FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

September 28, 2022

Contact: Mark Pucci (770) 804-9555

Acclaimed Singer-Songwriter Bruce Cockburn Announces November 25th Digital Release of Rarities, Along With Three Career-Defining Classic Albums on Vinyl from True North Records

1970 Self-Titled Debut Album, 1997’s The Charity Of Night & 1999’s Breakfast In New Orleans, Dinner In Timbuktu to be issued individually on 180 Gram Black Vinyl.

Listen to Waterwalker Theme | Pre-Order Digital Album & Vinyl Re-Issues

Having sold more than nine million albums worldwide, acclaimed songwriter, performer, author and activist Bruce Cockburn is a member of both the Canadian Songwriter and Canadian Music Hall of Fame, a winner of Folk Alliance’s People’s Voice Award, as well 13 JUNO Awards from more than 30 nominations.

WATERDOWN ON - On Rarities, Bruce Cockburn is finally sharing twelve rarely heard recordings with digital music consumers that were previously only available within the Rumours of Glory limited-edition box set, along with four remastered tracks that appeared on tribute compilation albums dedicated to Gordon Lightfoot, Pete Seeger, Mississippi Sheiks and Mississippi John Hurt.

Rarities will be available on November 25, 2022, on all digital platforms including Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube Music, Amazon Music and Deezer. An advance single, the theme song from the 1983 Bill Mason-directed National Film Board film, Waterwalker, is available to stream now, along with pre-order and pre-save links for the digital album, and details on the musicians, studios, producers and recording dates for the tracks, all of which can be found here.

Also found on Rarities are two songs not on the original limited-edition CD, Rumours of Glory: “Twilight On The Champlain Sea” featuring Ani DiFranco, originally intended to be on Life Short Call Now and used on the Japan-only release, and 1966’s “Bird Without Wings,” the oldest Cockburn demo from his personal vault, later recorded by Ottawa's 3's A Crowd and produced by The Mamas & the Papas’ Mama Cass.

On the same day as the Rarities album is released, Cockburn and True North Records are releasing three albums on 180g black vinyl – 1996’s Charity of Night, 1999’s Breakfast In New Orleans Dinner In Timbuktu and the 1970 debut album Bruce Cockburn, all of which can also be pre-ordered here.

Bruce Cockburn – Rarities - Track Listing:

Juan Carlos Theme

Waterwalker Theme

Avalon, My Home Town

Wise Users

Going Down The Road

The Whole Night Sky (Alternate Version)

Grinning Moon

Song For Touring Around The Stars

Come Down Healing

Mystery Walk

The Trains Don't Run Here Anymore (Re-Mastered)

Ribbon Of Darkness (Re-Mastered)

Turn, Turn, Turn (Re-Mastered)

Honey Babe Let The Deal Go Down (Re-Mastered)

Twilight on the Champlain Sea featuring Ani DiFranco

Bird Without Wings

Bruce Cockburn 2023 Tour Dates:

January 27, 2023 Bing Concert Hall Stanford CA USA

January 28, 2023 Jam Cellars Ballroom Napa CA USA

January 30, 2023 Elsinore Theater Salem OR USA

January 31, 2023 Rialto Theater Tacoma WA USA

February 2, 2023 Royal Theatre Victoria BC Canada

February 4, 2023 Centre for the Performing Arts Vancouver BC Canada

February 5, 2023 Community Theatre Kelowna BC Canada

February 6, 2023 Jack Singer Theatre Calgary AB Canada

February 8, 2023 Winspear Centre Edmonton AB Canada

February 9, 2023 TCU Place Saskatoon SK Canada

February 10, 2023 Burton Cummings Theatre Winnipeg MB Canada

February 11, 2023 Parkway Theater Minneapolis MN USA

February 13, 2023 Hoyt Sherman Theater Des Moines IA USA

February 14, 2023 Rococo Theater Lincoln NE USA

February 15, 2023 Liberty Hall Lawrence KS USA

February 17, 2023 The Armory Ft. Collins CO USA

February 18, 2023 The Armory Ft. Collins CO USA

February 19, 2023 Avalon Theatre Grand Junction CO USA

For further information, contact: USA - Mark Pucci - Mark@markpuccimedia.com

Canada & ROW - Eric Alper eric@truenorthrecords.com

Bruce Cockburn & Ticket Links - http://brucecockburn.com

May 25, 2022

Toronto Globe & Mail

Obituary

Designer Michael Wrycraft created artful album covers and concert posters

by Brad Wheeler

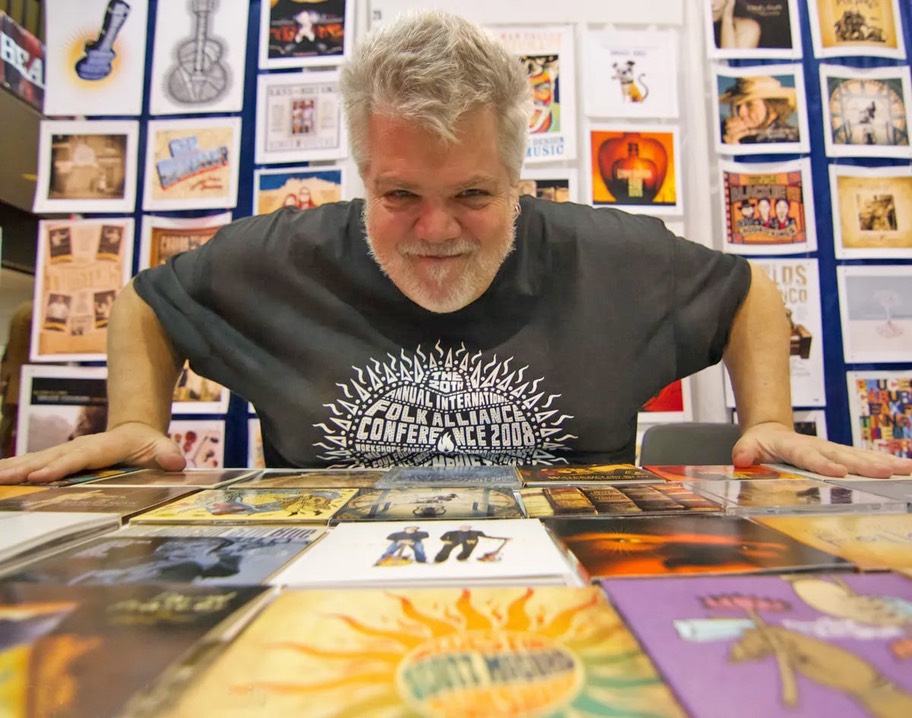

Michael Wrycraft, a Juno-winning graphic designer who created thousands of concert posters and album covers, was a man devoted to music and musicians. He was a collegial presence at the backstages of Canadian folk festivals from coast to coast and embraced life and people with bear-hugging enthusiasm.

A larger-than-life figure with both a combustible temper and a fun-loving demeanour, he was an unsinkable, sparkle-eyed Falstaff who would not even allow a double-leg amputation to slow him down.

“I had an extreme pedicure,” he told friends, five years ago.

Mr. Wrycraft died on May 16 of cardiac arrest at Toronto Western Hospital. He was 65.

He was born in Toronto, Oct. 15, 1956, to sales and marketing professional Norman Wrycraft and homemaker Maureen (née Martin) Wrycraft. By the time he was eight, he had already decided on a career as a commercial artist after watching the American fantasy sitcom Bewitched. The magic that enchanted him came not from Elizabeth Montgomery’s nose-twitching witch character but from her husband, the buttoned-down advertising man.

“The idea of having a job where you get to create things from scratch for people and they pay you really turned my crank,” he told CKAU radio’s Peter North.

At Westwood Secondary School (now Lincoln M. Alexander Secondary School), his hip art teacher allowed students to play vinyl. To be an album designer was a dream job for Mr. Wrycraft, who often brought in Bruce Cockburn records for the class. He would later create 11 album designs for Mr. Cockburn, including 1999′s Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu, which made its way into a Museum of Modern Art exhibit that celebrated the Helvetica typeface.

“I am very much saddened by Michael’s passing, though I expect he would be cracking some wry joke about it if he could,” Mr. Cockburn told The Globe and Mail. “He was the funniest person I’ve ever known, but also sensitive and kind, and a pleasure to work with.”

On the other hand, Mr. Wrycraft was strong-willed and profoundly committed to his artistic inspirations. “You could move him off his position, but, man, you really had to invest in it,” said singer-songwriter James Keelaghan, who hired the opinionated graphic designer for seven of his albums. “It was easy enough to let his curmudgeoness just roll off your back, though.”

Though Mr. Wrycraft studied at Ontario College of Art & Design University and Sheridan College, wanderlust got in the way of a diploma. He had already begun performing stand-up comedy in Toronto when he took off to Los Angeles to pursue an entertainment career in 1982.

