know they’re part and parcel in your view, and in the music that you write and the messages you share, which I think is wonderful, but I think that probably is challenging for folks sometimes, who think, “I’m absolutely on board with this piece, and I just can’t quite reconcile with my own worldview.”

BC: The people who only associate me with “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” are divided into camps, basically. There’s the ones who think that’s cool, and the ones who hate it. I hear from both, and I’m aware of both, but that’s one song out of 300-odd songs that I’ve written. It came from a specific time and place in my life and in the lives of the people that I was with at the time. If I went to Central America now, I might write a song that had as much of a sense of outrage as that song does. But it wouldn’t be the same song, and it wouldn’t say the same thing.

The same would be true if you’re listening to “Wondering Where the Lions Are.” It’s a cute song, it may even be a good song, unless you actually listen to the verses. It’s as much about death as all the rest of my songs. It’s light. And it would be too bad if people thought that was the only kind of song I wrote. The same thing is true with “Rocket Launcher.’” There’s a whole lot of other stuff there, if you’re interested enough to pursue it. Don’t judge me by that one song. But I don’t take it back, either. I was there. That’s what I felt. It was the ease with which I felt that outrage that I wanted to share with my peers, who don’t experience stuff like that, or had not at the time. ‘Don’t judge people for taking up arms, if you don’t know what they’re faced with,’ was the undertone of that. I’m not suggesting that taking up arms is a desirable move to make. I think there are times when you can’t avoid it. That was what I wanted to share with people. I’m not a pacifist, because I think there are those occasions. But I think that peace is better than war, and love is better than hate. Most of what I have sung, and maybe will continue [to sing], tries to say that.

I’m thinking also of songs like “Call It Democracy,” which is one of my husband’s favorites. It came to him pretty early in life and was pretty influential in the way that he thought about and viewed things on a global scale. I don’t know if you would take any of that back, either, but it still seems to me a very powerful and still very pertinent commentary.

BC: I wouldn’t take it back. I think there’s more to the world than what that song says, but I think what it talks about is real. And it hasn’t gotten any better. Specific details change from time to time, but clearly it’s the economics of The Forever War, more or less. We didn’t think of it in that language when I wrote it, but it was the beginning of globalization, and I was seeing and hearing about the effects of it from the people who are being directly affected by it. I put that in the song, because you go to any place that was—whether it was Nicaragua, or Jamaica, or anywhere in Africa, or, you know, in a whole lot of other places—you can see the dark side of all that stuff, of the way we live. People who live there see it, too. They know exactly what the cause and effect is. Some of them have something to gain from it. Their leaders often have a vested interest in making deals with the developed world. But the benefit of those deals doesn’t go to the people. It goes to the actual signatories to the deal. That is a situation that is to the benefit of the corporate world. That hasn’t changed. So no, I don’t take it back or anything. I sing it once in a while, and people like it.

You can certainly disagree with any of these statements. I mean, people have different points of view. People who are among the ones that gain from the stuff… I mean, part of the point of “Call It Democracy,” of airing that kind of thought is, in North America and Europe, we’re all beneficiaries of this unfair system. And we should know that. You don’t have to go out and change anything. We might like it. But you should know where your stuff comes from. I still feel that way. But I don’t feel like I have to keep writing that song, though. There’s other things that jump up—some joyful and some not—that also need to be written about.

And that’s all part of being that witness, right? Of being that correspondent, sharing that experience and documenting and putting it out for better or worse? It’s still an experience that was very real for the folks that you were with.

BC: Yes. And for me, yes.

I have one more question for you: I’m looking at a very long, incredibly long list of awards you have received: Juno Awards, certified platinum records, Hall of Fame entries. What recognition has meant the most to you?

BC: Certainly not the music business awards. They’re all very nice, and the way I was appreciated by a number of people—that’s very gratifying. But it doesn’t go very deep. The Order of Canada, I think it’s probably the most meaningful way to be recognized. The honorary degrees are—I have a bunch of those now, and I’m about to get another one—those occasions are sometimes kind of fake. You know, you have a convocation, you gotta get somebody to speak at it. Sometimes there’s a deeper sense that the honor being bestowed is heartfelt. I got an honorary law degree in the same year, the same spring that my wife was graduating from law school. That was, that was pretty cute.

Awkward!

BC: Because she had slaved for three years to get this piece of paper, and I got one handed to me. But I got a doctorate in theology, that actually really meant something. Coming from Queen’s University in Ontario. That’s a couple of examples of probably the two things that actually did mean the most, of all those awards.

The Order of Canada Award—that’s a lifetime achievement award?

BC: It’s not exactly that. It comes from the government. There’s a committee that decides this year who should be included. They can induct a certain fixed number of people each year. They look around the Canadian scene for who’s contributed to the benefit of Canada. To be included that way—there are now several hundred people in the Order of Canada, maybe even 1000. It’s not business related—it has nothing to do with how many records I sold and stuff like that. I mean, indirectly, it does, because if I hadn’t, if nobody ever paid attention to me, I probably wouldn’t have been on the radar.