In California he found work with an architectural ceiling firm while plugging away at comedy. Competing in a contest at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood in the mid-1980s, he won a free automobile rental. He drove north to San Francisco – and stayed there for three years.

As the manager of the Lusty Lady Theatre, he spent the 1989 San Francisco Bay earthquake in the basement with naked strippers. He told the Roots Music Canada website that he was making $1,600 a week at the time, but that he blew his paycheques on music.

“I basically spent and wasted all of that money,” he said. “I could’ve bought a house.”

By the early 1990s, at the insistence of U.S. immigration officials, Mr. Wrycraft had returned to Toronto. Through an affiliation with fiddler Oliver Schroer he was introduced into the Canadian folk music scene. He became one the most loquacious and outsized personalities within the close-knit community, whether designing CD packages or promoting and emceeing a continuing series of concerts at Toronto’s Hugh’s Room club.

The shows he presented were tributes to songwriters, including his favourite, Tom Waits. Mr. Wrycraft would curate thematic bills of unknown, up-and-coming and well-established musicians to perform the songs of whichever artist was being celebrated that night.

“Sometimes Michael’s shows were train wrecks,” said music publicist Richard Flohil,” and sometimes they were inspired brilliance.”

Mr. Wrycraft won the Juno Award for best album design in 2000 for his work as creative director for Andy Stochansky’s Radio Fusebox. He received five additional nominations over the years for other album designs.

He created CD packages for albums by Murray McLauchlan, Blackie & the Rodeo Kings, Lynne Hanson, Watermelon Slim, Ron Hynes, Lori Yates and many others. He was known for thoughtful immersions into the music and lyrics that resulted in meaningful design work.

“If something touched him, it touched him to the core,” Mr. Keelaghan said. “And nothing inspired him more than to be around people who wrote lyrics honestly or created music from their soul, rather than being part of some music business machine.”

For his 2009 album House of Cards, Mr. Keelaghan told Mr. Wrycraft he envisioned a cover involving a photo of a typical house made of playing cards, perhaps falling apart. Mr. Wrycraft listened to the idea, closed his laptop and said he’d talk to the musician soon. Two weeks later he came back with a concept that was nothing like what his client had in mind. The design, art unto itself, dazzled Mr. Keelaghan.

“I seem to have a sixth sense for creating imagery for people that they wouldn’t have expected but somehow touches them very deeply,” Mr. Wrycraft once explained.

A fan of live music as much as recorded music, Mr. Wrycraft took off on a road trip one weekend with Mr. Flohil and musician Paul Reddick to Woodstock, N.Y., where the former Band singer-drummer Levon Helm held monthly Midnight Ramble hootenannies.

Preparing for the journey, Mr. Wrycraft hid three Saran-wrapped marijuana cigarettes within himself in a private spot where no border guard would care to look. After successfully clearing the border, he then needed to clear the weed.

The trio stopped at a Bob Evans restaurant, where Mr. Wrycraft immediately headed to the restroom to delicately retrieve the drugs. “All of a sudden, everybody in the restaurant is hearing Michael yell from the john,” Mr. Flohil said.

What had happened was that after Mr. Wrycraft had expelled the dope, he naturally stood up. But it was an automatic-flush toilet – the stash was instantly gone in a swirl of water.

“There was a deep sadness to his howl that I’d never experienced before nor since,” Mr. Reddick recalled.

If Mr. Wrycraft could howl with the worst of them, he could laugh with the best. He was a burly, baritone-voiced raconteur who easily sucked people into his orbit with outlandish stories and a buoyant vibe. “He was an entertainer, and entertainers want to make people happy,” said Heather Kitching, a radio freelancer and folk-scene veteran.

In 2017, Mr. Wyrcraft lost his legs to osteomyelitis. Though he would require a wheelchair for the rest of his life, he refused to let the setback defeat him. “I’m not shaking my fists at the world,” he told The Globe. “None of this affects the best part of me – my humour, my optimism.”

But it did affect his ability to host his singer-songwriter tributes at Hugh’s Room. The tiered venue – “a festival of staircases,” he quipped – was not wheelchair-friendly.

Though the club wasn’t accessible, Mr. Wrycraft still was. In recent years he held court on a corner just outside Toronto’s Trinity-Bellwoods Park, sitting and reading in his wheelchair while talking to friends and passersby. So common was his presence there that he showed up on a Google Street View image of the corner.

Suffering from congestive heart failure, Mr. Wrycraft spent his last days in hospital. On Facebook, he signed off in his typical untroubled way:

Life is crazy

But it is also beautiful

I have had a good run

Mr. Wrycraft leaves three younger siblings, Kim, Kevin and Karen Wrycraft.

May 19, 2022

The Mockingbird

From the Success or Failure issue

“Big Circumstance” Has Brought Us Here - An Interview with Bruce Cockburn

by Ben Self

Despite growing up in what he calls “a typical 1950s Canadian middle class household” in suburban Ottawa, Bruce Cockburn has done his share of wandering. He first became a star in the Canadian music scene in the early 1970s, winning the JUNO for Folksinger of the Year three years running. In 1974, he converted to Christianity and went on to release several albums with overtly religious themes. Among the best of these was In the Falling Dark (1976), which includes stirring songs of faith like “Lord of the Starfields” and “Festival of Friends.” While he never quite embraced the label of a “Christian” musician, and has often struggled with the legalism and reactionary politics of much organized religion, the push-and-pull of Christian faith has remained a central thread in Cockburn’s work and life.

Following the dissolution of his first marriage the in the late 70s, Cockburn made a conscious decision to “embrace human society” and moved to Toronto, Canada’s largest city. His musical style soon became heavier and grittier, and his lyrics darker and more politically-charged. He was also deeply impacted by his travels abroad, especially an intense Oxfam-led trip to Central America in 1983. These influences culminated in a “North-South trilogy” of albums that included the bracing hit Stealing Fire (1984), which featured two of his career’s biggest singles: “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” and “Lovers in a Dangerous Time.”

After an exhausting decade that ended in a period of writer’s block, Cockburn reinvented himself again in the 1990s, shifting back to more acoustic, introspective material. His output from the period included deeply meditative albums like The Charity of Night (1997), which captures the world-weary wisdom of middle-age in songs like “Pacing the Cage” and the final track “Strange Waters.” The latter, for example, functions like a grungy, latter-day psalm:

You’ve been leading me

Beside strange waters

Streams of beautiful lights in the night

But where is my pastureland in these dark valleys?

If I loose my grip, will I take flight?

Now in his mid-seventies and settled in San Francisco, Cockburn is still asking the deep questions and watching for those “inexorable promptings” of the Spirit, or what he sometimes calls “Big Circumstance.”[1] To the delight of his fans, he continues to tour and release new studio albums, including the soulful Bone On Bone (2017), for which he won his 13th JUNO award, and the rich instrumental album Crowing Ignites (2019). Below he shares about both his musical and his religious journeys, his complicated relationship to success, along with insights on the creative process, and much more.

Mockingbird: To get us started, I’d love to hear a bit about your musical origins. What kinds of things did you listen to growing up?

Bruce Cockburn: Well, the first music I remember being aware of was the stuff my dad used to play. When I was born, I think he thought that he would educate me, so he enrolled us in the record of the month club. Every month we got a nice classical album in the mail, and we’d have to sit and listen to it. Some of them got listened to only once, some of them more than once. But he kept them, and I was able to rediscover those records when I was older.

Anyway, later on I heard all the stuff that was on the radio at that time — Bing Crosby, Perry Como, Bobby Darin — as well as the first rock-n-roll. It was listening to that first rock-n-roll when I first got really interested in music. I was a huge Elvis Presley fan.

M: Is that when you started getting into the guitar?

BC: Yeah. The explosion of rock-n-roll all started around 1956 or so, and I started playing guitar in 1959. My parents were initially concerned about the association of the guitar with rock-n-roll — and the association of rock-n-roll with leather jackets and switchblades — so they were worried. But they said, “Look, we’ll support your guitar lessons if you promise not to get a leather jacket and grow sideburns.” And it was easy to make that promise. Like, what the hell! I couldn’t even grow sideburns.

So I started taking guitar lessons, which exposed me to jazz and Les-Paul-style pop country guitar. Then I started studying composition on my own, and I eventually got more into folk music — country blues and ragtime, that kind of stuff. That period of anybody’s life tends to be so full. There’s this accumulation, this constantly shifting exposure to things, because you’re young, and you’re soaking it up like a sponge. By the time I got out of high school, I wasn’t good at anything, but I had a very well-rounded view of musical possibilities.