But to have it be seen as a contribution to the country is meaningful to me in a way that being feted for being a star of some kind is not. When I started, I thought being a star would be the worst possible outcome. A star quote, unquote. Just that term was offensive to me, because it seemed to me that anybody who’s seen as a star is not seen as a person. And I didn’t want to go there. I tried so hard not to have the kind of star image for the first few years I was doing this. But you can’t escape it. People are going to invest you with this larger-than-life thing, no matter what, if they pay attention to you. So, I gave up on that notion. But it’s so much more meaningful to be recognized for something beyond that.

Sure. Well, for someone who’s so focused on storytelling and sharing and contributing and giving back, I can see how that would be an outstanding moment of recognition.

BC: Yeah, it was cool.

Photos: Daniel Keebler

April 22, 2024

Las Vegas Weekly

Singer-Songwriter Bruce Cockburn Lands At Myron’s This Week

by Brock Radke

Local music lovers who follow the wonderfully distinct programming at Myron’s at the Smith Center are in for a rare treat this week when Canadian Songwriters Hall of Famer Bruce Cockburn makes a tour stop Downtown. The award-winning folk, jazz and rock artist—and remarkable guitar player—is making the rounds behind last year’s acclaimed O Sun O Moon, his 27th album which was recorded in Nashville with longtime producer Colin Linden.

It’s been long enough since Cockburn played Vegas that doesn’t remember where he played here last, but the 78-year-old legend remains a road warrior, recently finishing a series of shows in Italy. He’s toured Europe frequently during his long career, “and some aspects of those shows have been pretty politically charged,” he tells the Weekly. “When I started in Europe in the ’80s … it was very volatile in terms of street politics in those days, fascist terrorists blowing up train stations. It was kind of a wild scene.”

Cockburn is often categorized as a folk artist and his songwriting has frequently addressed human rights and environmental issues. But whether audiences are connecting to the meaningful lyrics or the articulate music, they are always connecting.

“It’s a whole different experience playing to an audience not fluent in English,” he says. “Some years ago a guy in Italy was telling me after the show, ‘I don’t understand anything you say, but I love your music because it makes me feel so calm.’ And that show included [songs] ‘Call it Democracy’ and ‘If I Had a Rocket Launcher,’ some fairly inflammatory stuff.”

The concert at Myron’s will be a solo show, just Cockburn and his guitar, “so if you don’t like a show that doesn’t have drums, don’t come,” he jokes. It may sound minimalist, but the uninformed should check out a live clip on YouTube to learn how Cockburn creates undulating layers of music all by himself, and hones in on his award-winning lyrics at the right moments.

“I’ve always felt free to write about any subject that came up … but people noticed the political songs early on and I was sort of defined that way in the minds of those people,” Cockburn says. “I don’t see that as being put in a box, but maybe what could be called a box is that I offer people songs where the lyrics matter. That approach … isolates me from a certain category of artist and a certain demographic, but lots of people want to be entertained by something that asks a little bit of them. That’s my crowd.”

Photo: Daniel Keebler

April 16, 2024

Grateful Web Interview With Bruce Cockburn

by Sam A. Marshall

In May 2023, Bruce Cockburn – the highly prolific Canadian singer-songwriter active as a performing and recording artist since the 1960s – released his 38th studio album, O Sun O Moon. Then, not long after that, he began an extensive tour in support of the album that – extending to nearly 50 dates so far – has continued into the present year.

Between late April and early July this year, Cockburn will be logging nearly 25 new shows of his soul-stirring live performances in the U.S. and Canada. And since those dates only cover a clutch of cities in the Southwest U.S. and in Ontario, it’s reassuring for those of us most mindful of the passage of time that the now-78-year-old artist is charting out another run of North American shows for late fall.

Practically on the eve of this next run of dates that begins on April 24, in San Luis Obispo, CA, Grateful Web was most fortunate to have a personal conversation with Dr. Cockburn about the record and upcoming tour. (This took place on April 9, coincidentally the day after the great 2024 North American total eclipse.) This highly-awarded songwriter and performer – and, in fact, a holder of three honorary doctoral degrees in music – touched upon some his personal creative processes, his way of looking at the world and even a bit of the mysteries of existence – all ingredients in the making of O Sun O Moon.

When I attended one of Cockburn’s shows last year in Cincinnati, Ohio, still early on the 2023 tour, O Sun O Moon was certainly the main entree of songs on the menu that night. Yet, there was a good number of recognizable, fan-favorite songs and a few surprises on offer. Over the year since the album’s release and beginning of the tour, faithful fans of the master musical storyteller and guitarist have had a chance to become more deeply familiar with the new album. And – to my ears and mind at least – it may very well become as cherished as any of his most classic collections.