After that I went to music school in Boston for a year and a half, before dropping out. But I came out of that with an even broader view. By then it was the 60s, and we were listening to Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles. And jug band music. Anyway, all of that went into me and formed this big musical soup out of which, eventually, songs came.

M: When you first started playing in bands in the mid-60s, you were playing mostly psychedelic rock. But then your initial solo work from the early-to-mid 70s was totally different. It seemed to have a kind of earthiness and acoustic purity that, at least to me, evokes the wild spaces of eastern Canada. Does that resonate at all?

BC: Yeah, I’m glad you could hear that in the music. One of things that maybe distinguishes a lot of Canadian songwriting from American songwriting, say, or British songwriting, is that sense of space. I think you can hear it in Leonard Cohen, in Joni Mitchell, in Neil Young — it’s there even in his electric stuff, I think.

In the 70s, I was focused on the natural world and the spiritual doorway that that seems to represent. I loved the way in which one’s own spirit feels enlarged. You find yourself in a setting where human presence can be either ignored completely or just isn’t there. From my experience, the soul expands, seems to touch the spirit of the wilderness. And that was a big part of my childhood — spending summers in Algonquin Park, canoe-tripping, portaging over horrible mud patches, surrounded by that wild Precambrian shield landscape.

M: You had a conversion to Christianity around 1974, which of course showed up very prominently in your songwriting. But you once said something interesting about that time in your life: “I was trying to figure out what it meant to be a Christian now that I’d made this move, and the first thing you try to do is to find what all the rules are, and then you try to obey them. That makes you kind of a fundamentalist… But in the end I was completely unsuccessful at being a fundamentalist.” What did you mean by that?

BC: When I first started thinking of myself as a Christian, I listened to the loudest Christians, the fundamentalists. I mean, I’d gone to a very bland United Church for a while growing up — the sort where you have to put on your scratchy gray flannels, you know — but that hadn’t made a big impression on me. So now here I was in the mid-70s, calling myself a Christian, and I thought: I’m supposed to figure out what that means, and how to be a Christian in the world. And the loudest voices were the ones on TV.

So I started listening to Ernest Angley and the Bakkers and these other TV evangelists, and I tried to give them the benefit of the doubt, but I wasn’t successful. The version of Christianity that they were presenting was just ridiculous. It didn’t stand up to any kind of scrutiny that I could bring to it, emotional or intellectual. And there were other voices that were a little more subtle but in the end weren’t much better.

I’d buy these books that were by highly-reputed Christian writers or whatever, and you’d get all this BS. There was this one guy who kept going on about how minor key music should be banned because it makes people depressed. I mean, give me a break! That has nothing to do with Jesus. Sounds more like Hitler.

So it didn’t take very long for me to lose interest in that stuff. But even a decade later, I would still occasionally watch the TV guys, thinking there might be something there — that maybe I’m supposed to watch this today, maybe there’s something in there for me. Because I do think that things work like that. Quite often the things we’re exposed to have some purpose to them — it’s what I called “Big Circumstance” later on — where it’s not random but it’s not exactly preordained, either. It’s like the whole cosmos is this kind of jigsaw flux and you’re in it, and you’re moving in it. I’m not even sure what it is. You could call it the “will of God,” but it might not be that simple.

But anyway, once in a while I would watch the TV evangelists. Actually, occasionally I still do, if I’m in a hotel somewhere, you know, and I turn on the TV and on comes one of these characters, I might listen to them to see if there’s anything there. Generally there isn’t, but once in a while there is. Once in a while something turns up that’s valuable.

At one point in the 70s or 80s, I saw a very skeptical — you could say cynical — Canadian TV journalist interview Mother Teresa, and it was unbelievably great. Mother Teresa burned off the screen. She just was so absolutely real and free of any kind of pretense. It was an impressive thing to witness. I don’t remember what she said, but the way she came across made a big impression. Those kinds of things happen.

In the end though, my flirtation with that stuff turned out to be just that. I realized, well, these televangelists don’t really know what they’re talking about. Or maybe they do, but they’re not really communicating the part that’s true about what they know. They’re communicating “send me money” and all kinds of other stuff. So through the 80s I still thought of myself as a Christian, but I was less and less inclined to go to church.

When I moved to Toronto at the end of the 70s, I never found a church that I felt at home in. And I found myself mostly among people who were not believers, because I’d decided it was time for me to embrace human society in a way that I had not previously done; and in the 80s, humanity replaced nature as my focus. I mean, I still had the connection to nature, but as a source of energy and an avenue of spiritual expression, people became more the scene for me.

I got involved in the kinds of supposedly “political” stuff people say I got involved in — and I wrote songs about those things. That shift was natural; it wasn’t planned. Moving to Toronto and embracing human society was a deliberate choice, but after that, everything just flowed.

M: For people who are new converts, I think there’s often this sense that you have to live up to some strict Christian standard and follow all the rules, which can be very self-defeating. Did you feel that way — like a failed Christian?

BC: I certainly did at times, and I still do, I think. Not severely. I’m sure other people have felt it worse. But I don’t pay nearly enough attention on a day-to-day basis to my relationship with God. I talk about it a fair amount, but I don’t do much about it. But then, once in a while, I do do something about it, and I’m reminded that it exists, and that it’s really happening. And it feels pretty darn good when that happens. But, interestingly, one of the first tests of that for me came when I got divorced. A lot of stuff on the Humans album (1980) is about that.

M: Like the song “Fascist Architecture”?[2]

BC: Well, yeah, “Fascist Architecture” and “What About the Bond.”[3] Those are kind of break up songs. But they’re also liberation songs. I was working through a bunch of unexamined assumptions. Like: we got married in the presence of God, made promises in the presence of God, and we were breaking those promises. What did that mean? Turned out God seemed more interested in us growing as people, and we hadn’t been doing that together. I think both of us have done a lot of growing since then.

M: Did you feel wracked with guilt, though?

BC: Yeah. But I think guilt is an excuse for not feeling like a failure. It’s easier to look at the guilt than at the failure — at what should I have done differently? Where do I go next? I mean, guilt is a kind of demonic implant that gets in the way of taking that next step with a clear mind. So I think guilt is to be resisted, unless of course you’re genuinely guilty of some heinous crime. That’s different. We’re talking about spiritual or emotional stuff here.

M: Does faith help with guilt and shame?

BC: It’s supposed to. I mean, Jesus kind of says that. Like, I’m here for you. You’re never going to get it right, but I did, so lean on me. That, to me, is something that a lot of the church — the body of Christ — doesn’t pay attention to. There’s so much shaming.

But the message of Jesus is like a hammock you can relax into. It’s love and forgiveness. And it’s not just the Christian part of the Bible that talks about that — the Old Testament talks about love and forbearance; it runs right through. But Jesus exemplifies it in so many ways and makes it so clear, yet people still miss the message.

M: In the late 70s and early 80s you had some breakthrough hits that garnered you acclaim well beyond Canada; at one point you even played on Saturday Night Live. What were the blessings and the curses that came with that kind of success?

BC: It came about in a strange way. “Wondering Where the Lions Are” was the first actual national hit I had in Canada, and it got a lot of airplay in the United States — it was on the Billboard charts, and that’s what we ended up doing on SNL. But the song that people remember more than that one was “If I had a Rocket Launcher,” which came around 4-5 years later. It wasn’t as big a hit, but that’s still the one that made a bigger impression, which is odd because that one isn’t really a typical Cockburn song at all. It was such an anomaly.

In the United States people didn’t know my history. I had a relationship with Canadian audiences, but I didn’t have that relationship with the American audience, and so I got labeled a “political” singer because of “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.” I mean, yeah okay, that political message is in there,[4] but I don’t like to be categorized, and I don’t like pinning down things that don’t need to be pinned down. Early on in Canada, after my first three albums, I was getting typecast as a nature guy, and I resented that. “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” did the same thing later on in a different direction. I don’t like being called a “Christian” singer, either, even though that’s true. But I don’t want my audience to only be Christians who only listen to Christian singers.

I’ve tried so hard not to have an image, and maybe I made more of it than I needed to. I didn’t want to be a “star,” because that’s a falsehood. It’s a public construct. I wanted to be me. So I went out of my way to avoid all sorts of things that I thought might lead to the creation of the “star” construct. And I was fairly successful at that, except that I got the image of being a guy who went out of his way to avoid having an image. So, that became its own kind of trap. And the lesson there was: well, you can’t avoid this. As soon as you stand up in public and do anything, that process begins. And the more you do, the more it happens.

But the success I had also came with a lot of perks. There was more money, more gigs, better traveling and working conditions. You know, all that stuff came to me, and because of the public visibility that went with that, I got invited to do lots of interesting things — like go to Nicaragua and Nepal and other places where stuff was going on that was meaningful to me. In some cases, it provided material for songs — I mean, that’s not why I went to those places, but it was a side effect of being there, and it certainly deepened my understanding of people and how people work and what we’re capable of, in all directions.

M: In the late 80s, if I’m not mistaken, you experienced a period of writer’s block. What do you think caused that?

BC: Burnout. That’s what I felt at the time. I went for about a year and a half where I didn’t write anything — I didn’t have any ideas, or any motivation. I had the desire to write but nothing making it happen. And for half of ’88 and all of ’89 I felt like that. And I thought, this has been a decade of such intense travel for me, and travel in some places where there’s a lot of pain, and even though it wasn’t my pain, you still soak up some of it. And I just felt like I needed a break.

But my actual first thought was, “Well, this is the end. I’ve got to think of something new to do, because there are no more songs coming.” I thought about enrolling in art school, because I’ve always liked graphic novels, and I had some drawing chops when I was a little kid. But then I decided that before I did anything too radical, I should just take a rest and step away from it all.

So I declared myself on sabbatical for the year 1990, and you know, my sabbatical hadn’t even started yet when I started writing songs again. For Christmas, my then-girlfriend and I and my older daughter — who was 14 then — we went to a dude ranch in Arizona. It was a magical experience in lots of ways, but sitting there I wrote “Child of the Wind.” And all it took for the creative process to start again was the declaration to myself that I was free from whatever encumbrances I thought I had. And it came back. And on I went.

I wrote the songs that are on Nothing but a Burning Light (1991) through that period. And I ended up having a lot of fun on my year off. Riding horses and shooting — that’s mostly what I did. But I did a lot of playing music for myself, too, with no ulterior motive.

M: I listened to a recent podcast you did with Les Stroud and one of the things you guys talked about was the nature of creativity. You said you felt like some of your creative impulses basically come from God — that God is involved in the process, always “stirring the pot.” In crafting songs, what is the relationship for you between grace and effort?

BC: Hmm. First the grace, then the effort. And the effort is more like translation, in a way; it’s analogous to that at least. It’s a question of taking that initial idea — which is a gift, I find — and then kind of wrestling it into something that makes sense musically and lyrically, and will be as compelling as it can be for whoever hears it.

M: It sounds like Jacob wrestling the angel of God in the night.

BC: Haha — a little bit like that. Except you come away with something that might be a win.

M: Not a busted hip.

BC: Yeah. It’s a little bit hard to articulate. But the feeling is in the heart. And the process varies from song to song. Some songs require much more labor and some songs not so much. Sometimes a single idea will trigger an immediate flow of associations that shape themselves into a song, and other times that single idea will have to sit around for a while before you find something to connect it to, to develop it.

And some of these things I don’t look at too hard — I don’t try to imagine what God might want from these things. In certain songs, it might seem obvious, but other songs are just songs. They’re reflective of my life in various ways, of various attitudes and so on.

M: That’s interesting. What happens if the song-writing process doesn’t go well?

BC: Even if I fail to get a good song out of what should have been a good idea, I don’t really see it as failure as much as just a blind trail, a false start. Because if it’s a real thing, it will come back around at some point.

I’ve never put much pressure on myself to produce. But I sometimes feel a visceral need to write. And when I don’t write for a long time, then I feel frustrated and kind of constipated, and it’s a great relief when stuff starts to come. For me, the control, and how “well” I do with a given idea, is all beside the point.

One other thing I notice in myself is a desire not to repeat myself. I don’t try to duplicate the songs that were “successful.” I am aware of certain things that I can put in a song that are going to make it more or less appealing to people, and those are creative choices to be made. But you see it all the time — certain artists who make one great record and then try to do the same record again, and it’s just not a good idea, you know?

M: In 2013, you started regularly attending a church again for the first time in several decades. How did that come about?

BC: It’s interesting, you know. It was one of those inexorable promptings. It was “Big Circumstance” at work. But it started with a tragedy. Sadly, a neighbor of ours that my wife was quite friendly with died in a house fire. That pushed her into looking for the meaning behind things like that, and looking in the direction of God for some understanding.

I have my own experiences and thoughts about that sort of thing, but you know we weren’t churchgoers then. I hadn’t thought of myself as a churchgoer for decades, and neither had she. But in the course of that search on her part, she discovered the San Francisco Lighthouse Church. And she kept inviting me to come with her — you know, like, “You gotta come check this out, the pastor’s really great, and there’s great music.”

M: Great music always helps.

BC: Yeah, but I resisted it for quite a while, and then I finally caved and went, and I just kept going after that. It was like, the minute I walked in I felt surrounded by love. And that’s something you don’t want to pass up.

M: For many people, these have been pretty dark and stressful times — with the pandemic, environmental crises, all kinds of intense political and social stuff. So in times like these, what gives you hope?

BC: Well, my relationship with God doesn’t depend on any of that stuff you mentioned. Of course, you can be distracted by external things of whatever sort, but really, if that relationship is where you’re focused, then the other stuff is tolerable in one way or another.

But, I mean, there’s still lots to worry about. We’re confronted with all sorts of precarious tipping points around us. We’ve got to be really careful where we step — as a culture, as individuals, even as a species. And it’s not clear to me that those steps are going to be taken the way they need to be. But that said, as individuals, we still have that relationship with the divine to keep us focused.

M: And free?

BC: Free! Yes. I mean, that’s real freedom. Never mind protesting about mask mandates or whatever. If you think your freedom is really about not wearing a mask, you’re already screwed.

M: Right. I love that line from one of the new songs you posted online recently: “Time takes its toll, but in my soul I’m on a roll.”

BC: I felt good about that line. But you know, it’s an old guy writing that song.

M: That’s true. Old and wise.

May 11, 2022

Christian Courier

RADICAL HOPE

Fifty years later, is Bruce Cockburn’s music still relevant?

by Brian Walsh

At 76 years old, Bruce Cockburn is one of Canada’s most decorated musicians: 37 albums, 13 Junos and a recipient of the Order of Canada. As Cockburn makes his way around North America for his 50th anniversary tour (second attempt, due to covid), one of his encore songs may catch listeners by surprise. “When the Sun Goes Nova” was on and off set lists in the 70’s, and the off-beat song has only very recently made a comeback.

When I first heard the song as a 20-year-old, it seemed like a bit of lightheartedness in the midst of an otherwise serious and dark album (Night Vision, 1973). With an almost Vaudeville-show-tune feel, a youthful Cockburn sang: “If you’re on the bum / And the policemen come / If you lose your grip / Or your trousers rip / I’ll be waiting dear.”

It’s taken me most of the past 50 years to understand that the song is more than just comic relief. Cockburn is no longer a young folksinger; the gravity and tenor of his septuagenarian voice and our 2022 context of plague, war and environmental collapse gives these lyrics a profound new meaning.

"When the sun goes nova / And the world turns over / I don’t want to be alone / So honey come on home"

NIGHT VISION (1973)

There is something disquietly apocalyptic about this. When the sun that gives us our energy and our secure place in the universe, blows apart. When everything is turned on its head and you can’t find your bearings. You sure don’t want to be alone. In the midst of the chaos that renders us desperately homeless in creation, in society and deep within ourselves, we long for the safety and familiarity of home.

WAR AND CLIMATE CRISIS

In our post-truth world, it might be good to hear again the kind of dismantling that Cockburn accomplished in his 1985 song, “People See Through You”. While written in the context of Reagan era interventions in Central America, doesn’t this song resonate with the terror we are seeing in Ukraine these days? “You’ve got instant communication / Instant data tabulation / You got the forces of occupation / But you don’t get capitulation / ‘Cause people see through you” (World of Wonders).

Or how about the climate crisis? Isn’t it good to have someone remind us that:

"In this cold commodity culture / Where you lay your money down / It’s hard to even notice / That all this earth is hallowed ground / Harder still to feel it / Basic as a breath / Love is stronger than darkness / Love is stronger than death."

“THE GIFT,” BIG CIRCUMSTANCE (1988)

Don’t these tight eight lines capture both the heart of the problem, and the deepest resource of hope? We reduce the world to a commodity, forget that the earth is nothing less than the temple of God and become alienated from the love that is the very foundation of all creation.

Why should we seek a path of caring wisdom in the face of ecological insanity? Because love goes all the way down. In Cockburn’s imagination, the love that fires the sun calls forth love in response. “We’re given love and love must be returned / that’s all the bearings that you need to learn / see how the starwheel turns” (Joy Will Find a Way). Sounds like Psalm 19. Heck, it sounds like Jesus!

HYMNS OF LAMENT

In contrast to much superficial, sentimentally happy, Christian music, Cockburn knows the power of lament. He bears witness to the deep struggles of faith, doubt and disappointment.