Although I was introduced to Cockburn’s music in the later 1970s, not long after his first few albums had been released, I’ve admittedly drifted in and out through different stages of his career. While I was off following other genres and more rock-oriented artists, I’d keep my ear cocked for what ‘progressive’ folk artists such as he and British folk-rock pioneer Richard Thompson would be up to next, even if l didn’t always listen to every album in depth. Initially more of an solo acoustic folk songwriter, he pursued a more obvious electric route with backing bands in the ‘80s, and in the MTV era even reached beyond his core audience with videos for such electrified rock activism songs as “Call It Democracy” and “If a Tree Falls”. Of course, some of that period drew me back. Yet, I’ve surely missed a good many things, so even now I feel as if I’m still catching up with Cockburn.

With my incomplete knowledge of Cockburn’s entire body of work, I’ve tended to gravitate toward his more rock-oriented releases, and a personal favorite is his 2002, You’ve Never Seen Everything. This album deftly balances ballads against some modern-rock grooves such as the rap-spiel opener “Tried and Tested”. And while there are moments of sweetness and light in the folk-style songs, there are more experimental moments, too, like the album’s title track – a chilling, nine-minute, film-noir-soundscape with spoken-word narration that takes the listener on a journey through a dark night of the soul. I also tend to listen more for his instrumentals and expressive, jazz-flavored guitar performances than for his lyrical songs, so I’ve also been highly impressed with his all-instrumental albums, 2005’s Speechless and 2019’s Crowing Ignites, which are both journeys of their own.

Recorded in Nashville with Cockburn’s go-to producer Colin Linden, O Sun O Moon seemingly reshuffles the deck on listener expectations – and mine. It’s an album of sublimely crafted acoustic songs, rich in musical textures, air, and light that never once leave one wishing for more electrical current. Through alternating modes of quandary, gravity, celebration, sardonic humor and emotional resolve, his poetic and minimalist lyrics explore questions of life and mortality, love and forgiveness, and our place in the world.

So, yes, personal themes abound on the album, such as making the best of the time one has left in life (“On a Roll”), the spirituality in everyday life (“Into the Now”) and looking ahead to the next adventure (“When You Arrive” – a joyous New Orleans’ waltz that not only serves as the album’s grand finale but is also a rousing live sing-along.)

In any case, the longtime social and political activist also hasn’t shied away from contemporary issues but allows them a space of their own on the album. One such song is the percolating, roots-y, climate-change tune, “To Keep the World We Know”, which he co-wrote with fellow Canadian singer-songwriter Susan Aglukark. And in the probing song about coming to terms with our fellow man and woman titled “Orders”, the perennial humanitarian seemingly answers the biggest question of all – “Why are we here?” – with unflinching directness.

Front and center, of course, is Cockburn’s warm and knowing but not-always-sweet voice, swathed in musical textures that range from soothing and inspirational to ones with more spit and grit. In fact, you might think that his song “King of Bolero” is a fair impression of Tom Waits. His guitar playing is also exemplary, although it never draws undue attention to itself. And both his vocals and instrumentation are kept good company with a fine ensemble of guest vocalists and musicians. Among these are Gary Craig, Sarah Jarosz, Jenny Scheinman, Buddy Miller, Susan Aglukark, Shawn Colvin and Jim Hoke.

O Sun O Moon is a satisfying emotional experience, from start to finish, and if you’re a longtime fan of this veteran songwriter, then you have very likely already moved it upward – if not all the way to the top – on your personal list of favorite Cockburn albums. If you happen to be still largely uninitiated to his musical universe, then this album – with its Zen-like sense of presence, sage wisdom and timelessness – is an excellent place to start your journey.

“One more time,” Cockburn urges his backing singers onward with a glimmer in his voice on the final, life-affirming refrain of “When You Arrive.” And when he plays it live, the whole audience joins in, shedding even more light into all the dark corners. Now isn’t that what friends are for?

GW: Glad you could make time to talk to us, Bruce. Our phone call seems very timely, since your recent album is called O Sun O Moon, and yesterday we had the total eclipse in the eastern U.S. A nice coincidence! I’m guessing that maybe if you’re near the East Coast right now, you were able to see the eclipse. If you did, I’m curious what your personal reaction to the that was.

Cockburn: Yes, in fact, I’m in Ontario at the moment. It was pretty amazing, actually.

GW: We enjoyed it in our area, too, and we could travel to where totality was without too much effort. Coincidentally, you often deal with imagery of stars and the cosmos in your lyrics, so one of the things I wanted to ask you about is the struggle between darkness and light in your songs. The album title and lyrics of O Sun O Moon seems to allude to that, but then you have a song like “On a Roll”, which seems to imply that maybe the light is winning this time. Would you say that’s true, or is it still always shifting for you?

Cockburn: That’s an interesting question. I haven’t exactly thought about things from that angle. My songs come from a pretty personal place, so, in my mind, they don’t automatically equate with larger philosophical observations. But, to phrase that question another way: “Do I feel myself to be an optimist or a pessimist?” In those terms, then I do tend to go back and forth.