In his 1996 song “The Whole Night Sky,” Cockburn offers words of empathy: “Derailed and desperate / Hanging from this high wire / By the tatters of my faith.” Listeners are invited to insert their own tragic loss or to think about times when they questioned everything about themselves, faith and God. “Sometimes a wind comes out of nowhere / And knocks you off your feet.” When you’re going through such a season, isn’t there some comfort, some sense of recognition, when you hear a contemporary psalmist describe your reality? “And look, see my tears / They fill the whole night sky” (Charity of Night).

But Cockburn is no “singer of songs without hope” (“Feast of Fools,” Further Adventures Of). Playing off the 13th century hymn “Stabat Mater” which sings of Mary’s sorrow bearing witness to Jesus on the cross, Cockburn’s 2016 song, “Stab at Matter” (Bone on Bone) situates the artist at the foot of the cross. But “Stab at Matter” takes an apocalyptic turn as the song bears witness to a world still hanging on that cross: “you got lamentation / you got dislocation / sirens wailing and the walls come down.”

Again, Cockburn does not avert his gaze or allow us to ignore the dissolution all around and deep within us. Walls of protection are crumbling and we are left defenceless. But there is hope in these falling walls. “You got transformation / thunder shaking / seal is broken and the spirit flies.” The world might be imploding and the false temples of our civic religion trembling, but somehow this is all a sign that “the Lord draws nigh.”

For good reason, apocalyptic imagery and eschatological hope intensifies during times of deep historical crisis, debilitating anxiety and cultural collapse. When it is all falling apart, when the story of your life and the life of your world seems to hit a dead end, all you can do is to “step out from the past and try to hold the line” while you are asking, “so how come history takes such a long, long time / when you’re waiting for a miracle” (“Waiting for a Miracle,” Waiting for a Miracle). And if you have eyes to see “just beyond the range of normal sight” you might catch a glimpse of Jesus in the fray of our history, “this glittering joker . . . dancing in the dragon’s jaws” (“Hills of Morning,” Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws).

THE JESUS TRAIN

Fifty years (and counting), Bruce Cockburn’s art continues to speak beautifully and powerfully into our 21st century realities. Recognized as one of the finest guitarists of our time, Cockburn’s fusion of folk, rock, reggae and jazz speaks into our malaise, as he bears witness to radical hope.

Throughout my adult life – my years as a campus chaplain, as a writer, scholar and professor – I have found Cockburn’s music to resonate deeply with scripture, and to be a faithful companion on the path of Christian discipleship. Some years ago, after Cockburn had written his memoir, Rumours of Glory, I asked him if he had written any new songs. “Yes,” he replied. “I’ve written something very ‘Christian’.” “Like, ‘how Christian?’” I asked. “Like ‘get on the Jesus train’ Christian,” he replied.

“Jesus Train” was released in 2017 on the Bone on Bone album. And while the motif of ‘trains’ has been ubiquitous in Cockburn’s body of work, this train has a clear destination. “I’m on a Jesus train . . . headed for the City of God.” The artist finds himself “standing on the platform / awed by the power.” He feels “the fire of love.” The love that fires the universe is somehow all around him, compelling, inviting, calling. He testifies, “feel the hand upon my shoulder saying ‘brother climb aboard’ / I’m on a Jesus train.” There is something wonderfully simple and direct about this. Cockburn knows all about “post-ironic postulating” (“Don’t Forget About Delight,” You’ve Never Seen Everything), his path has led through “dark places,” and sometimes the darkness was his friend (“Pacing the Cage,” Charity of Night). He has known “wounded streets and whispered prayers” (“Everywhere Dance,” You’ve Never Seen Everything), and he has been led beside “Strange Waters” (Charity of Night), but when it comes right down to it, he is on the Jesus Train, headed for the City of God.

So friends, have you found yourself “derailed and desperate”? Then Cockburn invites you to get back on track, to get on board the Jesus train. Maybe after all these years, Mr. Cockburn serves as a conductor on this train. It’s going home.

May 11, 2022

Colorado Springs Indy

MUSIC IN DANGEROUS TIMES

Singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn talks about Christianity and what he’s dropping from his setlist

by Bill Forman

When it comes to live shows, Bruce Cockburn has no shortage of songs to draw upon. There are the ‘80s hits like “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” and “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” the steady stream of albums that have followed in their wake (which have earned him ten Juno Awards in his native Canada), and a few unreleased songs he’ll be debuting on his current tour.

But one hit that Cockburn won’t be playing is “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” a song he wrote after visiting Guatemalan refugee camps back in 1984. It was Cockburn’s best-known hit in America, as well as his most controversial, with an accompanying video that depicted the genocide carried out against Indian villagers by the Guatemalan army, with whom the CIA happened to have close ties.

While MTV aired the music video frequently, radio programmers were less inclined to add the single to their playlists, not least because of its closing line: “If I had a rocket launcher, some son of a bitch would die.”

The song has long been a staple of Cockburn’s live shows, but that changed back in March when Russia fired more than 30 cruise missiles at a Ukrainian military base.

“I’d been playing it on all the U.S. dates, but stopped during the Canadian shows, because I just felt like it’s gone too far that way,” says Cockburn. “It’s always made me uncomfortable when people cheer for that song. And I don’t mean applause at the end of it because it was a good performance or something. But just when I sing the various lines — like even at the end of the first verse, ‘If I have a rocket launcher, I’d make somebody pay’ — and there’s invariably somebody — some male — in the audience that hollers out, ‘YEAAHHH!’ And I hate that, because that’s not what it’s about. And if they were thinking about what they were hearing, they would not do that. And I just didn’t want to play into that kind of sentiment in the current situation.

This isn’t the first time that Cockburn felt the need to give the song a rest. “The same thing happened after 9/11,” he says. “I didn’t sing it for a long time after that, because, you know, people were just looking for motivation to go out and do really bad things. Not that anybody in my immediate audience is likely to go do that, but it just was playing into the wrong part of the heart.”

While Cockburn has written numerous songs about human rights violations and third-world exploitation, he’s always done so with a poetic sensibility, and a depth of emotion, that sets him apart from more didactic political songwriters. He’s also a phenomenal guitarist, which is particularly evident on a pair of instrumental albums that prompted Acoustic Guitar magazine to place him on the same level as Django Reinhardt, Bill Frisell, and Mississippi John Hurt.While Cockburn has written numerous songs about human rights violations and third-world exploitation, he’s always done so with a poetic sensibility, and a depth of emotion, that sets him apart from more didactic political songwriters. He’s also a phenomenal guitarist, which is particularly evident on a pair of instrumental albums that prompted Acoustic Guitar magazine to place him on the same level as Django Reinhardt, Bill Frisell, and Mississippi John Hurt.

“When I was learning to fingerpick, I did my best to emulate Mississippi John Hurt and Mance Lipscomb, and some other guys like that,” says Cockburn. “Brownie McGhee was also an influence. I saw Brownie and Sonny [Terry] play dozens of times at this club in Ottawa that I hung out at on a regular basis. Well, probably it wasn’t dozens of times, but it might have been, because they’d come a couple of times a year. I love that music, and it’s still part of what I do.”

Cockburn was 14 years old when he found the dusty old guitar in his grandmother’s attic that would put him on the path to a life in music. Another pivotal moment, he says, was dropping out of Berklee College of Music.

“I was headed toward a bachelor’s degree in music, which would have entitled me to teach music in high schools, which I had no interest whatsoever in doing,” he says. “I was interested in the content of what was being taught, but not in terms of using it as a teaching career. And then I reached the point where I had this realization, ‘I gotta get out of here, this is not where I’m supposed to be.’ And I listened to that, and I acted on it.”

The other primary influence on Cockburn’s life has been his spiritual beliefs, which find their way into his lyrics without hitting you over the head with them.

“I think my relationship with God is the most important thing in my life, and the one I sort of struggle with the most probably too,” he says. “I wasn’t plugged into a community for a very long time, but through a combination of circumstances in San Francisco, I started going to church again after having not done it for maybe 30 years, 40 years. It was a small, non-denominational church with all these really accepting and loving people. The congregation was racially mixed — you know, people from all sorts of Asian extraction, African-Americans, white Texans, and Samoans — all kinds of different cultures mixed there. And it was accepting of gays and, you know, whatever else — people that feel, as I do, that their relationship with God is of paramount importance.

“When I showed up, they didn’t know who I was. I was just the old guy with an attractive wife, who’d discovered the church before I did, and eventually persuaded me to go. Then they found out I played guitar, and I ended up sitting in with the band and becoming more or less their guitarist. But then COVID, of course, killed that. So new things have happened since, but there was definitely a sense of community.”

All of which is a far cry from the divisive preachings — or, as Cockburn puts it, the vile bullshit — that comes out of the religious right.

“If you start using the Christian faith as a reason to hate people, it’s completely antithetical to what it’s about,” he says. ”And yet, historically, of course, it has been used for that over and over again.

“But, you know, I don’t think anybody who pays attention to what I have to say is gonna confuse me with that other stuff. The challenge, of course, is will they listen to what I have to say, or just write me off? Either way, I’m not gonna stop calling myself a Christian. And if you can’t deal with it, well, that’s your problem.”

April 27, 2022

A Journal of Musical Things

Photos from Bruce Cockburn’s 50th-anniversary tour and his Canada’s of Walk of Fame Star

by Ross MacDonald

It is not often that a concert starts with a standing ovation; however, that is exactly how Bruce Cockburn‘s show at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa started off. But then again, Bruce Cockburn is folk/rock royalty, with over 50 years as a professional musician, countless album sales, 13 Juno awards, and being a major influence to many of today’s folk and rock guitarists. And Bruce has been much more than that, as an environmental activist and proponent for the rights of farmers and indigenous peoples throughout the world; notably Oxfam (famine and poverty relief) and SeedChange (formerly USC Canada: farmer and human rights advocacy).

As Bruce began the evening, he joked that this is his second attempt at starting his 50th-anniversary tour (there have been a lot of re-starts to touring around the world the last couple of years). He released his debut self-titled album in 1970. He also spoke about how in his youth going to summer camp in Algonquin Park, spending a great deal of time canoeing, which he said was synonymous with nature.

The concert started with an instrumental ‘Sweetness And Light’, off his latest 2019 album Crowing Ignites. The song had riffs that harkened back to some of his music from the 70’s. It was a stripped-down evening with just Bruce alone on stage with his acoustic guitar (except for one song with lap steel guitar), and on some songs playing chimes with his foot.

But Bruce put on a spectacular show of his craft, simultaneously picking and strumming his guitar, stretching out his fingers on the fret-board playing bass and high notes at the same time. And his voice hasn’t changed, powerfully hitting all the high notes in all his songs. The fans showed love for Bruce’s new singles, but were especially ecstatic to hear long-time favourites ‘If A Tree Falls’, ‘Lovers In A Dangerous Time’, and everyone was singing along to ‘Wondering Where The Lions Are’. And of course, the evening closed with an even longer standing ovation.

On Monday 25 April, the National Arts Centre hosted a special event for Bruce Cockburn. In November 2021 Canada’s Walk of Fame inducted Bruce, along with ten other prominent Canadians. Unfortunately, it was a virtual ceremony due to the COVID pandemic. So the Walk of Fame took the opportunity to honour Bruce with a Hometown Star in his home town of Ottawa.

Bruce was joined at the ceremony by his family and long-time friend, manager, and founder of True North Records, Bernie Finkelstein. Also in attendance was another Ottawa music icon Sneezy Waters. As part of Bruce’s induction, the Walk of Fame will be making donations to SeedChange and Unison Fund (counselling and emergency relief services to the Canadian music industry) on Bruce’s behalf.

At the ceremony, up and coming First Nations singer-songwriter Mary Bryton Nahwegahbow sang the national anthem in English, French, and Anishinaabemowin. She later sang ‘Lovers In A Dangerous Time’, no easy feat in front of the iconic Bruce Cockburn, who seemed moved by her beautiful rendition.

Canada’s Walk of Fame is in Toronto, but Bruce’s Hometown Star plaque will be mounted at 521 Sussex Drive, where Le Hibou Coffee House once stood, Ottawa’s unofficial headquarters of performing arts in the 1960-70’s where Bruce started his career. A fitting tribute to one of Canada’s greatest troubadours.

More on this event at Bruce's official website.

April 25, 2022

Ottawa Citizen

Bruce Cockburn honoured with Walk of Fame star in his hometown

by Blair Crawford

When Bruce Cockburn was asked where he wanted his hometown star from Canada’s Walk of Fame to be placed, he chose the site of Le Hibou coffee house.

“I was asked what places matter the most to me in Ottawa and Le Hibou was what came to mind,” Cockburn said at Monday’s unveiling ceremony at the National Arts Centre.

The NAC is where Cockburn played a sold-out concert Saturday night. It’s also only a few hundred metres from where Le Hibou, the city’s legendary hippie hangout, once stood on Sussex Drive.

“It was such a nexus for all kinds of creative energy in this town,” said Cockburn, 76. “It’s where I learned how to do what I do.”

What he did over the next 52 years was win 13 Juno Awards and the Order of Canada and earn plaudits as one of the world’s virtuoso guitar players. His humanitarian work includes campaigning for Indigenous rights and a ban on land mines, as well as advocacy work with Oxfam, Friends of the Earth, Amnesty International and Doctors Without Borders.

The award comes with a $10,000 charitable donation, which Cockburn directed to the Unison Fund, an organization that supports young musicians, and SeedChange, the current incarnation of the Unitarian Service Committee, with which Cockburn has long been associated.

“Ottawa, growing up, seemed like a good place to get out of,” he joked, “but I think everyone thinks that of where they grew up. At some point you have to leave your roots behind.

“But at this point, it just feels really good to be back here.”

Editor’s note: Bruce Cockburn’s star on Canada’s Walk of Fame will be placed at the site of the former Le Hibou coffee house on Sussex Drive. Also, the name of the charity he’s supporting is SeedChange. Incorrect information appeared in a previous version of this story.

Photo: Jean Levac

April 25, 2022

CTV News Ottawa

Bruce Cockburn honoured in his hometown

by Dave Charbonneau

For more than five decades, Ottawa’s Bruce Cockburn has been writing and performing hit songs, and now, he’s been honoured in the capital.

Cockburn was awarded with a Hometown Star following his recent induction into Canada’s Walk of Fame. He says this award is special.

“This was comfortingly informal and casual, and yet substantial too,” says Cockburn. “So I guess, of the two, I prefer this thing, if we had to take one or the other.”

Dozens of friends, family and fans were in attendance at the National Arts Centre to celebrate Cockburn’s achievements.

“We have transformed Canada’s Walk of Fame to mean more, to more people, more often,” says Canada’s Walk of Fame CEO Jeffrey Latimer. “And our hometown visits also include a placement of a permanent plaque displayed in a location of our inductees’ choice. Something that was significant to them.”

Cockburn's songs truly represent the voice of his generation. Songs like Lovers in a Dangerous Time, which was covered by fellow Canadian band, The Barenaked Ladies.

He's won 13 Juno awards and is an Officer of the Order of Canada.

“You know, it’s great to see Bruce in his hometown, just getting close again. I like that,” says Cockburn’s manager and long-time friend, Bernie Finkelstein. “Not that it was apart, but just, it’s nice. I just think on a human level it’s nice.”

The plaque will most likely be placed on the wall outside what used to be Le Hibou Coffee House on Sussex Drive, where Cockburn, as well as many famous Canadian musicians frequently played in the 1960’s and 70’s.

“One of the things that is great about Canada in my mind, is our willingness to celebrate each other,” says Cockburn. “And it feels really good to be part of that.”

This honour comes with $10,000 charitable donation. Cockburn, the humanitarian, is glad to help. Giving half to SeedChange and the other half to the Unison Fund.

“One of the greatest things about it is the ten thousand dollars that I get to divert to a charity of my choice,” says Cockburn.

The world knows about Bruce Cockburn, his music and his compassion. Now his hometown can recognize his impact forever.

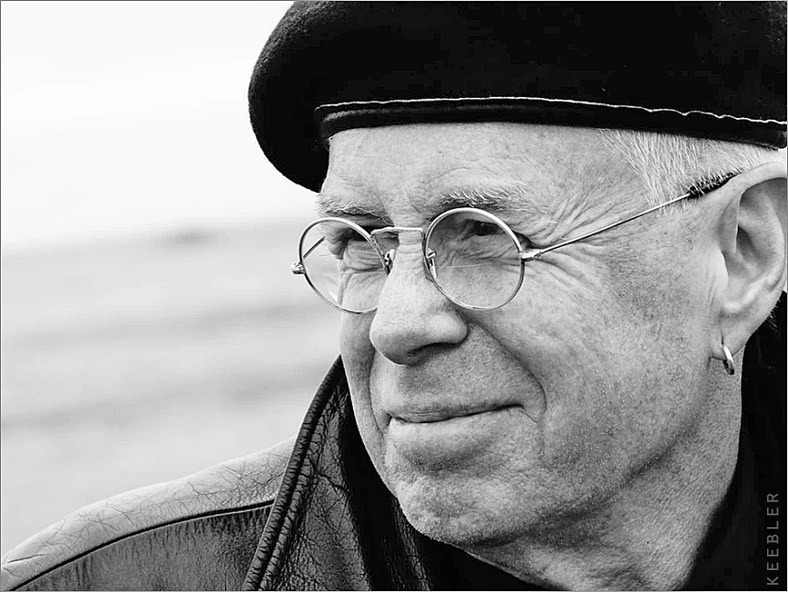

First photo: Dave Charbonneau - Second photo: Sean Kilpatrick

April 22, 2022

Ottawa Citizen

Bruce Cockburn reflects on his Ottawa roots: "I look back with fondness"

by Lynn Saxberg

Bruce Cockburn is back in hometown Ottawa for a few days, primarily to perform a solo concert at the National Arts Centre on Saturday.

While he’s in town, the legendary singer-songwriter-guitarist will be honoured during a ceremony at the NAC on Monday marking his recent inclusion on Canada’s Walk of Fame. Though he says he’s always been ambivalent about fame, the recognition is sweet.

“I do feel like I’ve contributed something to Canadian life over all these years so it feels nice,” the 76-year-old said in a wide-ranging interview that also touched on growing up in Ottawa, his political awakening and the crowd reaction that’s making him increasingly uncomfortable.

Here’s more from the conversation, lightly edited for length:

Q: You’re on tour after a long stretch of pandemic-related shutdowns. What’s that like?

A: When we started in December, there was a tentative element around it like nobody was too sure there wasn’t going to be some major interruption. But on the other side of that coin, the audience vibe is fantastic because you’ve got a bunch of people in a room looking at each other going, ‘Holy jeez, we’ve got a bunch of people in a room, and we’re not quaking with fear.’ People are just really glad to be out at an event, I think.

Q: The tour celebrates the 50th anniversary of your first solo album in 1970. Where were you when it came out?

A: I was living in Toronto. I remember the day the album came out, it got sent to CHUM FM, which was this new freeform FM radio that everybody was listening to. They got hold of the album and played the whole thing from beginning to end, and every time I went into a store in Yorkville, I could hear my friggin’ voice coming at me, and it scared the bejeebers out of me. I thought I’d never have privacy again. It was completely in my own head. No one in the store knew what I looked like, but it was a terrifying feeling. I had this vision of the future that was quite dark. And then, of course, it turned out to be correct in a way, but not at all dark.

Q: How do you think growing up in Ottawa influenced your musical path?

A: It’s hard to pin down a specific element, but where it starts to matter is the middle of high school when I was playing enough guitar that I could actually do it in front of people and not be embarrassed. In Grade 11, I was in a class with Peter Hodgson (later known as Sneezy Waters) and he was another guy who played folk guitar. Peter and I got chummy right away with guitars and he introduced me to Sandy Crawley and the three of us spent a lot of time playing and listening to music. Then he introduced me to the scene around Le Hibou, and it took off from there.

Q: What was that scene like?

A: It was really seminal for me. I wasn’t writing songs yet, or I hadn’t tried to really, but we were appreciating songwriting in the folk world, as well as the pop world, like the Beatles and Stones. We were excited by that stuff, and still thought of ourselves as folkies. Then I went away to Boston to go to school and came back and joined The Children, and it went on from there. I think the Ottawa scene benefitted from a very fertile atmosphere and it was less competitive than Toronto or Montreal. It was a good place to learn your craft. I look back with fondness on that.

Q: People say that growing up in the nation’s capital gives one a political awareness, too. Was that the case for you?

A: I was aware of what was going on in the world around me, but I think it had more to do with my parents. We didn’t listen to the news religiously or have discussions of world affairs around the dining table, although we did sometimes. I kind of grew up with a degree of concern for people’s wellbeing but I was not very politically engaged in that era.

Q: When did that change?

A: It wasn’t until I started traveling west in Canada in the ’70s. That’s when I started meeting Indigenous people, and it was a real eye opener for me. I was a new Christian in those days and there was all these abuses that had been committed in the name of Jesus and the church. I was horrified by that, and it shows up in some of the songs from that era, and it went on from there, expanded to other countries and other situations.

Q: One of your most hard-hitting songs is If I Had A Rocket Launcher. Are you playing it these days?

A: I have been playing it in the shows but I’m wrestling with it a little bit right now actually. I stand by the song, and it fits to some extent what’s going on in Ukraine, although I certainly wasn’t thinking of Ukraine when I wrote it. What bothers me is when people cheer. They cheer the chorus, and especially the last line of the song. It’s never a whole audience that does that, it’s always one or two voices. It gives me the creeps every time because it’s somebody celebrating the horror. They don’t mean it that way but that’s what they’re doing. So I don’t know if I’ll keep singing it or not.

April 18, 2022

The Record (Kitchener, ON)

For Bruce Cockburn, 50 years of songwriting and performing ‘is an incredible gift’

by Terry Pender

Bruce Cockburn is writing new songs, touring and making plans to record his 38th album. For Canadian folk-rock legend Bruce Cockburn the songwriting gets harder but he’s still finding the words and music after more than 50 years.

Twice delayed because of the COVID pandemic, Cockburn plays Centre in the Square April 21 as part of a 50th anniversary tour. “It feels really good to be back out working after a couple of years of not,” said Cockburn. “It does feel kind of noteworthy. It is half a century, it is fun to be out and be able to celebrate that.”

Soft-spoken and humble, the 76-year-old could not stop writing and performing even if he wanted to.

He certainly doesn’t have to keep at it, after winning 13 Juno Awards, an induction into both the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame, the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award and being made an Officer of the Order of Canada

“The motivation is the same as it was in the beginning: there is an urge to put feelings and thoughts on paper and make them into songs. And an ongoing urge to play the guitar,” said Cockburn.

His first album was released in 1970, and he was shocked to hear a new station called CHUM FM play the whole thing. These days he’s shocked at how little Spotify and others streaming services pay musicians, but that’s another conversation.

“It’s still what I do,” said Cockburn. “The ideas are harder to come by. How many ideas do you have in your life that are worth sharing with people? It becomes harder to avoid repetition as time goes on, but the motivation is just as strong.”

A few months ago he released “Bruce Cockburn’s Greatest Hits, 1970-2020.” “Most of the songs were not really hits, we wish they were hits,” he said, laughing. He personally selected the tracks for the double CD, including fan favourites from live shows, the ones he likes most and the hits from his 37 albums.

“If you are around long enough, you become an icon,” said Cockburn, chuckling. “It is not something I ever aspired to, it is just as result of doing what I love and having people interested in it for long enough.”

Raised in Ottawa, Cockburn started playing guitar in high school and performing at a coffee house called Le Hibou during the 1960s. It was part of a folk circuit that brought a young Cockburn to Toronto and London, Ont., where he played SmalesPace in the 1970s.

“The first time I played that club I slept on the table overnight,” said Cockburn of SmalesPace.

A routine day for Cockburn is focused on his 10-year-old daughter Iona and his wife MJ. They live in San Francisco, where he has lived for the past 13 years. Cockburn rises at 6:30 a.m., prepares breakfast and drives his daughter to school for 8:30 a.m.. He also picks her up at the end of classes every day.

In between, he plays and practises the guitar and works on new material. He is playing some new songs on this tour. He reads a lot, including science fiction and poetry. For him, authors provide more inspiration than other songwriters.

He always starts a song by writing the words first. The music comes later. He listens to jazz, classical and world music for inspiration. “Something like a lyric of a song develops and when there are enough words to see the shape of it, I start looking for music for it,” said Cockburn. “It is basically hunting around on the guitar to find the right style of music for the lyrics.” he said.

He’s written about 300 songs in his career. The fastest one came together was in an hour or two. The longest one took 37 years. “ ‘Celestial Horses’ is the name of that song and I wrote the lyrics in the mid-’70s,” said Cockburn. “It never quite jelled. I really liked the verses, but I could never quite make it work.” Then one morning when he was living in Montreal the idea for a chorus “came out of nowhere.” “And the song got finished,” said Cockburn, and it was released in 2003 on his album “You’ve Never Seen Everything.”

Cockburn and his family spent most of July 2021 on vacation in Hawaii. He wrote many new songs there.

“The first one of those just kind of popped out. I was up, it was early in the morning and nobody else was up, and I am looking at the landscape. And the idea for the song came, and it was done by the time everybody was having breakfast,” said Cockburn.

“Once in a while that happens. It is a gift I feel when that happens,” he added.

The song is called “Into the Now,” and he performs it on this tour. “Into the Now” will be on his next CD. There are tentative plans to record this fall.

In the 1980s Cockburn had a place in Toronto near College and Clinton streets, then he lived on nearby farms before moving back to the city. His last Toronto home was near St. Clair Avenue and Dufferin Street.

“I woke up one day and it was 2000 and I had lived in Toronto for 20 years, and it was time to move, so I moved to Montreal,” said Cockburn.

After a few years, he moved to the Kingston area where he met MJ. They lived in Brooklyn for a brief period of time, and then moved to San Francisco. They rented a place for years in the Cole Valley neighbourhood, and recently bought a home in the Bernal Heights neighbourhood.

“We are here because my wife got a job here, and she was living here when we first started going out,” said Cockburn.

But he likes it, calling San Francisco quirky, interesting and beautiful. “I am really enjoying the experience of living on the West Coast. I never imagined I would be a West Coaster,” he said. “It is pretty great.”

These days, profound gratitude is his dominant emotion.

“To still be alive at 76 and still functioning and to have been able to do all this stuff for so long, it is an incredible gift and one for which I am very thankful,” said Cockburn.

April 17, 2022

Peterborough Examiner

Bruce Cockburn reflects on career ahead of Peterborough show

by Brendan Burke

Acclaimed singer-songwriter and Canadian music icon Bruce Cockburn is many things.

A skilled guitarist. A natural wordsmith and prolific lyricist. An experimenter of folk, rock, pop and jazz. A spiritually minded creative.

But if you ask the Ottawa-raised performer, he’ll likely tell you he’s merely a vessel: a man with a guitar trying his best to convey the human experience one melody at a time.

“An artist’s job is to distill what you can grasp from life into some communicable form and then share it with people; and life includes all of these different things: sex and politics and violence and love and the divine,” Cockburn said in a recent interview.

“I mean, it’s all in there, so why not sing about it?”

Now marking 50-plus years in the industry with an anniversary tour in Canada and the U.S. — including a stop at Peterborough’s Showplace Performance Centre on Tuesday — Cockburn is reflecting on his decades of work and his celebrated catalogue.

It all started with an old guitar.

At the age of 14, Cockburn discovered the stringed instrument in his grandmother’s attic.

He was transfixed.

Already enamoured with early rock and roll, the avid sci-fi reader and lover of poetry put down his clarinet and picked up the guitar.

“I understood that whatever my life was going to be about, it was going to revolve heavily around the guitar,” Cockburn said.

His parents supported his dreams — with a few conditions: take lessons and don’t grow sideburns or wear a leather jacket.

“I didn’t know if I had a knack for it or not. I just knew I wanted to do it and, in taking lessons, I progressed. By the end of high school, there was nothing else I wanted to do with my life except play guitar,” Cockburn recalled.

Immersing himself in his early musical influences — from Bob Dylan and the Beatles to Mississippi John Hurt, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry — Cockburn went on to join a string of bands in Ottawa and later Toronto before releasing his debut self-titled album in 1970 — marking the beginning of his illustrious, genre-bending career.

He went on to release a slew of albums that decade — continuing to explore themes of spirituality while shifting to politically-charged songwriting and a fuller sound with tracks like “It’s Going Down Slow” on his third album, Sunwheel Dance — culminating in the watershed 1979 album “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws.” The album featured Cockburn’s breakthrough song “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” which saw his popularity surge south of the border.

“I never thought of what I do as a career and I’ve never made plans around it. So when something like that comes along, I’m grateful for it, but it’s not like ‘finally, I’ve got to where I needed to go.’” I just never think about it.”

With the release of “Stealing Fire” in 1984, Cockburn put out two of his most beloved and well-known songs, “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” and the politically driven “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.”

Cockburn recalls having second thoughts about releasing Rocket Launcher, a track he penned after being shaken by the turmoil faced by Guatemalan refugees in southern Mexico.

“I thought it would be misunderstood. I thought people would hear it as something that was an incitement to violence and I didn’t want to put that out.”

But Cockburn understands the lasting impact of the song — despite “never being that interested in protest songs” — and how music is interpreted with the passing of time.

“When I sing it now, I know people are hearing it in light of what’s going on in Ukraine. I don’t want to promote that kind of feeling particularly although I feel it too,” Cockburn said.

“What’s going on there is horrible and it should never have happened and the people responsible for it should be held to account. But we’ve got to get over the knee-jerk response that goes with violence and we have to get off that train somehow.”

Looking back, Cockburn says his exploration and progression as an artist has allowed him to avoid being placed in a genre-specific box.

“People would say, ‘oh yeah, he’s a Christian singer, oh yeah, he’s a political singer, and then after a while I think most people have given up now because they don’t know what to call me because it’s all over the place.”

Peterborough concertgoers attending Cockburn’s 50th anniversary tour can expect a mix of fan-favourite staples and newer material, including tracks from his 2019 instrumental album, “Crowing Ignites.”

As for what’s next for Cockburn, he already has close to an album’s worth of new songs that he hopes to record soon.

“I don’t take it for granted. I don’t assume that the ideas are going to keep coming. But as long as they do, I hope I can keep on making use of them.”

April 14, 2022

Belleville Intelligencer

Bruce Cockburn on his long career, spiritual songs, and new tour

by Luke Hendry

Singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn is feeling reflective.

That may not be surprising, given his more than 50 years in music and the recent release of a greatest-hits album.

He still has plenty of music in him, and, in an Intelligencer telephone interview, said he’s eager to share it with audiences.

On April 26, Cockburn will be back on Belleville’s Empire Theatre stage for a solo show, part of a pandemic-delayed “Second Attempt” 50th-anniversary tour of Canada and the United States.

Speaking from San Francisco, where he’s lived for years, the Ottawa native said tour audiences will hear one or two of his new songs.

In choosing older tracks for his Greatest Hits 1970-2020 album, he said, “we made it easy on ourselves” and simply compiled his singles.

“Not all of them were hits,” he said.

Cockburn said the album would not be “that commercially-viable” if he’d chosen his favourite tracks. But he’d already done that, in a way, with the box-set released in 2014 with his autobiography; both are named Rumours of Glory.

Spiritual leaning

His songs with “some sort of spiritual relevance” are his current favourites.

“That idea I like very much.

“The general thrust of the new songs is kind of more spiritual.”

Cockburn said that is a generalization, but the new work does “lean that way.” Sales of his “Four New Songs” collection benefit his church, San Francisco Lighthouse, and Lighthouse Kathmandu, a Nepali organization targeting human trafficking and rescuing victims.

“It’s sort of a cliché of the adult life: that you start off exploring and you go through all these various stages … and you end up attempting to be a sage or something.

“My life’s kind of finding an arc like that.

“There’s room for political opinions and stuff like that but … a more reflective angle is where I find myself seeing things from.”

The writer of “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” “Lovers in Dangerous Time” and many more has used his music to express his views, as he did with “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” and other songs.

“I don’t know what I would write about war at this point,” said Cockburn, explaining he’s already done that several times.

In the case of “Rocket Launcher,” “I wrote it because I had to because I had a feeling in my gut and my heart.”

In talking about political events, Cockburn said, “I’m not hopeful, particularly. I have hope in me, personally … but I think we’re in trouble, for many reasons.”

“Climate change will cause further tension and disruptions beyond those of the pandemic," he said.

Cockburn said two of his four newest songs – “Orders” and “Us All” – speak to the need to and deal with disagreements “in a civil way, instead of what’s tended to be happening” in the world.

“The message that we need to love everybody … People might get tired of hearing it, but I think we need to hear it over and over again right now.”

Music “explosion”

Cockburn had booked about 100 shows prior to the pandemic and cancelling them was disappointing, he said.

About six months into the pandemic, he and his family rented an RV and went on a different kind of tour, parking at friends’ homes and having safe visits on the lawns. The trip included a jam with violinist and former collaborator, Jenny Scheinman.

“Neither Jenny nor I had played with anyone for months.

“This kind of explosion happened. It felt like a kind of emotional explosion because we were able to do this.

“Some of the live shows have kind of that feel.

“The sense of novelty and the sort of rediscovery to sit in a room with people and feel good, instead of scared or whatever, is pretty great.”

Practises regularly

Pandemic or otherwise, Cockburn does not, however, neglect his playing and writing when he isn’t touring.

“I practise all the time, and if I don’t, I pay a price for that,” he said. A break feels good, he said, but playing the guitar is “like any other physical exercise” and a few days away from it may mean he needs a week to get back into form.

At age 76, he said, regular practice keeps his muscles from stiffening.

Cockburn said the pandemic didn’t change his writing or the frequency of his practising.

“The pace of my writing is about the same,” he said. “It’s always been just a wait for the good idea.”

He said some of his new songs arose from the “atmosphere” of the pandemic and current events.

“One song (“When You Arrive”) actually mentions COVID, but it’s not a song about COVID.”

Taking notes

Cockburn isn’t the only one ensuring he stays sharp. Iona, who’s 10 and the youngest of his two daughters, may enjoy today’s pop hits but she also knows her dad’s catalogue. She’s studying guitar and piano and learns songs rapidly despite little practising, he said.

“She’s toured with me since she was two months old and loves being on the tour bus.”

“Iona’s got all these notes” she makes at his sound checks, but he’s not sure of her plans for them.